In memory of Joe Blades, Broken Jaw Press embodied

by Eric Miller

Copse and cosmos

Copse and cosmos

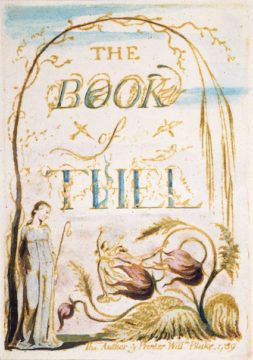

Do you find that, even while garden-seated—garden-stirring—, you yearn after gardens? Or that, once you have gotten in, you dapple the place with other spots and then, like a mirage, abide in the very measure in which you cease to be? This is more than solitude’s swing, or Fragonard’s for that matter. Then, across the clearing—the clustering scuff, blur and spin of amenities, where even boulders flock, ruffle and (foliaceous) flutter—, planes in view dovish a work over which I bent a shadow, juvenile. I did not know any of the story of the story, I only tried looking. It said “The Book of Thel,” and weighed less than a sandal might. My saltatory eyes spanned phrases and figures, a treehopper, painless impingement, clicks, thorn-shaped, as it springs. That kind (Family Membracidae) is all there once it gets there but most it leaves out, with integrity jumping to inconclusions. Nature does make leaps. I mean, in no time. The author? William Blake, whom plenty consider out of date because he was born some while since which is reckoned a fatal shortcoming in many respects and whom others still enjoy and these latter extenuate their suspect pleasure as resourcefully as they can.

I don’t care what the opinion is, opinion is blather, a sort of breeze fitfully brisk and smoggy, I don’t care except about how the book lives in me not otherwise than I live, sometimes living in gardens for a time. In this sense I am Blake’s ideal reader because I am not reading Blake, he doesn’t matter, here are certain verses and truths of ultimately unknown make and these are like dreams in part recalled. In Van Dusen Gardens, as in all gardens, there are intimate places, more intimate than I am to myself, experiences more than memories I never had that I can occupy and vacate like a nest box, and in those places today I see Thel passing, her high-waisted dress.

How many have died before us. Blake taught me I am a body and should not let other bodies, who have no more and no less authority than mine does, this being true destined democracy esoteric yet animal, expropriate from me the images that proceed from this, my body not yours. All you see is owing to your metaphysics is a motto Blake inscribed on a sundial in a garden of my mind’s invention, that is don’t let others tell you you are what they see unless it is what you are your body. It is not “passive” resistance an impossible idea in any case.

What anyone sees and what anyone says tells you about them and that is useful and is even their poetry and recall that poetry comes in a great many kinds and also, you have the choice not to bother with it. Or you can anthologize it a pretty project. You can smile for years over the quainter efforts, that happens in a garden too, Et in Arcadia ego—ridiculous ego I’d say, would you look at this latest script. Let’s stage it here, beside the grotto of the nymphs. Many an Alice never gets through the looking glass. Is that good or bad? In this installment Ulysses must escape Psy-Ops, not Cyclops. “Copse” is an English word for underwood. New part is, some on the left. Ulysses is wily what else? He knew about the covert over on the right, and he can’t help it, maybe he’s a sentimentalist, he does not admire but he likes this other, unfamiliar, shabby young plant anyway. All the cowardice of its convictions on the go! Pity is like light. Falls differently as you age, he is old enough to understand what does not understand itself, it has not the distance, it thinks it can outflank the moment. Nope. Wait a while, and see.

Now shut your eyes. The garden is there whether we are or not, sure proofs not of an afterlife but of something of that kind alongside us substantial as a friend farouche, fey, one of those unscripted un-ordinaries you can’t believe you witness all because at the moment you don’t have a point of view. Put down the script. Put down your point of view.

Don’t lounge in a garden is tyranny and don’t listen to it. They usually kind of want you out of it so they can get at you, you know siblings. I was never an only child. That teaches you as much as Blake.

Why are eyelids stored with arrows ready drawn?

Blake’s “Book” takes seven-beat slow steps, heptameter. Important, otherwise the long-legged glamour would come short. The heroine of the poem is Thel, a creature like and unlike a young woman. She dwells in the Vales of Har, she has siblings and I am sure they—and possibly you—would find her too much. She moans in her ravine in this way, a sort of Princess Hamlet,

Ah! Thel is like a watery bow, and like a parting cloud.

Like a reflection in a glass. Like shadows in the water.

Like dreams of infants, like a smile upon an infant’s face.

Like the dove’s voice, like transient day, like music in the air:

Ah! gentle may I lay me down, and gentle rest my head.

And gentle sleep the sleep of death.

Thel scatters similitudes, and retrieves every one for herself—prismatic, glassy, aqueous, infantine, columbine, melodious. She wants to remain the centre of this diffusion yet die gently in it. I have been like that. The wish is hardy, “perennial” is the term of art. The gardens of Adonis last but a day. Yet Blake knows as everyone might know that this desire is irresponsible, in the root sense of that word. The cosmos always responds in its measure, this is not a mystical but a matter-of-fact thing to say. We invoke powers, either being answerable for them we speak with them: or, maybe defaulting, maybe incapable, we do not, we cannot.

These are powers a crowd can never help us with and powers a crowd cannot, either, impose on us. Every crowd, including the ones I join when I join a crowd, dislikes them heartily, heartily. For they are free—the freest in existence. And they can kill us if we ignore them, kill us one way or another. Be careful then. A crowd too can kill us, that is another sort of death. It batters us with images at the very least, so much is a commonplace nowadays and has been for the longest time. What mere strangers kill is, however, only what they can see, and metaphysics differ as bodies in time do. Nothing is identical. In this sense not a person in the world has ever been killed, Cain need not have been marked or the mark was, precisely, his idea of his act of murder and just that. Talk to Abel about it. Let a crowd kill you then, there is an awful lot of unkindness everywhere you look, don’t lie about that, some dying is propitious, powers can revive you only once you need revival.

In other words it turns out the similitudes Thel lists so fluently and so casually each summon against her expectation a garden life to talk with her. Likenesses are untenable, behold the consequence of your incantation: you are a visionary and try listening, we live in a garden of unlikeness, it is in fact hard to die. First of the apparitions comes to converse with Thel that Maytime flower the Lily of the Valley, absurdly virginal as we—that is to say, Thel—are. Thel asked for the flower is the point here, she said it was like her, but she thought she was not asking, she was just mentioning. But you can’t get away with that.

And Thel will not be consoled by her affinities with this talkative small thing that loves lowliness even though Thel said she loved lowliness and was like a Lily of the Valley, and she recoils from the Lily, the first of the powers to offer her conversation. With the following words (referring to herself, as is her custom, by name in third person style), she appeals now to the tall aether instead of the watery hollows where valley lilies thrive:

But Thel is like a faint cloud kindled at the rising sun:

I vanish from my pearly throne, and who shall find my place.

Let Blake himself explain some more,

Queen of the vales the Lily answered, ask the tender cloud,

And it shall tell thee why it glitters in the morning sky.

And why it scatters its bright beauty through the humid air.

Descend O little cloud, and hover before the eyes of Thel.

And so, to abridge all too brusquely a most extraordinary tale, likeness after likeness which Thel has tried to fix speechless in place as her adjunct shifts from stuck similitude to its own processive incarnation. Rejecting (as you might have guessed) the Cloud’s counsel, Thel protests that, unlike him, she lives only “to be at death the food of worms.” Not hard by now to anticipate the identity of her next acquaintance, “The helpless worm arose.” Encountering the Worm leads Thel to the elemental, parental Clay, and the Clay speaks, the very earth, and invites Thel to see her own grave and Thel hears the last voice of her book, questions not answers,

Why cannot the ear be closed to its own destruction?

Or the glistening eye to the poison of a smile?

Why are eyelids stored with arrows ready drawn,

Where a thousand fighting men in ambush lie?

Or an eye of gifts and graces, showering fruits and coined gold?

I leave those inquiries with you. As always in William Blake, who is certainly old-fashioned, you will see his illustrations tell a story distinct from his poem’s.

Happy the heart that knows the causes of things

Dear reader, why ask me out of the blue (such heavenly blue, today), Do you believe in cause and effect?

Friend, a touch more precision would be nice. Clarify. What sort of cause and effect? As Linnaeus prompts us to recall, the kind of anything had better be specified. Would you happen to mean retaliation?

To which what must you answer (reader so divinely frank!) but Oh, I believe in retaliation. I know it on my skin.

Me too. There is not a soul, is there? who has not tasted someone’s idea of just deserts. Isn’t it pleasant when acquaintances agree, as we do, about some topic, such as retaliation? This is what they mean, I guess, by the “ideal” reader. It is important to have faith! And we believe, we two, in the reality of retaliation. We have watched the erection of this stairway to heaven. Its other name is “escalation.” I wouldn’t scale it, it does not bear much. The aim is, serve ’em right. I mean, they asked for it since we noticed them.

And you know, delightful reader, when we say someone is in trouble, we say they are between a rock and a hard place. If that is trouble, I say, being something of a geognost, bring it on. Lapidation is one way to heal a community and, like a Maytime fair, promote important interests. No one wants to cast the last stone, it’s no fun. “More weight” was what, under the circumstances, one elderly gent requested, I will not abuse his memory here. Whereas Goethe asked for light, a lighter matter. Stones may change to other things in mid-flight, of course. A kiss, a garland, a bird.

Reader, you are a wit when you imagine that some thus approved might say, Thank you for the mineral collection. A pleasant woman when I was a child gave me a small one, hers was the first place I ever had a chickadee land on my hand. The fact is, I love rock outcroppings and I am very happy when, passing a vegetable patch here in Van Dusen Gardens, and a famous dogwood tree and a bank of less famous roses (one named for Emily Carr), we come across rocks in the midst of other things scarcely distinguishable from those I have revered in Nova Scotia, in Ontario, in the Rockies of Alberta and (of course) here in British Columbia. You would think the naked rock bleak. It is not. It has something of the quality of a golden retriever leaning against you with fidelity that seems to be to you: but it is a fidelity to something both in you and beyond you, an apprehension of fidelity as a force of the universe but not as understood by us nor even by the dog but, possibly, all the same, by the rock. One rock outcropping comes to mind today, in trembling aspens and sugar maples Red-eyed Vireos sang the day away, I loved them so much I hated them for having to die and for having to change, to change because Darwin seems to be right, and hated the world for dying because it must or so the astronomers say. I didn’t want immortality for myself but for them. They kept asking a question and supplying an answer but there was no question and there was no answer.

Later, when I studied in a foreign country and there were difficulties, it seemed the rock broke through me and predicted, rightly, a happy outcome in the following verses I now take pains to inscribe anew, their virtù I think intact a quarter century later, while a Ruby-crowned Kinglet bubbles, unrepressed—a winged source justifying the ways of providence to us from the pear tree no less a vindicator of the same:

Little Spider Bay Landscape

Ever wonder why they call that rock

Metamorphic? Yes you’re right

My grandmother is the process.

No you could not pull my grandmother away from

Sunsets they pressed down on her and there was

No getting her out from

Under. Millstones, hear them?

Grinding the odour of pine.

It would be like

Stripping up the outcrop between here

And Gooseneck Bay.

On the rock by the water she sat down.

Sentiment died like a fire.

Each nest was fitted into whorls of the spreading juniper

Immovably as a sun in its fire. A knot in wood.

The water of the bay

Was filling up like a blood

Bath with evacuated day.

She was spreading on the rock like moss.

Each sunset would sit down on the moss

As if to watch the sunset on softness of the moss

And reverberation of the sunset was slow as moss

And soft as moss and took as long to grow its end

As moss and shadow sat on the moss and the moss

Went to sleep on the rock in the bleeding veins

Of the pine smell blood in the night lapping the rock.

The rock excuse me

Which was the Throne of Night now

Whose sceptre is a bleeding pine

Whose crest is the woodpecker’s crest is the cry

Of the woodpecker whose sliver enters

The palm of the bay where

Loon like a pine torch dives after

The afterliving of the sun wreck.

Who can get those stars out of the cracks in the water?

The stars are like teeth in the smiles of the water.

Meet my grandmother Nox Perpetua.

You’ll find her where the sun fell.

She is busy changing sentiment changing it

That’s why her rock is called metamorphic.

The wrinkles in her palm are moving the ripples in the bay.

Sentimental maybe, why even a line blushes to admit as much. But, reader, when a voice like that one chooses to whisper in your young ear you know you are lucky and, faithful or faithless, you cannot help but give thanks. Everything went fine in the end, all is forgiven whatever that means, it isn’t a matter of meaning. I am the only one on earth with the right to make this judgement. Joe Blades, endeared to memory, later published this poem for me in Fredericton, New Brunswick, in 1999.

Vivito

So, here in the sleepy asylum of August, when, for the moment, we are “insiders” (I suppose) of Van Dusen Gardens not “outsiders” (I suppose), you choose to ask me, reader, out of the blue, Do you believe in cause and effect?

And I have to ask (repressing the plosive expansion of a yawn), Do you really want to bring that up again?

—No, you say and strangely, sad reader, you confess in this way a heart’s truth! Confession is something many approve of. All right then! Brandish your bleeding heart! Reader, you may trust me, I will listen.

—People have been trying to cram me into a paltry story you say.

I have to object. Are you insinuating, presumptuous reader, that this present story is a paltry story?

—Oh no, you say, not the present story. I mean they are trying to tell me the story of my life. For example, one of the principles of my life is, everything I do is because I was once a child! I should admit before the jury of my peers that my parents beat me!

Reader, did papa and mama batter you, bruise you?

—No. I was slapped once that I remember.

If it never happened, then—such a sad case!—abuse was not consummated on you, not by your loving father or by your loving mother, no aunts or uncles smashed your face or twitched your private parts. Nor did your sisters nor your brothers. Cousins, including those twice removed, behaved civil, tragically, and standoffish in the matter of force, renouncing (such tact!) even a verbal order of violence. Non-consummation is sometimes devoutly to be wished!

—In a word, I don’t believe the story of my life that I am told.

—Funny the standard biographies are issued these days. But you do believe in retaliation?

—Yes, yes: let us arise and go now, and go pile up a temple, Vengeance is an ancient god. I would site our fane over there, by the copse. Let’s make it formal. Then let’s collapse it on the worshippers! Poor fortunates, they have never had the chance to find out whether they are cowards, or not.

Good, reader, we’re not nihilists. We believe in principle! Retaliation, like the voice of poetry, exists. See how we diversify as we go! And, importantly, we are political animals, isn’t that the rusty old binomial? It rasps and creaks, it flakes when I pick it up, the rain in Vancouver is simply legendary. Aristotle made that up, I think, “political animal.” Do you trust him? I mean you know he was a Greek. Indulge me, let’s talk philosophy. If retaliation is a principle, is it a principle of the universe or of society?

—Society.

So we agree. Not the universe!—preposterous!—though Linnaeus rather incredibly alleged as much. He had a motto in that line, Innocue vivito numen adest: In time to come live innocently, for a spirit is here. The emphasis, as you see, is on that most traumatic of tenses: the future. He was a little wacky I’d say, believing in what he called Divine Nemesis. But let’s be reasonable, let’s restrict our inquiry to society. To reaffirm our opinion, then, answer me: is retaliation a principle of society?

—For sure.

For sure. Vigilantes are tiresome, by definition they never get any sleep, they see too much and therefore see too little, they discount vision therefore in the proper sense of that word. Retaliation is in any case a mere idea, Vengeance is mine saith the Lord and there are no Lords around here that I can see, we may babble whatever nonsense we wish, it used to be called “freedom,” now we will move on. Move along then, come this way where look! what wonders: the Dawn Redwoods. Dawn is a time of day, these trees steeply perpetuate it. There’s the real happy hour. How sweet the sepia shadow this stubby-limbed tapering Panurge affords us. Munificent beyond our deserts, sinners that we are: the antithesis of Retaliation, a garden proposes sua sponte other topics of conversation. For example: is a garden natural or unnatural?

Natural

“Natural” used to mean a fool. What is foolishness? Being tame, sometimes. The Galapagos in this sense is an archipelago of fools. Look what’s happening to them. Tame and wild, not an antithesis. We expatiate in Van Dusen Gardens, however, and isn’t this a habitat well suited for some speculation about the unnatural too? It makes me think of the phrase “stool pigeon.” You look puzzled, let me explain that it is criminal argot for a delator. Unfair when you know the facts. The days when Passenger Pigeons still darkened the sun, it was the bird, a living breathing decoy, the hunters used to fool those naturals, other Passenger Pigeons, into landing where the net, the trap and the gun awaited. I promised I would talk about Passenger Pigeons, let us return to 1792, Elizabeth Simcoe has arrived at a settlement along the Saint Lawrence, the bugs are bad. Beware, it’s a little sentimental. I sketched these scenes twelve, thirteen years ago. The transcription remains accurate.

The rights and liberties of the subject

The low houses of Cap de la Magdelaine stare at the visitors and at one another over fences cunningly high enough to conceal on one side a person staring in, and on the other a person staring out. Fair is fair, after all. How fiercely mutual incrimination rises! Inspection hangs over the town. Miasma of the inbred gaze, a pollution issuing when incompatible standards of rectitude combine, forms like a vapour. Does it lock tight? It does not cohere. Crooked timbers leave their gaps.

Elizabeth dizzy, she hoods her head to baffle the siphons of the bugs. The venom they have jetted into her system stuns more than the blood they have taken. She cannot collect into her harassed chest such molestful inhalations. Strugglers gum her tongue. They toil in the glue of her nostrils, wedge in her slippery ears. Evidently they judge themselves righteous. On what basis do I draw this conclusion? They keep on drawing my blood. I will not collectivize myself, for their sake. How to be so very, so very… right?

Then (before the burning porch of her ear, not before her thin gaze) appears a phantasm. He is perplexing. He says chagrined, I am the chief magistrate and constable of mosquitoes. Forgive us our trespasses, he says. Does he say? Elizabeth thinks, But his extractive mouth-parts are not dedicated to reasonable speech. He keens with his wings, this insect. That’s it. My doom is to hear. Forgive us our trespasses (whines the constable), as we do not forgive yours. Let yours be ours.

—Let yours be ours the chief magistrate and constable pursues her with his serenade, not exactly a Ruth entreating a Naomi. And he pursues his theme, of confiscation. Let yours be ours. Learn the absolute degree of our loyalty to your possessions and to you. “Thine” obfuscates with a defective name what is ours to take. The Constitution writ in your taken blood proclaims “You will lose less, if you consent to be lessened.” Give—that is, give up. Here the rights and liberties of the subject are subject to revision. We will block any trajectorium your circulatory intimacy intends. We will intercept your cardiac dispatches, and culling such ichor as they would condense, stick our innumerable refusal of your ownership back where it belongs: in you. Be plethoric, be moribund: prime us always as we run out. We are the rightful heirs of your blood, more than the children descended of your love and blood. See we seize their estate at which you still labour before you have so much as died from the earth. It is ours so long as you shall live. The droit d’aubaine is but the shadow of our law. And he falls still a pulse or two rapt by that purloined secret.

So the bugs swill the wine of the heart: not their own heart. Who said that, and was it said with wings or lips? Elizabeth looks round and sees no one and nothing. Meanwhile, Cap de la Magdelaine’s stale incest of witness breaks off. Look at the prospect of fresh provender these visiting dignitaries promise. We can at least relieve them of their dignity if of nothing more substantial. Look! There is the Governor of the Province upstream, his Lady and their itchy, cramped entourage. They unkink. Ashore they stalk around, and they lengthen their strings. The mosquitoes have not dispersed. Now the mid-river mob mingles with the townies, gossiping with blood-savouring breath, before into the veins the parched tubes plunge once more. Each—its flight a complaint—comes on, equipped frontally with a pair of probes. One robs. The other drugs. Their views they meanwhile insinuate with pipes of petty wings. They suck the great and little hearts. They must lay their eggs mustn’t they, enriched by giants—as the spigoted maple also concedes its syrup? Tall are men and women and Elizabeth can ennoble all humanity, when she sets it against the vexatious insect. Here she rests, burning in her bites.

William Harvey throbs into her thoughts. What a heart that man had! Her heart stirs. He called his heart and her heart and every heart “the sun of a microcosm.” This immortal cardiognost loved also to look at birds. Think of hearts—and of birds. Contract! Expand! Describe the circle that seems to confine you. To describe any circle is, impossibly and really, to exceed it—and to pass out from inside the circumference without rupturing that space. To our good drummer make our rounds, in spite of the looting. Blood-flow is liquid thought. Did I understand that, before? The drummer wears brighter and more fanciful clothes than the rest of the regiment. He is not echo: he is origin. The chief magistrate and constable swells again into audibility wailing, Forget your rights and your liberties. Never forget I beset your paradises with my featherless eaglets, and—mimicking your inmost rhythm—prey on your measure and your impulse. She slaps him flat.

Fly

—No you must make it look natural.

Miss Sone and Pierre Nordir and Monsieur Stéphane round a clapboard corner of Cap de la Magdelaine, the town so small it is all outskirts yet dense set.

—Natural. I said “natural.” Don’t you know, what “natural” means?

“Natural” repeating would strike home, as an axe strikes. “Natural” like an axe-blade would glare as it strikes. The adjective would hack at the acoustical realm, to provoke a most terrific tympanic reverberation. In default it extorts only a demi-echo, deadened by environs perhaps too self-enchanted to yield back quite the desired image—or to cleave to it. The sharp voice does not forego (for all its edge) a rude unctuousness. It smacks of the dramaturge, and what kind of theatre might we overhear? This brute fop of sound with which our three listeners are now acquainted pleases itself with displeasure, preens over its very aggravation and successfully infuses with its invasive tremolo the space that still baulks it the full bass reflex of its powers. It decoys its audience with the insolent phantom of forgiveness, at the end of the impasse where the promise is broken. Who—or what—has ever got absolution of such conceit? Vanity does hamper efficiency…

A bird wings up over rooftops: is yanked hard back by bonds. Now see! those legs are longer than we would have supposed. Other circumstances would never put us in a position to suppose.

—Not like that. The others will never believe it. They won’t believe—they won’t follow—if you do it like that. You must do it more—raffiné: thus. It must appear the bird had decided all this, for himself. Every move: and its sense.

Is it a mage, a philosopher who speaks? “Free will” says the voice. “Learn to manage the show of volition. Well you yourself—you cannot choose. You must learn to perform it: free will.”

The bird whirls straining at the limits of his strings. Feet drawn down, legs stretched out by the aspirant clap of his wings, he reaches his poor apex. Now hands of human make compel his descent in circles gentle of subsiding aspect as a bird could of choice. Here their tackle, however, kites his life. Up the bird flaps again. Apprentice-like ineptitude taking a crass turn at manipulation tears the fowl thrashing from his angle of ascent. The fracas awkwardness (a wrestling midair between the dove and the terrestrial puppeteer) dislodges a feather from his breast. The plumage of the dove kind sits lightly implanted in its follicles. This feather freed into a career of its own (lighter by far than the thrown bird) flies—as in quest of relief—over the rooftop, to sail above Monsieur Stéphane, Monsieur Pierre, and Miss Sone still come to a stand round their blind corner.

A wingèd slap, invisible, rounds that corner, imparted guessably from speaker to listener. The slap wins what the loud voice could not. It can slap up further slaps from crisp repercussion. In such hard-returned hardness it formalizes the only resonance to be evoked from the place: the echoing impact of killing, killing (for example) mosquitoes—and needing, then, to kill them all over again.

—A flyer must look real. Only look at what they take for real. And now the voice pushes more softly, seeking by flutter and caress to improve its deeper entry.

(This plume must derive from a turtledove Thomas thinks: must come from a passenger pigeon. For the same leurre-bird’s ruddyish-fawn breast-feather from a couple of streets down, settles on the proscenium of his palm.)

Beside Monsieur Stéphane, Monsieur Pierre sees a bird crest the roofs now. The dove flaps more willfully, far, than the forfeited breast-feather’s swirling flight until Pierre’s gaze, hardening, perceives the art or deceit of it and his shoulders bunch. Had his shoulders the roots of wings he would spring up. Other pigeons beat nearer. Each would seem in fact rather than approaching Cap de la Magdelaine, to enlarge individually from a still point above the earth. For the longest time they swell in their place, add detail to their forms, all without looking to come any closer. The exhibition that we witness meanwhile augments the impression that they make, in spite of its fairground staginess. The decoy here is less a particular bird than it is the instinct of trust.

At first, we can reckon the credulous comers on our fingers. But we must soon discard our body and its few digits as any kind of computational tool. Even the more masterful eye, losing mastery, can no longer subdue the flock to the precision of census. Although they are succumbing to a human ruse, the pigeons still escape the calculus of the human body where our original intuition of arithmetic must have set up her temple. We give up efforts to tally the birds as they throng toward us. We are swept by ignorance now. Not “passenger,” but “numberless” pigeons. We must receive them weather-like dumbly. Miss Sone and Pierre and Monsieur Stéphane finally round the corner in the opposite direction from the one that the slap had lately taken. In a bucket, a deerfly (ruby its lidless eye) winks up at Cassie not with that eye, but with its whole rocking corpse pillowed on dimpled liquid. It swims better dead than alive. Alongside it, in the round mirror of the water, flash swarming blurts of turtledoves reflected from above Miss Sone. Arrows from longbows occurs to her. Look now! Stands a blond man grinning. Beside him a younger man, just as blond, does not grin. The latter (the disciple) holds the turtledove tight, the strings trailing on the ground. Across a tamped-down turf—hard mud, matted grass—some temptation for turtledoves has to have been sown. In the midst of this, a modest troupe has already alighted. These pioneers, in the generosity of their sparsity, divide the spoils without sparring or controversy among themselves.

What about the eyes? Pierre stares at the turtledove in his jesses leashed, he seems… blind. A thread knotted over the head ends in an eyelid, Pierre guesses from the disposition of the thread that both eyelids have been drawn tight, thus, over the crown of the bird, to shut up his vision. I will knock out your eyes, I have heard that threat myself.

—What are you doing to the turtledove? he asks, his striding toward the apprentice not harshening his delivery. The apprentice by way of response looks to his companion, the high and beamy man who having issued instructions only rejoins Doing to him? My friend here Michèle Youvique is simply holding that turtledove, while the others—the others enjoy the salt we have strewn for them.

—But you have blinded him and you are jerking him in the air, so, and you are I think more than hurting him says Pierre hands at his sides, like weapons that might be hung in an Ithacan storeroom.

—Blinded him? says the man sly. He makes if to turn his back on Pierre then spins round and punches him in an eye. Blinded, you can say you were blinded by D’Arcy-Empé de Sebcy: and you will not forget it. Forever, he ventures to destine the bateauman. He has a key protruding from his fist and he has driven the house-key into Pierre’s eye: but it has only gone into a canthus, which beads and runs red gashed by black, serrated metal. Sebcy bends down and grabs the cords that attach to the turtledove’s feet, tears the fanning bird from Michèle’s grasp.

—You want to see him not flying like this any longer then? he asks of Pierre who has bent double at an unseen, unfended-off blow from helpful Michèle.

Sebcy snaps the bird’s wings, and tosses him to earth. Now fly damn you!

Pierre crouching shuffles as groveling to Sebcy closer, pulls himself up as he can and lands a blow on Sebcy’s cheek, avoiding the jaw. Natty Collins impinges on Pierre’s sense running from some direction, with Thomas. Two strange women shriek something.

Pierre gathers up the grunting blind scuffler, the peltering wing-tip trailer, yells waving at the others Fly, all swerve off. Youvique has run away but Sebcy stunned stands tethered to aftershock, both hands on his cheek: not concealing the edges of a new bruise there. Presently great Sebcy falls back on the ground, quite as if he had chosen to do so.

You cannot call it prison

Pierre Nordir wakens in a fluttering dark, in a clinging reek. Beer sticks on him. I do not like beer. Yet his weakness at first interprets this gummy residue as the significant agent in the detention he now apprehends. The other stink, however—which disgusts him—matches no process or product of fermentation he can recognize. Not in the beer, it permeates his sense of smell. The inhuman taste in his human mouth not his blood, his tongue cakes dryly on his aridity. In the pharmaceutical waste of what congeals bitter, pill-like, into him, himself, only the tongue stirs, curling to wet itself according to its custom: and it cannot. A drug has come like a pack of strangers seeking to stamp out his every proper thought. But he—blurred, with cankers lighting up his inward mouth—has found a thought. Defiant-careful he picks it up in its blur, as of feathers.

From positions seemingly beyond him, sores radiate claims on him and overlap in disputatious multiplicity. They ache differently from habitual pain, the strain of rowing. Nudging a headache across the terrain of an emergent bodiliness, he adjusts his former, easeful picture of his joints and his organs to these disarticulations and halt processes. Now wait. Wait. Have strangers implanted blows all over him? Have they as a plumage stuck them point-end first into his skin? A suit of contusions spangles him. It glows without supplying a lamp’s illumination. It patterns pulsing spots across his sheath. Bruises: he can scout their rims. But he cannot see them. Punctilious tailors have fitted him with a uniform that throbs straitly with his heartbeat, half beneath his surface and half (he could believe) above and beyond him. Many attempts at his death have variegated him. They have been thorough but superficial assassins. Still he wears the livery of their violent failure. The live thread of his nerves stitches the costume. The drug is meant cooperatively to soak an indelible pattern into the fabric. They would prefer him a chemical—not a man. Mortar and pestle are important for preparing the dose.

Light comes dull, dully goes. Sometimes he hears an éclat de rire resembling his own (I have a margin here, even for a desolate exercise of vanity he thinks). But this mirth does not shake his diaphragm. Cruelty binds him to it. He extrapolates as best he can from his nerves. Perhaps I am the object of cruelty. Cruelty exists between the knuckles and the object. Once it has crossed that divide, it tarries in the space with him. He has to live with it, or die of it. They may agree (whoever they are) they have suspended it. Still it goes on. He stares at it with all the pores of his skin. Pierre thinks These words come to me an excess, a surplus: therefore the pain will not kill me. I know more than the ones who did this to me. He thanks the words that they come. The cruel do not know (he thinks) how cruel they are. A matter of knowledge on his part: not of pity. They leave their cruelty behind, and go. Then you cannot call them cruel as they in fact are. For they have not recognized what their cruelty is. Have they done what they have done, if they do not recognize it? And the question of fault (their fault)—guilt, their guilt—rises before his rising curiosity, and through the ringing of his bruises and binding of his limbs. The consequences of cruelty, how great!—though the cruel remain blind to it, blind as (that was the bird) a blinded dove, or blind as Pierre in his dark room not wholly dark. You cannot call it prison: there was no trial.

Treasures

Pierre wants to explain that the bruises have lain on him hard but now their weight is dissipating as sometimes, confronting a task, you think “I can never do this.” The rhythm, however, comes in, and the task is well underway. He has been lifting the bruises from him, bruise by bruise. He puts them deep (deeper even than the bruisers had wished). He keeps every one carefully there. Presently they are not bruises: what they are he cannot explain: but they have a use, or will have one. They will, is his faith. The inverse of a bruise is treasure and Sebcy has given Pierre treasures, many. Pierre glints with his emolument.

The frontispiece of Blake’s “Book of Thel” is from blakearchive.org.

“Little Spider Bay Landscape” appears in Song of the Vulgar Starling.