by Rafaël Newman

Leave plenty of time to stand in line at the gift shop when you visit Einsiedeln Abbey, in the Swiss canton of Schwyz. The Klosterladen, in a courtyard to the right of the 18th-century complex—which is built on the site of the 9th-century hermitage where Saint Meinrad was sustained by the Waldleute, or Forest People—sells inspirational books by religious luminaries past and present, CDs of organ music and Gregorian chants, specialty baked goods, local wines and spirits, and Einsiedler Raben, gianduja-filled pairs of chocolate ravens, as delicious as they are ominous. There are ranks of postcards, inspirational and touristic, holy pictures, incense, and all manner of candles. But the gift shop’s main attraction for pilgrims at the Abbey, long a standard stop on the Way of St. James, are its devotional trinkets: rosaries, amulets, icons, and, in particular, medallions bearing the likeness of a saint or Biblical figure, all kept in black velvet-lined display drawers at the checkout, viewable only with the assistance of the lone cashier. Pilgrims from North America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and across the Catholic world linger reverently over the offerings, oblivious to those behind them, like so many fan girls and boys at Comic-Con; and they leave, bedecked in the gawdy signs of their faith, resembling participants in a cosplay event.

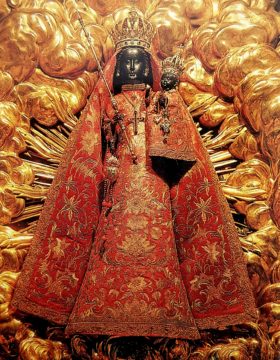

This jarring, strange-making, for believers no doubt sacrilegious impression, of an ancient, global monotheism as modern sci-fi genre, is compounded, as well as mitigated, by a glimpse of the proper object of the pilgrims’ veneration in the Benedictine Abbey’s cathedral church. Under a soaring ceiling adorned with the most gorgeously overwrought productions of counter-reformation Baroque—putti, florets, nativities, trompe-l’œil cameos, all in icing-sugar pinks, blues, and ochres—stands the glittering black marble Chapel of Our Lady, its plain stone bas-relief insets creating a two-tone reproach to the frivolity above. Within the chapel, however, inaccessible behind its wrought-iron grilles but open to view on three sides, the sternness is tempered, like the miraculous transition from black-and-white to Technicolor in The Wizard of Oz, by a further polychrome effusion: Einsiedeln’s celebrated, late Gothic Schwarze Madonna, a foot-and-a-half-tall wooden effigy of Mary, carved out of limewood, its 15th-century paint long since worn away and blackened by soot and smoke. The Black Madonna, holding the infant Jesus in her left hand and a scepter in her right, is suspended on the back wall of the chapel against a golden bas-relief combustion of cloud and rays of holy illumination. She is regularly clad and re-clad, in keeping with the ecclesiastical calendar, in an ever-changing sacred wardrobe of 27 dresses, gorgeously brocaded and complete with all the requisite accessories (as well as a matching outfit for Baby Jesus), each with its own liturgical or geographic appellation: the “Neues Florenzer”, the “Menzinger”, the “Altes Engelweih”, the “Innsbrucker”, one more enchanting than the other. Before the chapel, with the most direct view of the effigy, pews have been erected to allow worshippers to kneel and adore the Virgin. The effect on the outsider to this rite is of a children’s birthday party, whose guests are rapt in admiration of the showpiece gift, the very latest Barbie: Diversity Queen of the Universe™.

But what are these worshippers in fact seeing? The Abbey’s website is at pains to contextualize the effigy’s color as a common feature of other such “Black Madonnas” in the Catholic world. In a hasty account of recent ethnographic and feminist studies of religion, the website describes the Madonna’s blackness not as the cause of the pilgrims’ veneration, but rather as its effect. The lighting of thousands of sooty candles by generations of pilgrims in the immediate proximity of the Lady Chapel, by this interpretation, has simply left the accretion of their reverence on the effigy’s hands and face. (The implication, of course, on a subpage that also contains 18th-century references to the original “skin color” of its painted decoration, not restored following the ravages of the French Revolutionary invasion, is that this Black Madonna does not represent a “politically correct” rewriting of the ethnicity of Jesus.)

What precisely these pilgrims have been revering in this Madonna, whatever the origin of her particular blackness, is another matter. The Mother Church? The Son of God? The Holy Spirit made flesh? Male worshippers are often conspicuously outnumbered by females: do these latter experience awe at the sight of a fellow woman spared the systemic subjugation of conventional matrimony? Do they adore this patron (matron!) saint of single mothers (or at least reconstituted families), because they are themselves such parents, or because they were raised by them? Surely there are queer and trans people among the visitors to Einsiedeln: do they sense in the story of parthenogenesis and virgin birth an adumbration of contemporary technologies beyond conventional sex and gender? Many pilgrims are doubtless themselves people of color: do they ignore the cautions on the website and revere the image of an actually “Black” Mother of God? Or are all who pray to the Black Madonna—children of mothers themselves, presumably, most of them also likely raised in some version of the “classic” nuclear family—entranced by the spectacle of the ultimate Oedipal triumph: a ménage à deux from which the father has not only absented himself before the birth of the child, but in which he was never present to begin with? Some, of course, may simply be savoring the paradox of a mother-goddess idol enshrined at the heart of an alleged monotheism. And thus perhaps, despite the assurance of the Abbey’s website, that “since Black Madonnas are Catholic cult figures, we are guided by the faith and tradition of our church,” each pilgrim’s view of The Mother—of their mother—is refracted through their own particular perversity.

Such a polysemous view of the mother is by no means limited to sacred precincts. In a new work, the French memoirist Édouard Louis renders an account of a view of his mother, seen through his own eyes over time, a view shaped by the social milieu of his birth and development—and of his mother’s ongoing campaign to reclaim mastery of that very same, heteronomous gaze. Combats et métamorphoses d’une femme (“A Woman’s Battles and Transformations”, translated by Tash Aw, to appear in August 2022) is a meditation galvanized by the recent discovery of an early photograph of Louis’s mother as a happy young woman, before her marriage to his father and his own birth; it recounts the travails of her subsequent life as a wife and mother, and her eventual escape into freedom through self-fashioning.

Such a polysemous view of the mother is by no means limited to sacred precincts. In a new work, the French memoirist Édouard Louis renders an account of a view of his mother, seen through his own eyes over time, a view shaped by the social milieu of his birth and development—and of his mother’s ongoing campaign to reclaim mastery of that very same, heteronomous gaze. Combats et métamorphoses d’une femme (“A Woman’s Battles and Transformations”, translated by Tash Aw, to appear in August 2022) is a meditation galvanized by the recent discovery of an early photograph of Louis’s mother as a happy young woman, before her marriage to his father and his own birth; it recounts the travails of her subsequent life as a wife and mother, and her eventual escape into freedom through self-fashioning.

Louis, who is unflinching in his writing, both by virtue of a programmatically explicit focus on social realia and in his disarmingly honest admission of complicity with the forces of oppression, bookends the contemporary account of his viewing the photograph with a painful scene from his childhood. When he is awakened one night, in his family’s lodgings in a working-class town in northern France, by the sound of his mother playing loud music and dancing raucously with her friends, he emerges enraged from his doorless room (doors are too expensive) to command her to be quiet: “I was so accustomed to seeing her unhappy at home that the joy on her face seemed to me a scandal, a fraud, a lie, to be unmasked as quickly as possible.” In this dancing and joyful mother, Louis has glimpsed not only the young woman he will later discover in the early photograph, still apparently present under the accretions of her subsequent social roles, but also what Maggie Nelson calls the “sodomitical mother”, the woman who scandalizes her children by claiming a jouissance unauthorized by its reproductive potential. The discordance with his habitual view of her, the sufferer of her own abjection, is unbearable: it renders her uncanny, unfamiliar, unmasterable to his gaze.

It also presages his coming struggles with a scandalous libido of his own. In En finir avec Eddy Bellegueule (2014; The End of Eddy, 2017), Louis documented his coming of age as a gay man in an environment implacably hostile to deviations from traditional gender norms; in Changer: méthode (2021) he continues the story of his escape from the constraints of class and conventional sexuality and details the baleful influence on his early self of “l’Insulte”, the socially formative ritual abuse that is used to forge conformist identities and whose theoretical underpinning has been elaborated by Didier Eribon, Louis’s mentor and associate. In the most recent work, the essay on his mother’s release from bondage, Louis remarks the same mechanism at work, as his mother is subjected to verbal abuse and sumptuary prohibitions designed to keep her in her place, both feminine-domestic and working-class modest. Indeed, Louis has spoken of the alliances “naturally” formed between queer and feminist activists, in recognition of their common struggles with heteronomous fashioning and ritualized abuse, and of their common deployment of performative practices, both to endure their subjection, and to resist it. And when Louis’s mother escapes her pre-ordained role into half-freedom—a new male partner and a para-bourgeois life in the metropolis, where she is still not fully accepted by the elegant surroundings in which she is “passing”—her emancipation is marked, and enacted, by a change of costume:

Her liberation continued. She had been living her new existence for six months. When I would visit her once a month, or every other month, to spend an afternoon with her, she would always be dressed in new clothes, and smiling. They weren’t fine clothes or particularly expensive, but it didn’t matter, she was happy to have become a woman who bought herself clothes, to be doing, as she said, what all other women do: making up her face, taking care of herself, doing her hair.

It is as if the Black Madonna were to cast off the 27 dresses chosen for her by liturgical canon and confirmed by pilgrim adoration, and to don a 28th outfit, one better suited to her new, self-chosen role beyond the limits of suffering mother. In a frivolous but telling pop-cultural echo, both of the Black Madonna’s sartorial subjection and of the provincial French mother’s partial emancipation, the 2008 rom-com 27 Dresses tells the story of a woman who moves from her heteronomous role as bridesmaid to the ostensible autonomy of bride, and stages her revenge on a world that has been consigning her to an ancillary role by dressing her 27 bridesmaids in the costumes she had had to wear at their weddings.

As it happens, on my most recent trip to Einsiedeln Abbey I was accompanied by my own mother, herself contemplating a change of costume, both professional and personal, during a ten-day visit to Switzerland. We admired the Abbey ceiling and the Lady Chapel, waited in line at the Klosterladen, and enjoyed a walk along the promenade that divides the Abbey grounds proper from the adjoining woodlands, home of the Forest People. The path is part theological admonition, part botanical showcase: on one side, engraved steles rehearse the Stations of the Cross, as a bas-relief Christ is alternately met by his consolers, including his grieving mother, and tormented by his persecutors; on the other side, a model row of trees and shrubs with plaques bearing their common German and Linnaean Latin names provides a primer in the local vegetation, native and imported. The powers of ancient legend and tradition, as well as of modern technologies to master and reform nature, are simultaneously on display, echoing and vying with one another in their respective campaigns to subject, and to liberate.

The afternoon was to prove transformative.