by Jonathan Kujawa

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

I once saw a talk by a mathematician near retirement who had made numerous influential discoveries over the years. The recurring theme of the talk was how, time after time, he finally understood everything about his favorite corner of mathematics. The joke, of course, was that each new discovery revealed how his previous “complete” understanding still overlooked interesting and important things.

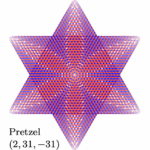

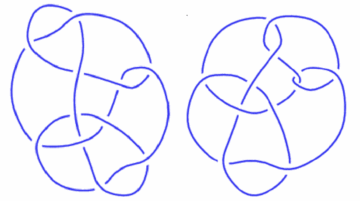

An excellent example of this phenomenon is knot theory. This is the mathematics of figuring out how to distinguish different knots. Two knots could look very different, but could turn out to be the same after some manipulation. Or not! For example, to the right are two knots created by Conway and by Kinoshita-Terasaka. It turns out to be extraordinarily difficult to figure out if they are the same knot or not.

This is one of those kinds of research that politicians and know-nothings love to sneer at. It sounds stupid, trivial, and of no use to anyone. However, if you’re one of those who care about real-world applications, the mathematics of knot theory plays a role in string theory, protein folding, quantum computing, and more.

But if you’re one of those who find math interesting for its own sake, then you’ll be glad to learn that knot theory is a rich vein of mathematics that continually reveals deep, beautiful, and interesting new discoveries. In this essay, I thought I’d share yet another new discovery in knot theory. Longtime readers of 3QD won’t be surprised: we’ve talked about knots many, many, many times over the years. Read more »

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.