Just a jet over Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Just a jet over Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

In every generation, young people find causes to champion. Today’s students rally against wars in foreign lands, the environmental record of large companies, the entanglement of Silicon Valley with the Pentagon and China, or the human rights policies of nations like China. These are important causes. In a free country like the United States, protest is not only permitted but celebrated as part of our civic DNA. In fact in a democracy it’s essential: one only has to think of how many petitions and protests were undertaken by women suffragists, by the temperance and the labor movements and by abolitionists to bring about change.

The question is never whether one has the right to protest. The question is how to protest well.

In recent years, I have watched demonstrations take forms that seem more interested in confrontation than persuasion: blocking officials and and other civilians from entering buildings, occupying offices, shouting down speakers, harassing bystanders on their way to work, even destroying property. These actions may satisfy the passions of the moment, but they rarely strengthen the cause. More often they alienate potential allies, harden the opposition, and give critics an excuse to dismiss the substance of the protest altogether. The tragedy is that the cause itself may be just, but the manner of advocacy makes it harder, not easier, for others to listen.

A historical parallel makes the case well. Read more »

by Kyle Munkittrick

Two types of people are very worried about global fertility — social conservatives and Silicon Valley weirdos. I have the rare privilege of having been both at one point in my life, neither at the same time, and, how apropos, I also have training in bioethics. This is my moment.

Pro-natalists want more babies. They argue that total fertility rates being below replacement level is really bad. They’re very probably right. Unfortunately, the conservatives and weirdos not only almost perfectly oppose and cancel out each other, but are also tying their own rhetorical shoelaces together.

The problem of low fertility is a combination of social and technological barriers. Social conservatives tend to want social solutions and oppose technological ones. The Silicon Valley weirdos tend to want the technological solutions and oppose the social options. Combined, both groups end up failing to convince each other and skeptical normies. Who needs anti-natalists when you’ve got pro-natalists like these?

As a result most normal people think the solution fertility problem is obvious. They are wrong. If you think it’s obvious, read Dr. Alice Evan’s interview with Ross Douthat, her blog on Substack, or these threads by @StatisticUrban. If it’s not obvious, what are the probable causes? Read more »

by Lei Wang

If there’s ever an apocalypse, I’ve told my friends, please sacrifice me for your continued survival. Eat me early on, while I still have viable meat. Don’t be shy. I’m not offering out of selflessness; I’d just rather not suffer. I am afraid something might be wrong with the survival part of my brain. After all, just as there is attachment to existence, there is attachment too to non-existence. I am scared of many things, but death itself is not one of them. I fear living more.

I am afraid of injury, of poverty, of failure to meet my own potential—that yawning maw between who I am and who I imagine I could be—most of all of lovelessness, perhaps the root of all fears. Because I guess I still don’t get it. I don’t get how we’re supposed to only love certain people, the ones we know, and not others, though I am as guilty of this as anyone, if not more. How even then, unless you are given permission or related by blood or unless they really need your help in some unequivocal way, you are still supposed to hide your love for the ones you know, lest you overwhelm them. I don’t know why we can love someone and then stop. Or why I’m still trying to make noises of love to people who aren’t making noises of love back. I don’t understand hunger when there is such abundance, when love is free.

To love is to take someone else as part of you, the spiritual teacher Teal Swan says: a form of returning to the wholeness. When you love someone, you are no longer separately acting out of your own self-interests, or your self-interest naturally expands to include those you love. But where is the line between that and codependency, a lack of boundaries?

Mostly, I still don’t get why we can’t just hang out with the people we like, all the time, and preferably somewhere in Italy. Why do we live in different cities? Why is there such a thing as work? Why all these walls? Or space-time at all? These are rather childish questions, I know. Read more »

by Sherman J. Clark

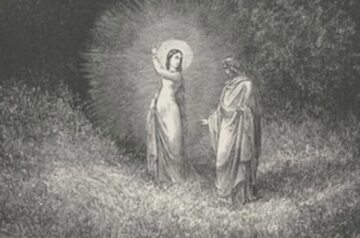

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

We too are often in a kind of dark wood—a thicket of distractions, manipulations, and half-truths. And we are surrounded by guides of a sort—marketers, algorithms, prosperity preachers, podcasters and influencers of every sort, all competing for our attention and trying to shape our desires. But unlike Beatrice, they do not aim to elevate or orient us toward what nourishes. Their purpose is to capture and monetize our attention, to keep us scrolling and buying and craving.

This is not just an annoyance. It is a crisis of desire. Our wants—so deeply bound up with our hopes, our fears, our sense of meaning—are increasingly manufactured to serve others’ ends. If desire is the engine of our striving, we are in danger of running on fuel that corrodes us. Read more »

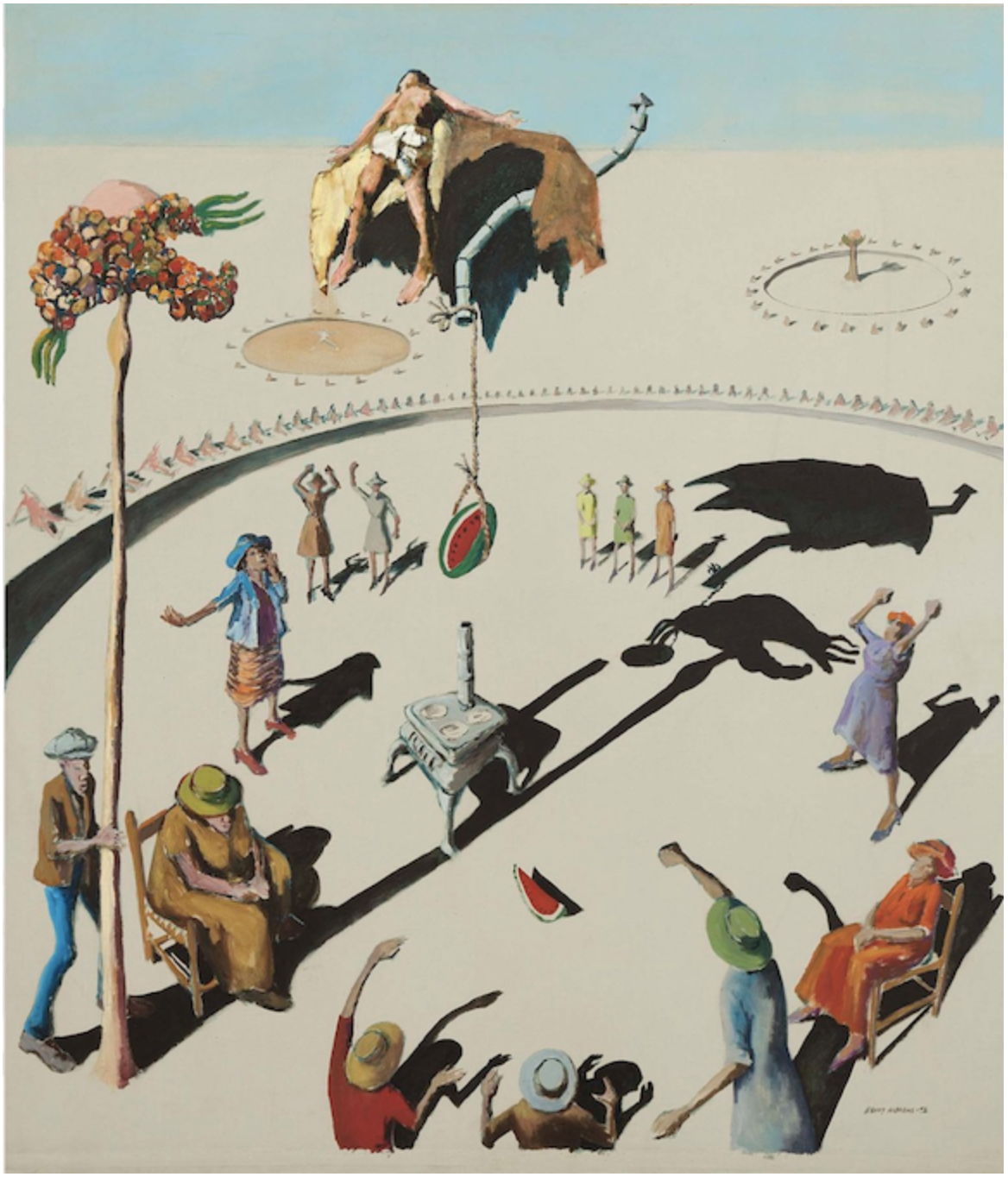

Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Tim Sommers

The ends don’t justify the means. Right? But then what does?

Utilitarians say that, of course, the ends justify the means. If the ends can’t justify the means, then nothing can. Utilitarianism is built on the twin pillars of welfarism and consequentialism.

Consequentialism is the view that the morally right thing to do is whatever has the best consequences.

Welfarism is the view that the only thing intrinsically valuable is human happiness, welfare, well-being, having their desires fulfilled, flourishing, or the like.

Utilitarianism calls whatever it is exactly that matters in terms of human good (happiness, having your preferences fulfilled and flourishing are not exactly the same thing) utility. Utility is a technical term for whatever it is that is intrinsically valuable – which has something to do with human happiness

Powerful intuitions support this combination of consequentialism and welfarism. From a consequentialist perspective, to deny the truth of utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that sometimes, given the choice, we should find the worse morally superior to the better. Specifically, that we should sometimes do the thing that has worse consequences – even when we could have done something with better consequences. From the welfarist perspective, to deny utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that we must, at least sometimes, intentionally do things that make everyone overall less happy when we could have done something that would have made people overall more happy.

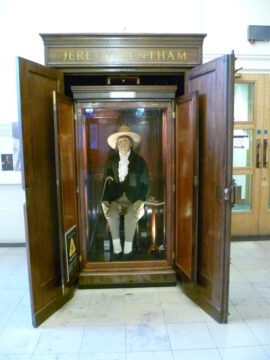

“During much of modern moral philosophy the predominant systematic theory has been some form of utilitarianism,” John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice. “One reason for this is that it has been espoused by a long line of brilliant writers who have built up a body of thought truly impressive in its scope and refinement…Hume and Adam Smith, Bentham and Mill, were social theorists and economists of the first rank; and the moral doctrine they worked out was framed to meet the needs of their wider interests.”

However, all the classical utilitarians had in common that they used two very different kinds of argumentative strategies to bolster the view: one we might call the negative or downward approach, the other, the positive or upwards argument. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

Mathematics is an inexhaustible subject. Every time you think you’ve mined out a vein, you hit a new gem. There is no clear reason why this should be true, but all evidence shows that it is mathematics all the way down [1].

I once saw a talk by a mathematician near retirement who had made numerous influential discoveries over the years. The recurring theme of the talk was how, time after time, he finally understood everything about his favorite corner of mathematics. The joke, of course, was that each new discovery revealed how his previous “complete” understanding still overlooked interesting and important things.

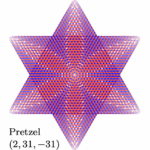

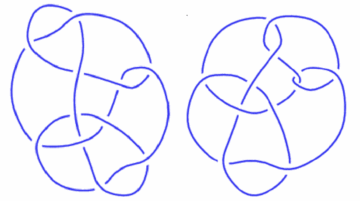

An excellent example of this phenomenon is knot theory. This is the mathematics of figuring out how to distinguish different knots. Two knots could look very different, but could turn out to be the same after some manipulation. Or not! For example, to the right are two knots created by Conway and by Kinoshita-Terasaka. It turns out to be extraordinarily difficult to figure out if they are the same knot or not.

This is one of those kinds of research that politicians and know-nothings love to sneer at. It sounds stupid, trivial, and of no use to anyone. However, if you’re one of those who care about real-world applications, the mathematics of knot theory plays a role in string theory, protein folding, quantum computing, and more.

But if you’re one of those who find math interesting for its own sake, then you’ll be glad to learn that knot theory is a rich vein of mathematics that continually reveals deep, beautiful, and interesting new discoveries. In this essay, I thought I’d share yet another new discovery in knot theory. Longtime readers of 3QD won’t be surprised: we’ve talked about knots many, many, many times over the years. Read more »

Common, simple thoughts are hard to place in

deep context as they rush our minds and hold them fast.

So,

we don’t look in,

but out,

around, and

past.

Too small to be big,

small-thoughts squeeze

between lines

suggesting,

hinting,

asking,

& telling

as the tale unfolds.

To big to be small,

they come off as incidental

while holding a universe

in their grasp.

We wander half-awake through days ignoring

the stupendous humble things each day contains:

—FuturePresentPast & WhatRemains,

the One-Thing

Jim Culleny

7/23/21-Edited 9/28/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Scott Samuelson

When it comes to the subject of help, contemporary philosophy is rarely helpful. Its discussions tend to revolve around things like if it’s morally acceptable to buy a cappuccino when children are starving somewhere, or what percentage of your income you’re entitled to keep, or (I’m not kidding) how much donating money harms you and the extent to which that harm should be balanced against the help you’re obliged to maximize. If you’re the kind of person who thinks that moral reasoning is an extension of balancing your checkbook, a rich literature awaits.

Floating in the background of these discussions is the idea that our current economic system is unjust. A lot of people agree with that. I agree with that. But I have my doubts that the best way to help the situation involves composing a scathing piece of theoretical Marxism, much less publishing a journal article for your career advancement that scolds its readers for having spent some of their graduate-school stipend at Starbucks.

We need real help with the quandaries we have about help. As far as politics goes, we wonder about what we can do to improve the situation and worry about if the backlash to our efforts will render them counterproductive. Even more often, we wonder about how to help the people we care about. When should I let things play out? When do I intervene? What can I even do? How can I do it? Also, how can I get my partner to stop constantly trying to fix me? Wait, do I need help?

Sometimes a situation presents itself where help is needed and help is wanted and help would clear up the problem and you know what’s needed and you have what’s needed and you’re in a position to give it. The norm is usually more complicated.

Let’s say you have a brother. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

I recently went to see a painting that I love but hadn’t seen for about 40 years, Samia Halaby’s Boston Aquarium. It had been important to me when I was an undergrad at Indiana University in the 1980s, and I’d thought I might never see it again in person. When I learned that it was on display at Indiana University’s art museum, the Eskenazi Museum of Art, I was incredulously joyful at the prospect of immersing myself once again in its color and light.

Boston Aquarium is a large abstract painting (72 1/4 × 95 3/4 inches, oil on canvas). Halaby completed it in 1973. I remembered it for years as a dark painting overall, but its darkness is suffused with light and color. When I first saw it in the mid-1980s, I was studying astrophysics. Although the universe is mostly dark, light—ancient light in particular—is a central concern of astronomy, and the sense of rays of light in the painting was one of the things that drew me to it.

I remember visiting it frequently and losing myself in its shapes and colors, but it’s difficult to remember, this many years on, what exactly I saw in it. I think the helicoid shapes reminded me of the curves of the conic sections I learned about in my calculus classes. Some of the arrangements of colors in the painting might have been evocative of stellar spectra. Overall the painting gave me an expansive sense of moving through vast spaces.

∞

At some point I lost track of Boston Aquarium. I moved away from Bloomington briefly after I graduated, and when I returned, I couldn’t find it at the art museum. (I did find another painting by Halaby in a similar style, Red Green Steel, which I also loved.) In the early 2000s, I wrote to the art museum to ask about it and received the disappointing news that there was no record of the university owning it. I assumed it had been on loan when I’d seen it in the 1980s. Read more »

by Thomas Fernandes

A rodent with orange teeth and a paddle tail comes across a river. He tries to build a lodge but the stream is too low so he grunts, “Dam!”.

While the pun captures the beaver in miniature, the real story lies in the web of relationships that shapes it and the ecosystem in return. To see how deeply a species is shaped by these relationships, it helps to look first at its body.

This 20 kg semi-aquatic mammal is an extraordinary swimmer. It uses its tail as a rudder and webbed hind feet to glide efficiently through water. It can hold its breath for up to fifteen minutes thanks to a suite of cardiovascular adjustments known as the diving reflex. This reflex slows the heart and redirects blood flow to vital organs, a trait shared with seals and penguins.

Their fur is equally adapted: a very soft underlayer traps air and provides insulation with an incredibly high hair density (ten times the density of human hair), while a covering layer of longer guard hairs repels water, a property further enhanced by oil secretions that act like wax. Even their eyes are specialized for underwater vision, equipped with a nictitating membrane (a third transparent eyelid) that functions as natural goggles underwater.

By observing their bodies, it would be tempting to think nutria are close relatives. After all, they share water-repellent fur, webbed feet and even a diving reflex.

But looks can be deceiving: beavers and nutria split from a common ancestor 50–60 million years ago, long before humans and chimps parted ways just 7 million years ago. This is a case of convergent evolution, showing that similar environmental pressures can produce similar forms even in lineages with very different histories. Yet such adaptations are always built on top of existing genetic heritage. To understand what truly set beavers apart, we need to turn away from look-alikes and toward their real cousins in the desert. The closest living relatives of beavers are North American desert-dwelling burrowers. Examples include kangaroo mice and pocket mice. Despite their vastly different appearances, observing their behavior reveals deep evolutionary continuity. Read more »

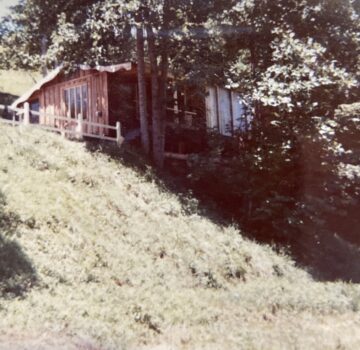

by Mike Bendzela

You could tell we were on the last leg of our journey to Kentucky when, after we had crossed the Ohio River at Portsmouth and entered the curvaceous roads of the Appalachian Plateau, the puking began. At the time, we were a family of six crammed inside Dad’s 1963 white Ford Fairlane two-door sedan. Mom had one toddler brother up front, and Sis and I watched the other little brother in the backseat. It was exciting to go from the Great Plains cornfields ambience of the highway south of Toledo to the seemingly endless rugged hills below Columbus, but that excitement turned to horror once the back-and-forth, up-and-down, start-and-stop driving commenced on the back roads of Carter County, Kentucky. Mom had brought along a Hefty trash bag for just such an emergency, and as we kids went pale and cold in the backseat one by one, we took turns passing the bag among ourselves and heaving our roadside stop dinners into it.

Thus begins the story of this northern city-slicker’s romance with the American South, a halting, stop-and-go affair that has lasted decades and should, I hope, continue to the end of this life. It was during these trips to Eastern Kentucky in my boyhood that I realized I have a throbbing mass of neurons in my brain that pines for a long lost, agrarian past. This is a self-generated illusion, of course, and I’ve always known that, but it hasn’t stopped me (nor should it stop anyone) from trying to revive, recreate, and reconstruct this remote and vital aspect of North American history. Read more »

by Azadeh Amirsadri

I was an English as a Second Language teacher in a suburban high school in VA from 1997 to 2002. I taught levels 1 and 2, beginners and intermediate levels, and had a total of five classes each year. My students were from all over the world, and my five years with them were some of the best teaching experiences I have had. Every day of the week, we would gather as a family, joined by our otherness, and go through school and life together.

On the first day of school, I would go over their schedule and show them where their classes were, since they were usually grouped together in physical education or electives, and take them to their lockers so they could practice opening and locking them, an activity that would sometimes take the whole period. I would also take them to the cafeteria to show them about getting lunch, avoiding pork products for the Moslem kids, if they chose to, and get an alternative lunch. The county had little pink cards with the picture of a pig on them that were put next to the pork products, so that helped them. They had to memorize their student ID to pay for the food at the end of the line, and I‘d remind them that they didn’t have a lot of time for eating and cleaning up afterwards, 30 minutes from start to finish, and some lines were longer than others, so maybe bringing lunch from home could help them not rush as much. However, the sight of school pizza, fries, and chocolate milk was too much of a competition with lunch from home.

Students would sometimes arrive at any time in the middle of the school year after getting tested at a central registration center in the county, and slide right into any level they tested in. Everyone in class, except two kids, had someone who spoke their language in the school, and when they landed in my class, they had someone who could show them the ropes of an American high school.

There was a girl from Cameroon who didn’t have anyone else in class who spoke French, so I would speak to her when she needed help, and the others would tease her that she was my favorite. She was a bit older than the others, but not very mature, and would get into arguments with them. I was fascinated by how the students argued with their very limited English in level 1, using the profanities they had learned and knowing it wasn’t a nice thing to say, but not having any other words to convey their anger and their dislike of each other during fights. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

On June 21st, 2025, President Trump ordered a series of strikes on Iran aimed at ending their nuclear program. The Iranians had maintained their legal right to develop a peaceful, domestic nuclear program. After Trump pulled the US out of the JCPOA (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) negotiated during the Obama administration, he claimed he could cut a new deal with the Iranians quickly. After several false starts, he instead joined in on the violence started by the Israelis earlier in June in their obvious effort to distract from the ongoing acts of genocide in Gaza.

The group probably most excited by Trump’s actions are his far right white evangelical followers. They know that this very well could cause a chain reaction of violence across the region and possibly the world. They are hoping for and counting on it with glee in their hearts. They view it through a cult-like belief in the End Times. In their fevered imaginary, the End Times are a kind of ultimate victory that will prove their righteousness. They want nothing more than to watch their enemies burn from their clouds on high. But what if they are wrong about this being the start of the apocalypse? I argue, that, in fact we already live in a post-apocalyptic world and have done since 1945.

Definitions matter of course, but definitions can change with the historical context. We like to pretend words’ meanings are stable across human history and experience, but it’s just not so. Today, the term apocalypse has become a bit secularized and unmoored from its religious origins. The original meaning connected to the modern understanding of the term comes from Judaism. The term apocalypse was a genre of literature that followed from their Babylonian Exile of the 6th century BCE. The term means “revelation” in the Greek. It also denoted a change in circumstances and context, a historical break. The dreams or visions experienced by the early prophets of Judaism represented the meaning of the word during that era. The term that relates to God destroying the world, but saving his followers is more accurately apocalyptic eschatology. Revelation was not just about the world inevitably ending but it can refer to prophetic revelations about the “end of days.” That could denote an end or a new beginning. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

The late Robert F. Kennedy, who ran for President in 1968, could be considered a great man and even more commendably, a good man. It wasn’t always so. As a young ambitious lawyer he served under Joseph McCarthy during the hearings meant to weed out communists from American politics. Those hearings ruined many a life and are a stain on American history. He was an early supporter of the Vietnam War, perhaps our most ill-considered and violent venture overseas. In short, he was as misguided as a young man as his now seventy-one-year-old son RFK Jr is as an old man. The big difference is that the father evolved over the years from vast experience and from the terrible loss when his own brother was assassinated. He went from a cocky, overly ambitious lawyer to a compassionate man tempered by pain.

His son RFK Jr has traveled the opposite life arc. He began his career as a promising and effective environmental lawyer and in a story worthy of Greek tragedy, took on the arrogance of an Agamemnon or an Icarus. If you like the classics, you’ll recall that Agamemnon, the protagonist in a play written by Aeschylus, committed a great act of hubris. He sacrificed his own daughter Iphigenia to get favorable winds for his warships on their way to Troy.

RFK’s act of hubris is assuming he has the background and ability to manage something as massive and complicated as Health and Human Services, by far the biggest budgeted department in the US government, weighing in at $1.6 trillion. Its budget dwarfs the Department of Defense. Health and Human Services has 80,000 employees and oversees some of our most important agencies including The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In many ways choosing that secretary should a be a president’s most important decision. The effectiveness of the CDC alone may well determine whether the next pandemic is stopped in its tracks or kills millions of people. The FDA works hand-in-hand with the CDC in determining which vaccines can and can’t be released, which medicines are ready for market, and how to keep our food supply safe. In other words, the person in charge of all this should be very good at managing money, tens of thousands of people from diverse professions, and have either a strong science background or at least the humility to defer to those who do. Read more »

by Alizah Holstein

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

I was startled by the unanticipated intimacy of this conversation (his conversation, really, seeing as I said little) and I was perhaps a little aware of being alone in my home and of having tied my dog outside. But if my hackles were up it was only very slightly, and in their place curiosity had begun doing its work. Why was he telling me all about his private life? The writerly instinct had kicked in; the man had leaped cleanly from contractor to material.

I started to think about where we get material. Sometimes, material is the byproduct of effort. But other times we run into it as if by chance. In the last few years, I have started taking notes on the way people talk. There’s a woman I knew who threw the expression “madder than a wet hen” into every conversation; and a man who repeated the same few sentences so many times that I wrote them down out of the sheer need to occupy myself as he spoke. Read more »

Two ceramic swans my wife bought cheaply at a flea market somewhere. They might be tea-light holders. Or something like that. I like them.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

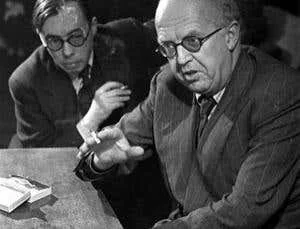

by Steve Szilagyi

Henry James once observed that Robert Louis Stevenson “wrote with a kind of gallantry — as if language were a pretty woman.”

C.P. Snow (1905–1980) did not write like that. Pretty did not seem to enter any area of his work. The author of the famous essay The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (1959) and the eleven-book cycle of novels known as Strangers and Brothers was, in his physical person, emphatically not pretty. As he approached the end of his life, he came more and more to resemble a pink, pointy-headed Patrick Star from SpongeBob SquarePants—decidedly dour, with National Health panto glasses somehow attached to his face.

If Snow wrote with any kind of gallantry, it was the solemn courtesy you would show a group of serious men seated around a table in an oak-paneled boardroom. His prose was careful, deliberate, and capable of discovering fine distinctions in faces, morals, and motives. His essays and novels were best sellers in Great Britain and the United States, and he won awards and honors for his writing. The BBC even made Strangers and Brothers into a thirteen-part series that no one liked.

In the 1960s, The New York Times referred to him as “the most eminent living English author” at a time when no less than Evelyn Waugh, Iris Murdoch, and Graham Greene were all busily writing away. Yet no author of similar stature in the 20th century has been more thoroughly and publicly excoriated for being slow, dull, and unreadable. Not even Gertrude Stein! Read more »