by Rafaël Newman

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

My father’s parents were from Eastern Europe, born and raised in territories still administered by the Czar at the time of their births. They emigrated separately to Canada in the 1920s, fleeing economic ruin (in my Zaideh’s case) and Cossacks (in my Bubbi’s). Together with their birth families, and as yet unknown to each other, the two of them made it to Montreal, in those days the largest city in the Dominion and among the international goals of choice for people on the move.

Actually, to hear my Zaideh tell it, his family’s “choice” of Montreal as a destination was dictated simply by the fact that the boat for Buenos Aires had left Southampton some days before they arrived there, having made the journey from Łódź by ox-cart, train, and ferry. Furthermore, the Newmans (or Neimanns, as they were known in the Old Country) were moved to head for Montreal not only by the happenstance of timing but also by their lack of the funds necessary to pay for local accommodations until the next crossing to New York, the second best destination; and because the gangplank happened to be down on a Canadian steamer as they trundled up to the port. As for my Bubbi, who had come from a village in what is now Ukraine (on which more in a later post) and was still very young at the time she departed the Old Country with her immediate family, she had evidently been grieving for the relatives to whom she had had to bid farewell, and was thus unable to pay attention to her itinerary.

By the time I was born, my grandparents had moved away from the Plateau, the old immigrant neighborhood that had received them forty years earlier, and which had since witnessed the birth of their three children, and had established themselves in Côte-des-Neiges, a more upscale area on the farther edge of Mount Royal. Some forty years later, my parents and I lived at a still greater remove from the Plateau, on a pleasant street at the foot of Westmount, a leafy and still prosperous Anglophone enclave in what was rapidly becoming a predominantly Francophone city.

The bagel, the object of my father’s nostalgic desire in Mile End, was allegedly introduced into Montreal in 1919 by a Jewish baker from Eastern Europe dreamily identified as either Engelman or Shlafman. The bagel itself is thought to have originated in Poland, its form perhaps influenced by the stirrups King Jan Sobieski had used during his victorious charge against the Ottomans in 1683, during the Battle of Vienna, and offered as a gesture of assimilative gratitude by the Semitic confectioners of Vienna to the savior of Christendom from the presumed depredations of the Mohammedans. And indeed, the Battle of Kahlenberg, as it is known in the German-speaking world, is generally regarded as a watershed in the fortunes of the Holy Roman (AKA Hapsburg) and Ottoman Empires both, and thus a decisive turning point in the religio-cultural organization of Europe, and of its colonies.

There are, of course, as with Homer, many other sites vying for the title of the bagel’s birthplace. The Romans ate ring-shaped baked goods known as buccellata, and medieval Italians favored the ciambella and the brazatella; in modern-day Puglia province the round tarallo is a popular snack. Arabic cultures have eaten something akin to the bagel known as kak, while Uighurs are fond of the circular girde. Obwarzanki is the word used by non-Jewish Poles for their bagels, whose Yiddish name—bejgl—is thought to be cognate with the German “Bügel”, or stirrup (remember Jan Sobieski), while Ukrainians call them бублики (bubliki) or, with an affectionate diminutive, бублички (bublitchki).

The Montreal bagel, for its part, is made of yeasted dough boiled in sweetened water before baking; the ovens on St. Viateur and Fairmount are hot seven days a week, 24 hours a day (there has been recent controversy over the local environmental effects of the traditional wood-fired method). Purists eat their bagels coated in either poppy or sesame seeds, period—exotic varieties featuring blueberries and chocolate chips are ritually contemned as hybrid wannabes. And finally, the city of my birth is locked in a perpetual, if lopsided contest with New York, its American rival, whose bagels are ritually sneered at by my compatriots (and don’t even bother mentioning Toronto’s hypertrophied goyishe naches).

Despite its international pedigree, the bagel is ultimately a humble street food, its iconic hole allowing it to be threaded on a staff carried over the vendor’s shoulder. And yet for all that, the bagel appears surprisingly often in popular culture. Mordechai Gebirtig (1877-1942), a songwriter from Kraków, dedicated two ballads to the plight of the itinerant bagel peddler, while the Bronx-born Barry Sisters, née Minnie (1923-1976) and Clara (1920-2014) Bagelman, honored their birth name with the melancholic swing of “Bublitchki Bagelach” (1966). Penned in 1926 by Andrzej Włast (1885/95?-1942/43?), the Łódź-born songwriter, renowned for his sentimental szmonces, or divertissements, who died in the Warsaw Ghetto, the lyrics are a self-referential elaboration of the seller’s plaintive cry as she attempts to keep warm by singing in the frigid Odessa night:

Bublitchki,

Koyft mayne bagelach,

Haysinke bublitchki!

Nu, koyft…

Es kumt bald on di nacht,

Ich shtey zich tif fartracht,

Zet, mayne eygelach

Zaynen farshvartst.

Der frost indroysn brent,

Farfroyrn mayne hent,

Fun tsores zing ich mir

Mayn troyrik lid.

(Bagels, buy my little bagels, my hot little bagels! Step right up… Night is falling, here I stand, lost in thought, see the rings under my eyes. The frost stings, my hands are frozen, and in sorrow I sing myself a mournful tune.)

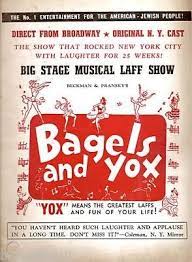

In far less plaintive fashion, the bagel’s name signals a certain half-assimilated, suburban American Jewishness in the title of Bagels and Yox, a “big stage musical laff show” that premiered in 1951. During intermissions the eponymous baked goods were provided to audiences with a shmeer of cream cheese, a preparation iconic to this day in Montreal, New York, and elsewhere in the New World, and an edible bridgehead of arriviste Jewish culture in the North American mainstream.

In far less plaintive fashion, the bagel’s name signals a certain half-assimilated, suburban American Jewishness in the title of Bagels and Yox, a “big stage musical laff show” that premiered in 1951. During intermissions the eponymous baked goods were provided to audiences with a shmeer of cream cheese, a preparation iconic to this day in Montreal, New York, and elsewhere in the New World, and an edible bridgehead of arriviste Jewish culture in the North American mainstream.

The bagel’s circular form lends itself easily to even broader symbolic implementation. Józef Piłsudski, the interwar leader of the Second Polish Republic, is reported to have compared the reborn Polish state, which he saw as a multi-ethnic historical entity rather than as a Kulturnation of blood ties, to an obwarzanek, the Polish name for the bagel: because with Poland, maintained the Marshall, as with the bagel, crisp on the outside and chewy on the inside, “the best bits are on the edges.” And in one of his justly renowned “Jewish fables,” Eliezer Shtaynbarg (1880-1932), the La Fontaine of Czernowitz, has a bagel elaborate a metaphysical system, a veritable negative theology, in refutation of two belligerently “materialist” brass buttons with whom it is sharing a pocket:

“Do you think the bagel’s more important than its essence?

Are you running from the spiritual idea? Its presence

is indeed the central core and cause of every entity,

even of crude brass,

so rude and crass.

Just out of curiosity,

cut the brass in pieces and then with care

slice the smallest sliver thin as hair,

then slowly further subdivide it like one divides the year

to months and days, hours, minutes, seconds. Isn’t it clear

that now you’re at the bagel hole, the rounded zero?

Do you grasp the thesis? Think! Now you have a mere O.

Its profundity assess and cogitate!”

(From Der loch fun bejgl un messene knepflech, “The Bagel Hole and Two Brass Buttons,” English translation from the Yiddish by Curt Leviant)

When the bagel finishes its dissertation, however, it finds that the Bolshevik buttons have disappeared: an ominous—or perhaps wishful—turn of events in interwar Eastern Europe.

*

Whatever their provenance, significance, and ingredients, bagels will always provide me with infallible access to my own species of Jewishness, which is in turn forever associated in my mind with Montreal; after all, as far as I was concerned during my formative years, Montreal was the ancestral home of the tribes of Israel. Why, for all I knew, the Holy One had commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac on the lookout spot halfway up Mount Royal, where teenagers today still park their cars (or scooters) to canoodle. And in the great cosmic game of noughts and crosses, the jovially circular bagel is the natural counterpart of the austere and forbidding crucifix—especially when the former is laden with lox, red onions, and a shmeer. How could the emaciated man of sorrows possibly hope to beat such an incentive to faith?

Now, fifty years later in Zurich, the site of my own personal diaspora, I can’t simply head across town to the old neighborhood when I am overtaken by an atavistic hunger. The nearest thing I can find to a Montreal bagel here is a Turkish bread roll known as a simit, a sesame-covered ring of chewy dough available from Zurich’s Anatolian grocers. And while I stand in line at Ege, in Feldstrasse, a döner kebab restaurant with adjoining supermarket (or vice versa), I am routinely preoccupied by the Turkish word simit, the name of my boyhood bagel’s Levantine doppelganger. Did the Ottoman Janissaries ride back to Istanbul in shame in 1683, I wonder, defeated by Jan Sobieski and buoyed up only by perverse pleasure at the memory of the succulent pastry baked, in honor of their downfall, by a people known as the Semites…?___________________________________________

An earlier version of this text appeared as part of an exhibition at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich in 2007: Ein gewisses jüdisches Etwas (A certain Jewish something) was organized by Michael Guggenheimer and Katharina Holländer under the aegis of Omanut, a society for the promotion of Jewish art in Switzerland, to celebrate that year’s European Days of Jewish Culture, and I would like to renew my thanks to the organizers, as well as to the society, for the opportunity to take part. My gratitude as well to Daniel Mendelsohn, who read that version and made useful comments, and to Joanna Rakoff, for her encouragement. Much later, in 2018, I was again asked by Michael Guggenheimer, then vice president of Omanut, to participate in an event during that year’s EDJC, at which I presented further remarks on the history of the bagel, now incorporated into the present text. I am greatly indebted to Maria Balinska, in whose marvelous The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread (Yale University Press, 2008) I learned about Eliezer Shtaynbarg, and from which I gleaned much of the cultural and historical detail included here. And now, as I post this, I am preparing to participate in yet another Omanut event, this time organized by its president, Karen Roth-Krauthammer: a reading of texts by writers in Switzerland working in languages other than the country’s official national tongues. My warmest thanks to Karen for her ongoing support and inspiration, as well as to Hella Wiedmer-Newman for appearing alongside me. Finally, I am grateful to Mariia Yevhenivna Kuleba for invaluable lexicographical assistance at the eleventh hour.