by Tim Sommers

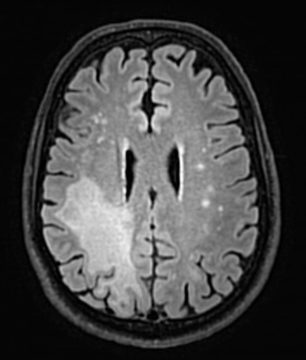

One thing that Elon Musk and Bill Gates have in common, besides being two of the five richest people in the world, is that they both believe that there is a very serious risk that an AI more intelligent than them – and, so, more intelligent than you and I, obviously – will one day take over, or destroy, the world. This makes sense because in our society how smart you are is well-known to be the best predictor of how successful and powerful you will become. But, you may have noticed, it’s not only the richest people in the world that worry about an AI apocalypse. One of the “Godfathers of AI,” Geoff Hinton recently said “It’s not inconceivable” that AI will wipe out humanity. In a response linked to by 3 Quarks Daily, Gary Marcus, a neuroscientist and founder of a machine learning company, asked whether the advantages of AI were sufficient for us to accept a 1% chance of extinction. This question struck me as eerily familiar.

Do you remember who offered this advice? “Even if there’s a 1% chance of the unimaginable coming due, act as it is a certainty.”

That would be Dick Cheney as quoted by Ron Suskin in “The One Percent Doctrine.” Many regard this as the line of thinking that led to the Iraq invasion. If anything, that’s an insufficiently cynical interpretation of the motives behind an invasion that killed between three hundred thousand and a million people and found no weapons of mass destruction. But there is a lesson there. Besides the fact that “inconceivable” need not mean 1% – but might mean a one following a googolplex of zeroes [.0….01%] – trying to react to every one-percent probable threat may not be a good idea. Therapists have a word for this. It’s called “catastrophizing.” I know, I know, even if you are catastrophizing, we still might be on the brink of catastrophe. “The decline and fall of everything is our daily dread,” Saul Bellow said. So, let’s look at the basic story that AI doomsayers tell. Read more »

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

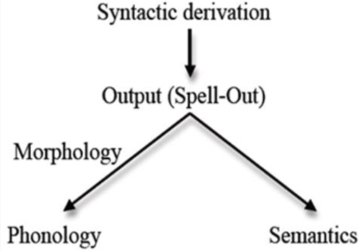

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since