by David Kordahl

I’ve been thinking again about the relationship of scientists to the history of science. Lorraine Daston, the historian and philosopher of science, was recently interviewed for Marginalia, where her interviewer asked a strongly worded question. “Scientists are—I don’t want to put it too provocatively—but frankly they’re afraid of the history of their own discipline. What do you think that means?”

Daston was not quite willing to put all the blame at the feet of scientists. Historians of science, she remarked, have become more specialized, making their work less useful to scientists. Likewise, philosophers have failed to “remake of the concept of truth that does justice to the historical dynamism of science.” But then there’s the scientists themselves, who “consider almost anything which is not within their discipline, including other sciences, to be blather. So, there’s quite enough blame to go around in terms of explaining […] this impasse of mutual incomprehension.”

When this interview was released, it prompted some online chatter. Some scientists reading the interview did not see themselves in Daston’s characterization, since scientists do not, in general, consider themselves uninterested in the history of science—quite the opposite. The problem, for such history-interested scientists, was of approach rather than content.

To explore the basic distinction between “science history for scientists” and “science history for historians-and-philosophers-of-science,” I’ll use two complimentary books. Einstein’s Fridge: How the Difference Between Hot and Cold Explains the Universe, out last year from the science writer Paul Sen, exemplifies the former approach, where history provides a narrative scaffold to lead us gently toward our modern scientific theories. Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress, the 2004 work by the historian and philosopher of science Hasok Chang, is a classic example of the latter, where history is used as a proving ground to show that science and its history is more complicated than most scientists care to admit. Read more »

It’s not so much that I’m like my father. Rather, I sometimes feel as I understood him to be.

It’s not so much that I’m like my father. Rather, I sometimes feel as I understood him to be. The anger that escalated at a recent Ottawa-Carlton school board meeting when a trustee proposed and lost a motion to mandate masks, in a setting that typically elicits polite discussion, makes it seem like this type of anger is new and shocking in its inappropriateness. But this

The anger that escalated at a recent Ottawa-Carlton school board meeting when a trustee proposed and lost a motion to mandate masks, in a setting that typically elicits polite discussion, makes it seem like this type of anger is new and shocking in its inappropriateness. But this

The word arrived from the furniture store. They have come! After five months of supply-chain suspended animation, our 15 feet of 72-inch-high bookcases are here. Bibliophiles everywhere (well, everywhere in my family) raised their voices in praise.

The word arrived from the furniture store. They have come! After five months of supply-chain suspended animation, our 15 feet of 72-inch-high bookcases are here. Bibliophiles everywhere (well, everywhere in my family) raised their voices in praise.

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough.

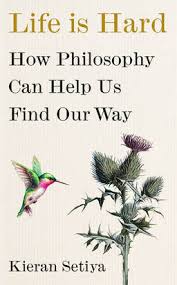

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough. Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import. Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Soon after the pandemic commenced its

Soon after the pandemic commenced its