by Tim Sommers

The ends don’t justify the means. Right? But then what does?

Utilitarians say that, of course, the ends justify the means. If the ends can’t justify the means, then nothing can. Utilitarianism is built on the twin pillars of welfarism and consequentialism.

Consequentialism is the view that the morally right thing to do is whatever has the best consequences.

Welfarism is the view that the only thing intrinsically valuable is human happiness, welfare, well-being, having their desires fulfilled, flourishing, or the like.

Utilitarianism calls whatever it is exactly that matters in terms of human good (happiness, having your preferences fulfilled and flourishing are not exactly the same thing) utility. Utility is a technical term for whatever it is that is intrinsically valuable – which has something to do with human happiness

Powerful intuitions support this combination of consequentialism and welfarism. From a consequentialist perspective, to deny the truth of utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that sometimes, given the choice, we should find the worse morally superior to the better. Specifically, that we should sometimes do the thing that has worse consequences – even when we could have done something with better consequences. From the welfarist perspective, to deny utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that we must, at least sometimes, intentionally do things that make everyone overall less happy when we could have done something that would have made people overall more happy.

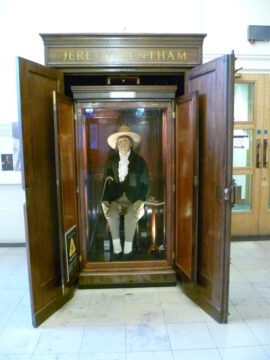

“During much of modern moral philosophy the predominant systematic theory has been some form of utilitarianism,” John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice. “One reason for this is that it has been espoused by a long line of brilliant writers who have built up a body of thought truly impressive in its scope and refinement…Hume and Adam Smith, Bentham and Mill, were social theorists and economists of the first rank; and the moral doctrine they worked out was framed to meet the needs of their wider interests.”

However, all the classical utilitarians had in common that they used two very different kinds of argumentative strategies to bolster the view: one we might call the negative or downward approach, the other, the positive or upwards argument. I have mentioned the positive argument in an earlier column on weighing lives. One iteration of it goes like this.

(1) Everyone’s welfare is equally valuable.

(2) Everyone’s welfare is intrinsically valuable.

(3) We should always prefer more of what is intrinsically valuable to less.

(4) Therefore, we should always maximize welfare.

I will return to this argument, and weighing lives, at some point. But I actually find the negative argument for utilitarianism to be more persuasive so I thought I would go there today.

According to utilitarians, there’s only one moral rule. “Always do whatever maximizes utility.”

A straight-forward approach, to keep it simple, would be to offer and defend one or more moral principles, other than the principle of utility. When I ask students to name moral rules, the top three answers are don’t kill, don’t lie, and don’t steal. So, let’s focus on this rule, “Don’t kill people.” Let’s take suicide and euthanasia off the table and say, “Don’t kill other people.”

Do you believe that rule? What about self-defense? The death penalty? Killing combatants during a just war? Even if you think all wars and capital punishment are immoral, self-defense alone might suggest we amend the principle again, this time to “Don’t kill innocent people.”

The first thing to notice is that even if that takes care of the death penalty and fellow combatants in just wars, it is not obvious that self-defense requires wrong-doing on the “aggressors” part. You may have the right to use lethal force to protect yourself from imminent death even if the other party is not morally culpable. Suppose you have been thrown down a well and survived, but now they are going to throw another person on top of you and that will finish you off. If you have a very large gun so that you can blast anyone they throw into many small harmless-sized pieces, are you justified in killing the deadly nonaggressor to save yourself? (Yes, in case you haven’t encountered this before, ethics classes often rely on surprisingly violent examples.)

The second thing to notice is that we can let “innocent” be a stand-in for “whenever or whatever we think it is a morally unacceptable time to kill someone,” otherwise it is just a dodge. And there are other exceptions.

What about killing to defend others or some very bad future harm? What about sacrificing the life of one conjoined twin to save the other? Or many less exotic forms of potentially deadly triage? Do late term abortions count as killing innocent person?

What about the trolley problem? Stripped of all the window dressing, the question is, all other things being equal, should we be willing to kill one person to save five people who would otherwise die (but not have been killed by you). If we should save the five – and most of my students think that we should – why not one to save four? Or two? Here’s a possibility. What we ought to do in trolley-like problems is maximize lives saved (to the extent that lives is a plausible stand-in for welfare here). In other words, we kill or save according to what maximizes utility.

Similarly, in war, and others kinds of defense cases, in triage cases, really, in all cases, the best rule is not don’t kill, followed by some qualifications and exceptions. The best rule is kill when it maximizes utility and refrain when it does not.

With the exception of the principle of utility, utilitarians say, moral rules are more like rules of thumb or shortcuts to get the right answer. In the vast majority of cases, the right thing to do is to refrain from killing anyone. But in problematic cases the answer always is: do whatever maximizes utility.

Perhaps, if we spent more time on it, a critic of utilitarianism would reply that rules like “don’t kill” could be sufficiently fleshed out to be accurate without just being another way of saying maximizing utility. A more common approach is to confront utilitarians with counterexamples that show that maximizing utility can lead to terrible, and implausible, moral decisions.

Here’s one. Suppose you check into a hospital for a routine, very safe procedure, but the doctors discover you are a donor match with five patients on the verge of death. Utilitarianism seems to license sacrificing one – namely you – by redistributing your organs, in order to save five. But that can’t be right.

Sometimes utilitarians simply bite the bullet and say that our everyday intuitions about right and wrong sometimes lead us astray and the moral implications may shock us, but that does mean they are false. Rarely, in the organ transplant case, however.

A more promising approach would be to say that this example is too quick. Maybe, killing one to save five is right in some kinds of all things considered situations, but just take one feature left off here. What would happen to hospital admissions if people knew that an inadvertent donor match could cost you your life? How many people might die as a result of a general reticence to seek early medical intervention?

We haven’t settled anything, of course. The point is that one plausible route to utilitarianism is to see that moral rules other than the principle of utility, when properly qualified, turn out to be the principle of utility applied to a specify area, e.g. killing, but amounting to the same.

Arguing about fringe cases, like the organ donor, one, is illuminating, but probably not the best way forward. What’s missing from utilitarianism? That’s the real question.

Here are a couple of plausible candidates. Utilitarianism doesn’t care about equality, in fact, it doesn’t care about the distribution of happiness at all. Finally, utilitarianism leaves no space for people have the freedom to make moral choices – even including choices that are wrong. There’s no freedom without the freedom to be wrong.

(For all things utilitarian, I cannot recommend highly enough Utilitarianism.net. Accurate, clear, and put together by the leading utilitarians. Also, for accurate information on almost any topic (including this one) in philosophy see the great Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.)