by Bill Murray

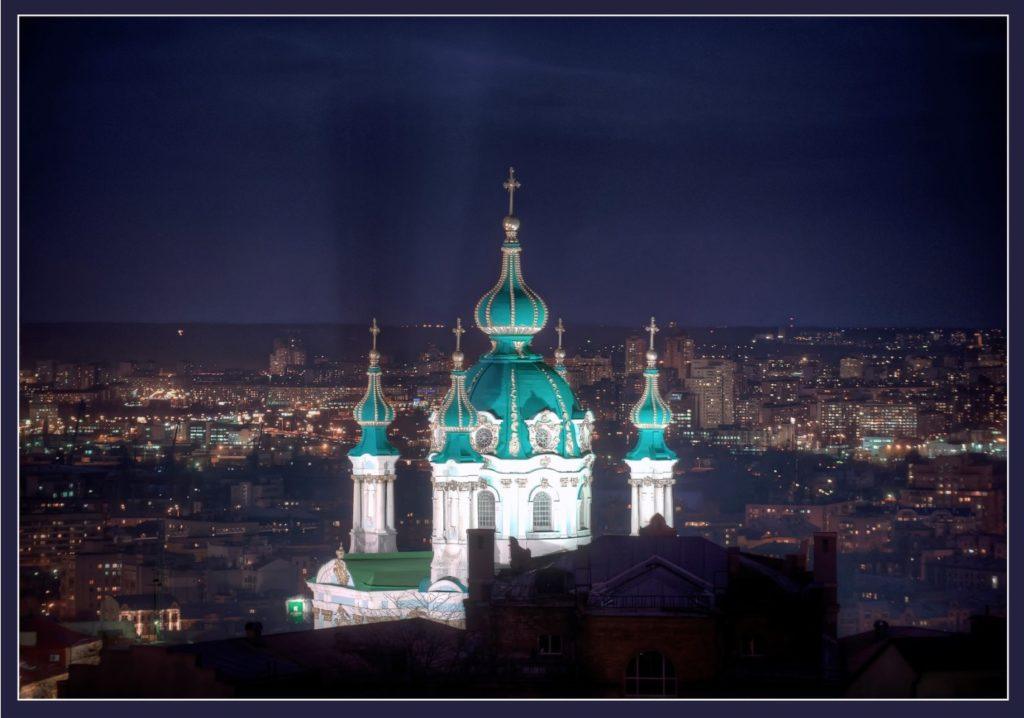

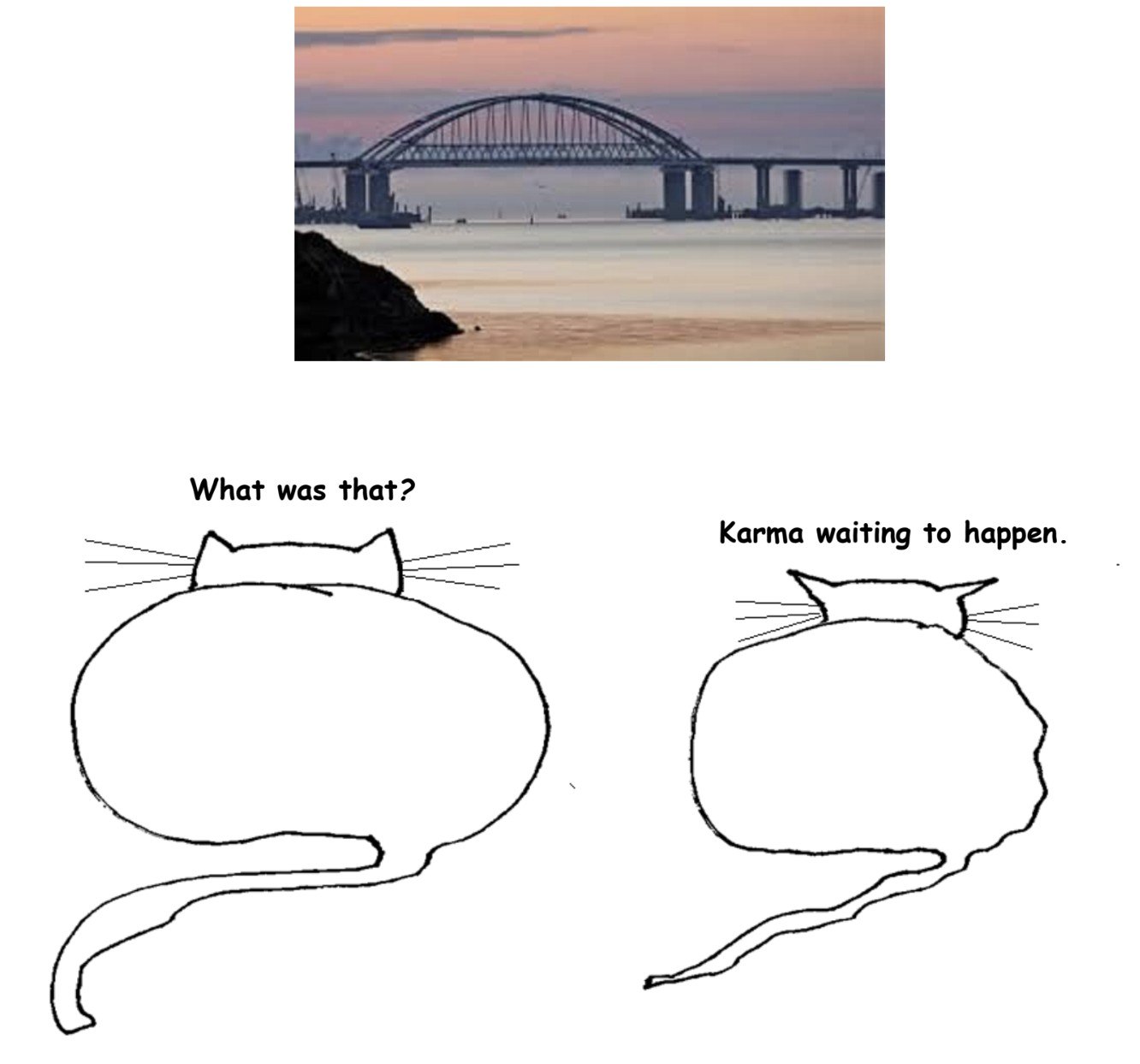

In spring the pandemic lurked. Boris Johnson was Ukraine’s new best friend, Russia’s domination of Ukraine appeared imminent and the UK basked in the queen’s platinum jubilee. I’ve been away since spring. Have I missed anything?

The war continues. Many who caution they can’t get inside Vladimir Putin’s head proclaim from in there that his scheme is to split and outlast a freezing western alliance this winter. We operate from that premise this fall, while minding an added pinch of Kremlin nuclear horseplay.

Putin must now fulminate over his mobilization. Timothy Snyder thinks this war was meant to be played out as a Russian TV event “about a faraway place.” But as the birches fade in Moscow, the fight creeps ever farther into the Motherland.

A month ago I was convinced mobilization wasn’t in the cards, because by the time call-ups got even the most basic training it would be that muddy time of year when the weather constrains fighting vehicles to the roads and the great European plain becomes a great big mess.

So to hell with basic training.

Novaya Gazeta Europe, now operating from Riga, reports that a “hidden article of Russia’s mobilisation order allows the Defence Ministry to draft up to one million reservists into the army,” which may or may not be Putin’s intent. But finer legal points have a distinctly irrelevant feel now, as Commander Putin appears to be personally running the war these days. Read more »

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

Naomi Lawrence. Tierra Frágil, 2022.

Naomi Lawrence. Tierra Frágil, 2022. Come die with me.

Come die with me. by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this:

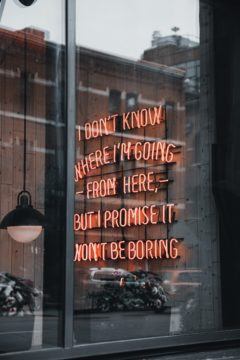

trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this: Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

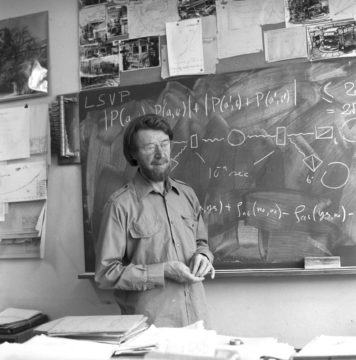

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere.

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere. They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.