by Derek Neal

“Paradiso” by Erlend Oye is a song I’ve heard many times in many different settings. This is largely a result of circumstance: it is one of the few songs I keep on my iPhone, and I return to it when I’m driving and my phone doesn’t have cellular service. Once upon a time I had an iPod loaded with an extensive music library, thousands and thousands of songs, maybe even up to and over 50 GB, although I suppose this number has steadily increased in direct relation to the time it’s been since I owned an iPod. Every generation has their version of this story—record collections, cassette collections, CD collections, MP3 collections. Perhaps my generation was the last to experience the phenomenon of collecting and curating a music library as an ordinary cultural experience and not as a conscious act of rebellion against streaming technology, which by its very nature precludes the idea of ownership, having or not having, and the decisions that lie therein.

“Paradiso” by Erlend Oye is a song I’ve heard many times in many different settings. This is largely a result of circumstance: it is one of the few songs I keep on my iPhone, and I return to it when I’m driving and my phone doesn’t have cellular service. Once upon a time I had an iPod loaded with an extensive music library, thousands and thousands of songs, maybe even up to and over 50 GB, although I suppose this number has steadily increased in direct relation to the time it’s been since I owned an iPod. Every generation has their version of this story—record collections, cassette collections, CD collections, MP3 collections. Perhaps my generation was the last to experience the phenomenon of collecting and curating a music library as an ordinary cultural experience and not as a conscious act of rebellion against streaming technology, which by its very nature precludes the idea of ownership, having or not having, and the decisions that lie therein.

I could be wrong: maybe kids today sit on the school bus and share their Spotify libraries with each other in the same way that we would hand over our iPods and await judgement. But without the need to own music to listen to it, to decide what’s in and what’s out, and when everyone has access to every song, there must naturally be less of an impulse to cultivate a library. In any case, I’ve often found myself in various locations where I can’t stream Spotify, or call up YouTube, or listen to a DJ mix on SoundCloud: for example, driving in a foreign country, or going to my family’s cottage where the reception is poor, or when I simply don’t have any data left on my phone. “Paradiso” is one of the songs that I’ve returned to in these moments, and it has wormed its way through my ears and into my brain, not from love or obsession, although I do of course enjoy the song, but from mere repetition and necessity. The song describes one of the eternal human dramas that everyone will be able to relate to at some point in their lives. Read more »

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor. Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch  I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

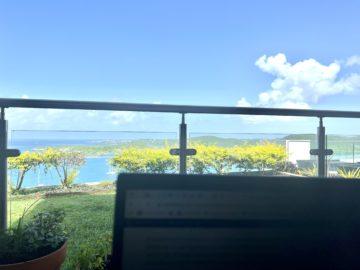

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.