by Varun Gauri

At the University of Chicago, I majored in an interdisciplinary concentration most easily characterized as Great Books. I studied with an Indian poet, a Japanese postmodern literary critic, and an historian who admired Michel Foucault, but my most influential professors were men influenced by Leo Strauss, including Allan Bloom, Joseph Cropsey, Leon Kass, and Nathan Tarcov, a smart and stirring group of teachers. They were also politically conservative, though I was too politically naive, and too flattered by their approval, to notice. Junior year, invited to speak about my selected Great Books at a humanities conference, I talked about the changing valence of cleverness in Homer, Aristotle, and Descartes. The conference took place in the context of the canon wars, and when during Q&A people asked me if there were women or non-European authors on my list, I offhandedly threw out a few names. A mentor would later compliment my disarming ingenuousness.

Some of the professors regretted their Eurocentrism but felt helpless to correct it, given their linguistic limitations. Others wore it proudly. Most notoriously, Saul Bellow supposedly said, “When the Zulus produce a Tolstoy, we will read him,” a position that Charles Taylor would take down in “The Politics of Recognition” (though, sadly, after I graduated). Even in the 1980s, though, many of us could tell there was something odd about the idea of a literary or philosophical canon in a multicultural society and long globalized world of letters. For what it was worth (and it wasn’t much, since canon expansion grows out of the same impulse as canon construction, tokenism in response to fetishism, still the scorekeeping), I made a point to include Hannah Arendt and The Mahabharata on my lists.

Looking back, I’m stunned not so much by the program’s male Eurocentrism, which was advertised (caveat emptor), but its insularity. Why did no one tell me about Becker’s Denial of Death, whose reinterpretation of psychoanalysis would have informed my essay on heroism? I read Nietzsche’s takedown of Christian morality but had no idea that Dewey had developed a more American and optimistic response to the death of God. I wish I’d known about Charles Taylor’s work on moral horizons, Margaret Atwood’s world-building, Tagore’s cosmopolitanism. The Great Conversation, it turns out, is much wider than I knew. It is, in fact, still going on. I might even have been a participant, in my own way, not just an eavesdropper. Read more »

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

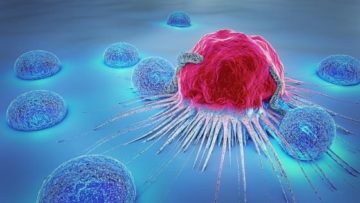

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes. Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way.

A few months ago, I wrote about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Spring and how his focus in this book is the examination of two worlds: the physical world that exists apart from us (the outside world), and the world of meaning and significance that is overlaid on top of this world through language and consciousness (the inner world). Knausgaard’s main goal seems to be to shock us out of our habitual, unreflective existence, and to bring about an awareness with which we can experience our lives in a different way.