by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Like clockwork, every year around the spring equinox, the ducks and egrets would return to the river in Tochigi. And sprigs of green grass would start sprouting in our lawn. This was when people started taking to the hills to pick mountain vegetables, herbs, and other wild foods. My son loved looking for ferns and fiddleheads. In Japan, this meant warabi (bracken fern), zenmai (osmund or cinnamon fern) and kogomi (ostrich fern). We enjoyed going “baby fern hunting.” The delicacies could be found along a trail a bike-ride away from our house. Like little coiled springs, the fiddleheads seemed waiting for just the right moment to unfurl.

Old like dragonflies, ferns once covered prehistoric forests. My son and I loved imagining ourselves wandering in a never-ending fern forest as gigantic dinosaurs soared in the skies above our heads. The mist-covered hill near our house, just waking up from winter was the home of fiddleheads, lilies and dogtooth violets. And there was an ancient shrine standing guard at the summit.

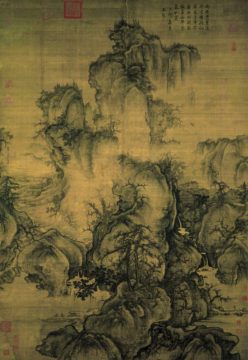

“Mountains smiling in early spring” –Borrowed like so many things from China, the poetic trope was made famous in Japan by the Northern Song painter Guo Xi, whose poem about mountains smiling and laughing in spring appeared in an poetry anthology in Japanese known as 漢詩集 「臥遊録」 Chinese Poetry Anthology Dream Journey Jottings:

春山淡治而如笑

夏山蒼翠而如滴

秋山明浄而如粧

冬山惨淡而如眠

“Mountains smiling in early spring” was an image much appreciated in Japanese haiku. After what must have felt like an unendingly long period of cold and depressing “mountains sleeping,” the mountains in March would seem to almost “spring” to life again.

笑= can mean smiling and/or laughing: oh, how this has tormented translators of Japanese and Chinese…

2.

2.

I once read that the custom of cherry blossom-viewing—sometimes referred to as the “cult of the cherry blossom”– had its roots in the Chinese Qingming Festival, a day when people in China travel back to their hometowns to sweep the tombs of their ancestors and celebrate the return of spring. It was customary on this day to take to the hills 踏青—getting out in nature, to hike and picnic with family and friends. People also probably engaged in picking mountain herbs 山菜摘み.

It was this idea, of “stepping on blue-green” (踏青→ getting out and walking in nature), along with the Japanese idea of the gods of the fields returning from their long slumber around this time of year that are most deeply connected to Japanese sensibilities surrounding cherry blossom viewing.

Something interesting I realized in Japan was that while a person goes “cherry blossom viewing” 花見, in fall they go “maple leaf hunting” 紅葉狩り. Like picking mountain herbs or foraging for mushrooms, beautiful maple leaves were gathered and brought home. For tempura? For attaching to letters to loved ones? Or for pressing in books ot albums?

This is what I am thinking about this spring: this deep impulse to get out in nature and not just look with my eyes—but to listen deeply to insects singing and flowers blossoming, to smell and taste… and to touch.

Perfectly timed to appear along with the spring equinox this year is Winifred Bird’s Eating Wild Japan: Tracking the Culture of Foraged Foods, with a Guide to Plants and Recipes.

Looking forward to reading it for months, I realized that I have never—not even one time—eaten something I have foraged myself. Not only have I never gone into the woods to gather mushrooms, but I have never dug for clams or picked wild berries. There is a row of gingko trees a ten-minute-walk away that produce opulent gingko nuts. I pass them on my daily walk and look forward to watching the drama unfold in smell!

A friend urged me: Grab them! Such a delicacy—but I am too afraid of pesticides, too untrusting of my city. And so I buy mine in cans.

I do love to gather leaves and flowers and press them in books, but hesitate –no I am terrified—of putting anything gathered into my mouth. Afraid is my middle name. So, I forage for flowers and leaves.

In her book, Bird ponders that there is no perfect mapping onto Japanese of the English concept of “foraged foods.” In English, wild or foraged foods can include anything that is not a product of agriculture—from wild boar and wild mushrooms to dandelions picked in empty lots and seaweed collected on rocks along the seashore. Perhaps because foraged foods have always been part of the Japanese way of “getting out in nature,” there is not an all-encompassing term. The closest word, muses Bird, is sansai 山菜, which denotes mountain vegetables and herbs and can sometimes include nuts and mushrooms.

3.

3.

Receiving gifts of food in Japan was a never-ending delight. It never failed, a week or two would go by and my doorbell would ring with one of my friends or neighbors bringing food to share. And sometimes it was foraged or wild-crafted. It seemed like everyone had a forager in their family who would send large care-packages to be shared.

Wild seaweeds, fish and the much loved turban shellfish known as sazae—and, of course mushrooms, like matsutake.

In her book Mushroom at the End of the World, California anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing begins her long meditation on late-capitalist commodity chains and devastated landscapes by looking at the way Enlightenment philosophy was itself built on this concept of mind-body duality to view nature (as lacking in mind and soul) as being set apart from human beings. While it may be grand and universal, it is also passive and mechanical, she says. Nature is seen as more of a backdrop and resource. Something to be used; for which “the moral intentionality of man, which could tame and master.” Her book is interesting as it avoids the use of the word “anthropocene,” instead describing our current state of being as one of “post-capitalist ruin.”

This is crucial, for according to Tsing, the history of the human accumulation of wealth has turned not only the environment but also human beings ourselves into resources and this has led to the state of deep alienation we find ourselves in. From economic theories of self-interest to scientific theories of the selfish gene, we have come to view ourselves as being isolated. Encapsulated in bodies, alienated from nature and from our fellow critters. And it is in this lack of understanding of interconnectedness that is leading to our ruin.

When friends brought these gifts from the sea or forest, I always trusted them to be safe—since I believed my friends were not as alienated from nature as I was.

In Bird’s book, she makes a wonderful point that some environmentalists make as well, that people who use the land in cultivation or in foraging are more apt to protect the land, since their livelihood depends on it. Locally-based, human intervention that takes into account the terroir of certain place will by necessity be more in tune to the eco-system. Terroir wines, slow food and foraging resist the corporatization of food and global commodity chains that have done so much harm to the land.

Fly-fishing last year in Idaho, we listened to our guide talking about how he shopped for food two or three times a year. They were, he said, self-sufficient on the land. It was his life and his livelihood, so the health of the ecosystem was his top-priority. Fly-fishing is a sport that is designed to pretty much be as difficult as possible to catch a fish. But like birders, fishing fly, says Mark Kurlansky in his book Fly-Fishing, embed themselves in nature, experiencing life “first hand.” By touching or seeing, hearing, smelling and tasting.

4.

4.

In George Monbiot’s 2013 book Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, he talks about rewilding as on-going practice. Instead of a predetermined endpoint or ideal ecosystem that is then conserved, he calls for a different relationship between people and the land. One that will be healthier for the people, who are, he says, ecologically bored: “As our lives have become tamer and more predictable, as the abundance and diversity of nature have declined, as our physical challenges have diminished to the point at which the greatest trial of strength and ingenuity we face is opening a badly designed packet of nuts, could these imaginary creatures have brought us something we miss?”

And he makes very much the same point that Bird makes that a healthy-use of land by local people will entail a real stewardship since the people’s livelihood depends on keeping it healthy.

While, Monbiot focuses on a new relationship between human beings and nature, Kim Stanley Robinson called for a serious commitment to rewilding in his novel, Ministry of the Future, which I wrote about here in these pages last year.

KSR says:

To Fight Climate Change, We Will Need Every Arrow in Our Quiver. And that is precisely right, I think. We need to hit the problem from various angles and try to push down the amount of carbon emitted using all we’ve got –from city planning and economics to multiple kinds of technologies and geo-engineering “fixes.”. And so in the novel, we follow along with experiments in a blockchain-regulated “carbon coin,” that would be paid to states, corporations, and individuals who succeed in sequestering carbon instead of spewing it into the atmosphere; massive re-wilding (half earth), and the replacement of gasoline-fueled airplanes with airships (we saw these large helium balloons in one of his previous novels as well); similarly, there are tanker ships fueled by wind and solar; and the replacement of predatory social media with publicly owned platforms.

Solarpunk at its best!

His imagined future would see large swaths of the world returned to nature.

5.

I think we should also consider (Maybe KSR did) transitional zones, akin to the traditional Japanese concept of satoyama.

Made famous by none-other than Totoro, satoyama—a mix of small-scale farmland, rice fields, and wetlands, as well as its surrounding woods is not pristine or untouched. Its objective has always been human use—but they are sustainably so. They are, in effect, the polar opposite of the massive-scale monocrop agriculture tracks owned by corporations in the U.S. mid-West.

In 2010, when the UN held its Convention on Biological Diversity Biodiversity in Nagoya, Kyoto Journal (a magazine I am proud to have worked with for twenty years!) devoted a special issue to biodiversity and satoyama. Some have compared the Kyoto of our time to Paris in the 20s, with its vibrant expat art and literary scene. This is how I first learned of Winifred Bird’s writing and I have been a fan ever since. Some people might know about satoyama from the fabulous BBC documentary with David Attenborough from years ago, called Satoyama: Japan’s Secret Water Gardens.

A kind of commons, they are communally used and communally managed transition zones between forests and rice fields and villages. Streams, ponds and rivers are used as water sources for paddies, and people make limited use of the forested areas to forage and hunt.

6.

6.

Monbiot’s book is interesting because it has a focus in how alienating it is for human beings to be cut off from the natural world.

This is something I think about a lot since returning to the US from Japan—almost ten years ago. How is it possible that surrounded by nature as I am in beautiful California that I feel this alienated?

I guess the other way of asking this is how can I not feel cut off from the natural world without all the seasonal festivities that so totally defined my life in the Japanese countryside? Even in Tokyo, we lived very close to a rice paddy and along with the other seasonal festivals, the rhythms of the paddies defined the the landscape and the soundscape.

We talked and wrote about the weather and seasons, how the foods we ate changed season by season, celebrating the flowering trees and the sound of the wind arriving in fall. It was this noticing of the world, this embeddedness, that is missing in my life in California.

No matter how many times I update my seasonal blog or write posts like this, this shared wonder is no longer a part of my daily life.

In the early days of the pandemic, I dreamt I was in Alaska walking on soft, spongy tundra. Colorful wildflowers were sprouting up here and there. I wanted to take off my shoes and walk barefoot so I could feel the earth between my toes. Slipping out of my sneakers, blue butterflies flew out of my shoes. It was an incredibly vivid dream of childhood wonder, which was maybe the last time I walked outdoors barefoot!

Bird quotes a seaweed forager in Japan who worries that our relationship with nature is fading, when the ocean is reduced to scenic location, something that flows in and out with the tide. This is why she believes in a conservation ethic is best fostered when local people make moderate use of the ocean’s resources and thus gain more personal motivation to care for it. The ocean becomes a part of their kitchens, their meals, and hence their very bodies.

And who knew that the Victorians in England were crazy about collecting seaweed? It was especially popular among young women – as a way to connect with nature. Replacing restrictive bodices with more comfortable and practical attire, they could let both body and mind run free in the wild and enchanting world.

7.

7.

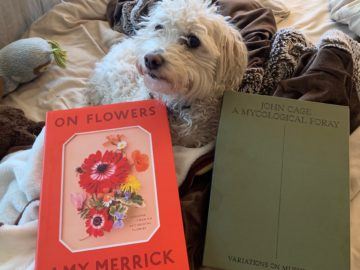

Did you know John Cage was obsessed by mushrooms? Unlike me, he was not nervous about foraging, but still he found himself in a bit of trouble after eating one that unexpectedly caused his blood pressure to drop dramatically. He became violently ill and had to be rushed to the hospital.

Talk about a walk on the wild side: fantastic fungi– magical, mysterious and mischievous. Dastardly and deadly.

Gina Rae La Cerva, in her book Feasting Wild, talks about the way foraged wild foods, once associated with poverty, have become rare luxury goods.

She starts her book off by visiting Copenhagen to eat at Noma, one of the great restaurants in the world. I am not a foodie (yes, you are, says my husband), but Noma is a place I would like to try once. That the food is Scandinavian, local, and often foraged is one reason. But more than that, I am fascinated by pickles and fermentation. And the fermentation chef at the restaurant is a legend. Not unlike my approach to foraging, despite having a shelf of books on fermentation, including the Noma book, I hesitate to try it.

Perhaps because I was raised in an America obsessed by disinfectant I am a bit worried about mold-fermentation. And so I only dream about making nuka pickles like my former husband’s grandma… The first time I visited his hometown, after the family egged me on I put my hand into Grandma’s pickle pot under the sink. I will never forget the squishy warmth and bubbles as I stirred the concoction with my bare hand. This thing was definitely alive! Apparently whatever dirt was on my hand was delectable to the pickle creatures. That is what Jeremy Umansky, Rich Shih, and Sandor Ellix Katz refer to as Koji Alchemy. How I have l wanted to give it a try myself!

There was a scene in Monbiot’s book that I re-read three times. Monbiot is living with the Turkana people in northern Kenya, investigating assaults on them by governmental bodies. He befriends a young man and spends time with him off and on over the course of a few years. There is a moment where he feels envy for his friend, whose life is so interwoven with the people of his village and the surrounding environment. Monbiot says that given the choice at birth to have been born into his life or the life of his nomadic friend, and the choice entailed flourishing in both lives, he would choose that of his friend. He says he is not alone and recounts stories of colonialists in America who were kidnapped in their youth by native peoples. Later ransomed, the men made every effort to return to the native tribes where life was fuller. For all our riches we don’t seem happy.

Is online shopping a repressed urge to forage? asks Monbot. And what of our obsession with “clean” food and celebrity chefs?

In Mark Solms’ groundbreaking new book Hidden Spring, which our own Joan Harvey wrote about last month in these pages, he describes foraging as one of our fundamental human emotions. Joan writes:

SEEKING is a very important emotion, one not discussed as much in more standard categories of affect. All body needs activate this drive. SEEKING generates exploratory behavior, “accompanied by a conscious feeling state that may be characterized as expectancy, interest, curiosity, enthusiasm or optimism.” SEEKING is the foraging behavior of animals; it proactively engages with uncertainty and is the “origin of novelty-seeking and even risk-taking behaviors.” SEEKING is our ‘default’ emotion and the neurons for this arise from the ventral tegmental area of the brainstem, not the cortex.

It really does seem like we are hardwired to get out into the world and see it, hear it, smell it, touch it, taste it.

9.

All the books I mentioned above are part of a revolution in our thinking. One that aims to push back against the corporatization of food and the over-use of land. One that sees our sentience not in the frontal cortex but in a much more ancient part of our brains, something we share with all vertebrates, and perhaps if you have agree with Peter Godfrey Smith’s new book Metazoa, with the entire animal kingdom.

This is the terroir of seaweed and spring greens, of ferns and bamboo, of wild fish and foraged mushrooms. And as Sandor Katz says, “The Revolution will not be microwaved.”

Long live the revolution!

To Read:

The rest of the poem “Mountains Smiling in Spring”

Winifred Bird’s Eating Wild Japan: Tracking the Culture of Foraged Foods, with a Guide to Plants and Recipes

My essay Cauldron Bubble at Dublin Review of Books

My list of Walk on the Wild Side Books

Pickle Notes here.

To Watch:

Documentary Film: Soil! The Movie

Film: Salt of the Earth

BBC Documenatary: Satoyama: Japan’s Secret Water Gardens