by Jeroen Bouterse

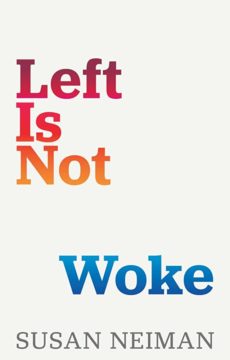

At the core of Susan Neiman’s new book Left is not Woke, which is an attempt to sever what she sees as reactionary intellectual tendencies from admirable progressive goals, is the idea that for progressive values to be sustainable, their roots in the philosophy of the European Enlightenment need to be recognized and nourished. “If we continue to misconstrue the Enlightenment”, she says, “we can hardly appeal to its resources.”

At the core of Susan Neiman’s new book Left is not Woke, which is an attempt to sever what she sees as reactionary intellectual tendencies from admirable progressive goals, is the idea that for progressive values to be sustainable, their roots in the philosophy of the European Enlightenment need to be recognized and nourished. “If we continue to misconstrue the Enlightenment”, she says, “we can hardly appeal to its resources.”

The misconstruction that Neiman alludes to is a view that sees Enlightenment thought as deeply hypocritical: talking the talk of liberty and equality, but guilty in practice of systematic motivated reasoning that at best failed to question, and at worst actively contributed to racist and sexist ideologies justifying oppression by European men. Her double thesis is that this is an inaccurate view of enlightened thought, and that bad-mouthing the Enlightenment in this way leads us to discard indispensable tools for combating injustice in the present.

For Neiman, this error defines wokeness: ‘woke’ escalates a concern for inequalities of power and for historical injustice into the belief that history is a matter of power only. “Anybody who says the word ‘humanity’ wants to deceive you” sums up the cynicism that Neiman sees herself as being up against. It is a quote from the Nazi theorist Carl Schmitt, who in Neiman’s narrative serves as a bridge of sorts between the 18th-century counter-Enlightenment, and a post-WW2 anti-humanism that got us Foucault and left-wing “tribalism”. It is an uneasy grouping from the start, but this could be a sign that an interesting argument is coming up. Read more »

I first heard “The Blundering Generation” in the 1990s when I was taking a course on Civil War history. As my professor explained, the early 20th century saw a new cohort of historians who no longer personally remembered the war and debated anew the nature of its origins. They were trying to move past the earlier, caustic interpretations of Northerners and Southerners who openly blamed each other, the former decrying the Southern “slaveocracy” and the latter bemoaning the “war of Northern aggression.” So instead, these thinkers at the vanguard of historical study decided to blame everyone. Or no one.

I first heard “The Blundering Generation” in the 1990s when I was taking a course on Civil War history. As my professor explained, the early 20th century saw a new cohort of historians who no longer personally remembered the war and debated anew the nature of its origins. They were trying to move past the earlier, caustic interpretations of Northerners and Southerners who openly blamed each other, the former decrying the Southern “slaveocracy” and the latter bemoaning the “war of Northern aggression.” So instead, these thinkers at the vanguard of historical study decided to blame everyone. Or no one. Sughra Raza. Santiago Street Color, Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Santiago Street Color, Chile, November 2017. Spanning just shy of a thousand years, al-Andalus or Muslim Spain (711-1492), has a riveting history. To picture the Andalus is to imagine a world that gratifies at once the intellect, the spirit and all the senses; it has drawn critical scholars, poets and musicians alike. Barring cycles of turbulence, it is remembered as an intellectual utopia, a time of unsurpassed plentitude and civilizational advancements, and most significantly, as “la Convivencia” or peaceful coexistence of the three Abrahamic faiths brought together as a milieu. Al-Andalus was a syncretic culture shaped by influences from three continents— Africa, Asia and Europe – under Muslim rule. This civilization came to be known as a golden age for setting standards across all human endeavors, a bridge between Eastern and Western learning, sciences and the fine arts, between the public and private, native and foreign, sacred and secular— a phenomenon hitherto unknown in antiquity. The decline and eventual collapse of al-Andalus is no less of a legend; it is a history of in-fighting and brutal intolerance perpetrated throughout the three centuries of the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) with ramifications to witness in our own times. The stark contrast between the Convivencia and the Inquisition makes al-Andalus a poignant story of reversals.

Spanning just shy of a thousand years, al-Andalus or Muslim Spain (711-1492), has a riveting history. To picture the Andalus is to imagine a world that gratifies at once the intellect, the spirit and all the senses; it has drawn critical scholars, poets and musicians alike. Barring cycles of turbulence, it is remembered as an intellectual utopia, a time of unsurpassed plentitude and civilizational advancements, and most significantly, as “la Convivencia” or peaceful coexistence of the three Abrahamic faiths brought together as a milieu. Al-Andalus was a syncretic culture shaped by influences from three continents— Africa, Asia and Europe – under Muslim rule. This civilization came to be known as a golden age for setting standards across all human endeavors, a bridge between Eastern and Western learning, sciences and the fine arts, between the public and private, native and foreign, sacred and secular— a phenomenon hitherto unknown in antiquity. The decline and eventual collapse of al-Andalus is no less of a legend; it is a history of in-fighting and brutal intolerance perpetrated throughout the three centuries of the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) with ramifications to witness in our own times. The stark contrast between the Convivencia and the Inquisition makes al-Andalus a poignant story of reversals. Some people are arguing that the removal of mask mandates in hospitals is a form of eugenics. Tamara Taggart, President of Down Syndrome BC, said on “

Some people are arguing that the removal of mask mandates in hospitals is a form of eugenics. Tamara Taggart, President of Down Syndrome BC, said on “

Who doesn’t love a three-day weekend? If an extra day to relax isn’t good enough, the following week always seems to go quickly, making a Memorial Day, Labor Day, or a bank holiday in the UK, the gift that keeps on giving. Of course, most of us should consider ourselves lucky only to have to work a 5-day week. No law of the universe says a work week has to be 5 days. In fact, the concept of a 40-hour workweek is relatively new; it was only on June 25, 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which limited the workweek to 44 hours, and two years later, Congress amended that to 40 hours.

Who doesn’t love a three-day weekend? If an extra day to relax isn’t good enough, the following week always seems to go quickly, making a Memorial Day, Labor Day, or a bank holiday in the UK, the gift that keeps on giving. Of course, most of us should consider ourselves lucky only to have to work a 5-day week. No law of the universe says a work week has to be 5 days. In fact, the concept of a 40-hour workweek is relatively new; it was only on June 25, 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which limited the workweek to 44 hours, and two years later, Congress amended that to 40 hours.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.