by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

And You May Find Yourself Living in an Age of Mass Extinction…. So begins Timothy Morton’s latest book, All Art is Ecological.

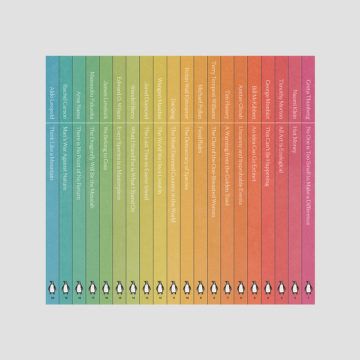

Published as part of Penguin’s new Green Ideas Series, this slim paperback sits alongside nineteen other works of environmental writing. From farmers and biologists to artists and philosophers, spanning decades, the books offer a wide range of perspectives, which Chloe Currens, the editor of the series, says serves to present an evolving ecosystem of environmental writing.

Along with classics like Masanobu Fukuoka’s The Dragonfly Will Be the Messiah and Rachel Carson’s The Silent Spring; there is the work of many contemporary thinkers, such as Greta Thunberg’s No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, Amitav Ghosh’s Uncanny and Improbable Events, and George Monbiot’s This can’t be happening.

I wanted to read them all—but I started with Timothy Morton, who has been called “the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene.” A big fan of his writing, I think Timothy Morton is pretty much the most exciting thinker alive. I was, therefore, not surprised to find myself challenged from the very first sentence.

What does this mean exactly: You MIGHT find yourself living in an age of mass extinction?

Why the subjunctive? Read more »