by Akim Reinhardt and GPTChatbot

A couple months back, I wrote an open letter to fellow professors. Don’t panic, I said. Yes, new crops of student plagiarism bound are sprout in the fertile fields of free, online AI software. But it’ll be alright. Here’s how to adjust.

A couple months back, I wrote an open letter to fellow professors. Don’t panic, I said. Yes, new crops of student plagiarism bound are sprout in the fertile fields of free, online AI software. But it’ll be alright. Here’s how to adjust.

Then it occurred to me: Why should students have all the fun? I can now plagiarize just as easily as they can. So I decided to have the GPT Chatbot write my monthly 3QD column and see what we get.

First I established that the chatbot could identify 3QD, and me as one of its contributers. It thinks I’m a writer (yes), journalist (eh), and editor (not really). No mention of me being a historian, a professor, or man of dubious character. It claims I’ve written for the Washington Post and the Guardian; the truth is I’ve been interviewed by those news outlets, but never written for them.

Then I asked it to write a thousand word essay. Not counting its disclaimer, the GPT Chatbot pumped out just over half that (590 words). That essay follows. I graded it and have marked it up [my comments are red and in squared brackets, like so]. Let’s see how we did.

Prompt: Write a 1000 word essay in the style of 3 Quarks Daily writer Akim Reinhardt

Response: Note: As an AI language model, I can generate text in the style of Akim Reinhardt, but the content and opinions expressed in the essay are purely generated by AI and do not reflect the views of any human writer.

The Uncertain Future of Democracy in the United States

The United States of America has long been regarded as a beacon of democracy in the world, a shining example of a free and open society that values individual rights and liberties [By some; others have long criticized it for not living up to its vaunted values. Also, a punchier lede would help]. However, recent years have seen a troubling erosion of democratic norms and institutions in the country, raising questions about the future of democracy in the US. [Does it represent an absolute descent or a regression to the norm? In retrospect, 1968–2000 may have been a highpoint for U.S. democracy, preceded and now proceeded by numerous attempts, both legal and corrupt, to limit the franchise and thwart the will of the majority.] Read more »

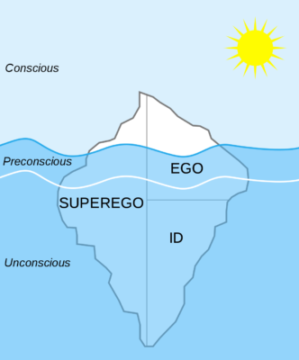

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist  So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which

So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which  Ntozake Shange, right, with Janet League in her play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” 1976. Bettmann/Getty Images

Ntozake Shange, right, with Janet League in her play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” 1976. Bettmann/Getty Images

obscure, often extraordinary abilities of animals and plants. Today, let’s look at a few more:

obscure, often extraordinary abilities of animals and plants. Today, let’s look at a few more:

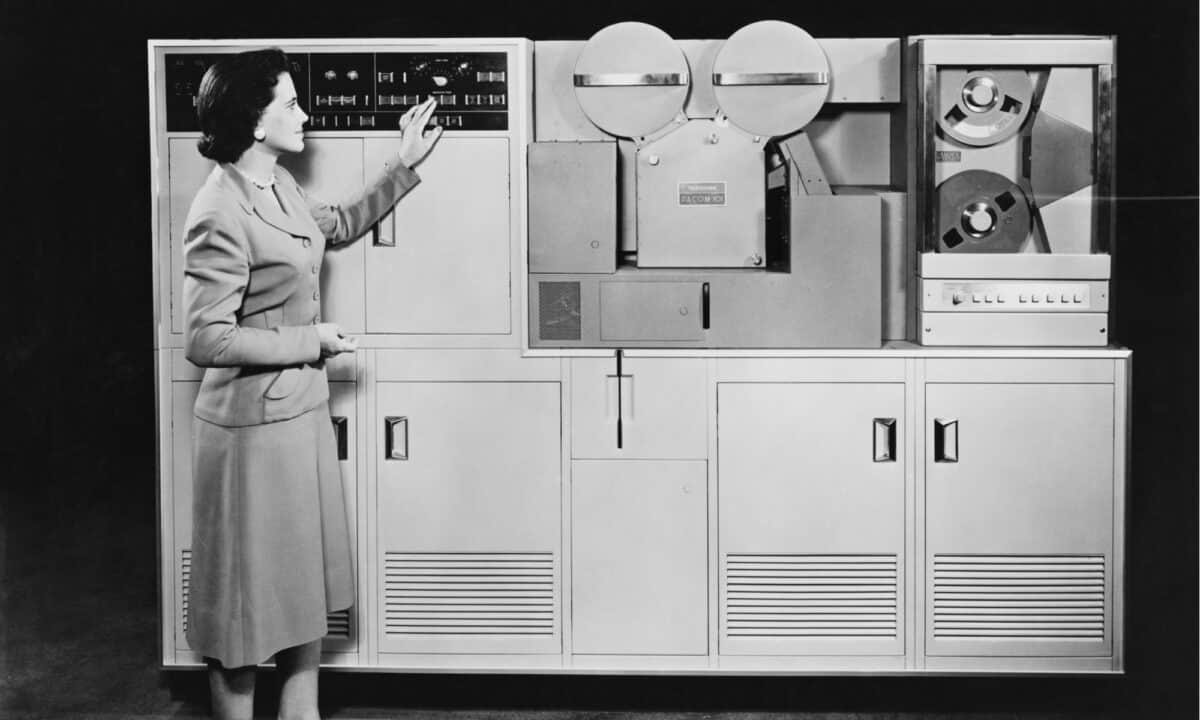

reading “GPT for Dummies” articles. Some were more useful than others, but none of them gave me what I wanted. So I started poking around in the technical literature. I picked up a thing or two, enough to issue a working paper,

reading “GPT for Dummies” articles. Some were more useful than others, but none of them gave me what I wanted. So I started poking around in the technical literature. I picked up a thing or two, enough to issue a working paper,  Google the phrase “is it time to care about the metaverse?” and there are a wealth of articles, mostly claiming that the answer is yes! Are they right?

Google the phrase “is it time to care about the metaverse?” and there are a wealth of articles, mostly claiming that the answer is yes! Are they right?  Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism).

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism). Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.