by Marie Snyder

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a lack of legislation. A good mandate is put in place when harm can be prevented in an enforceable way. For instance, despite the fact that skin cancer costs many lives each year, and suntan lotion can prevent these deaths, using suntan lotion isn’t mandated. It would be nearly impossible to enforce its use. Seatbelts, on the other hand, have been mandated for decades. In the states, traffic collisions take about six times as many lives as skin cancer*, so seatbelts potentially save more lives than sun lotion. They’re also much more easily noticeable and enforceable.

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a lack of legislation. A good mandate is put in place when harm can be prevented in an enforceable way. For instance, despite the fact that skin cancer costs many lives each year, and suntan lotion can prevent these deaths, using suntan lotion isn’t mandated. It would be nearly impossible to enforce its use. Seatbelts, on the other hand, have been mandated for decades. In the states, traffic collisions take about six times as many lives as skin cancer*, so seatbelts potentially save more lives than sun lotion. They’re also much more easily noticeable and enforceable.

I was just 11 years old, when I was first forced by my mum to strap myself to a car with a 2″ vinyl band with metal clips that held me tight against the seat. It felt like wearing a straight jacket, and I protested the infringement on my freedom. I wasn’t the only one; in many places “resistance was the norm” to seatbelt laws. Mum was avoiding fines of $240 from our Conservative Premier Bill Davis (about $1,200 now), and she was further cajoled by ads on TV showing the aftermath of people thrown from a car. Children weren’t kept from these gruesome images, sometimes shown at school assemblies. Such was the level of care we could expect back in the 1970s.

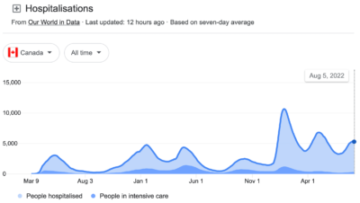

Kids today are being similarly traumatized, it’s suggested, as they’re made to feel suffocated by polypropylene or silicone masks that can cause sweating and sometimes acne. Well, they were, but now they’re free to breathe the unfiltered air in buildings everywhere in many countries despite the elevated chance of someone nearby carrying an infectious disease, which, in some areas, kills more than ten times as many people as car accidents.* Covid hasn’t finished with us. In Canada, recent hospitalization valleys are higher than previous peaks! Read more »

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back. In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.

In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.  Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground? Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading  The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.