by Bill Murray

After three years of pandemic and a year of war, could things be about to get better? With the defeat of Jair Bolsanaro in Brazil, President Xi’s Covid problems in China and President Putin’s all-around debacle of destruction in Ukraine, could the worldwide wave of authoritarianism be breaking?

If so, the incoming Republican House could be the rump of ugly populism and, for all that that’s fun to write, it could go out kicking up more trouble than anyone wants to see. This Congress will legislate the future of the country until a new president is elected. Hoo boy, how much could they undo in two years?

If last week gave us a preview of the next two years in the U.S. House, they promise to be sort of like watching a YouTube lecture at 2x speed, choppy and distracting. But as the House Republican caucus settles in to comb through the life of Hunter Biden, what might happen in the rest of the world? Undreamt of things, probably. All over the place.

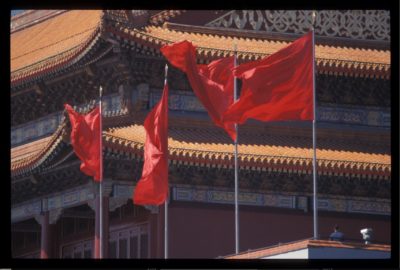

We won’t have to wait too long to learn one thing: the true extent of China’s Covid problem. That should become clearer over the next several months. We know that as it is, untold numbers of rural Chinese people, surely millions, languish in a health care system with only the most basic resources. We also know that when the going gets tough, government controlled data gets scarce, and worryingly, that is precisely what we are seeing now. Read more »

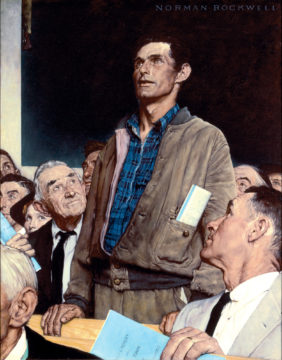

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.)

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.) Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window.

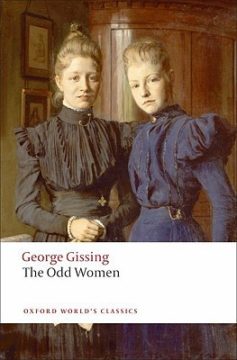

Sughra Raza. Cactus In My Window. This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.