Paraglider over the center of Brixen, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Paraglider over the center of Brixen, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dearest Reader,

Thanks to your support, today it has been exactly 20 years since I started 3QD. Not many small websites last this long, especially in the increasingly difficult media landscape and the onslaught of information begging for our attention from multiple channels: social media, WhatsApp, email, etc., etc. But you have trusted and appreciated our efforts to bring you only what is interesting and important. We couldn’t have kept going without you and we’ve had fun doing the work that we do. So on behalf of all of us, thank you!

We have recently been making some significant improvements to the site, as you may have noticed. For more on the history of 3QD and how we came to do what we do, you could read this excellent profile by Thomas Manuel, “Why the Web Needs the Little Miracle of 3 Quarks Daily” in The Wire. Keep in mind that what used to be the original “Monday” essays from 3QD’s own writers are the ONLY things which now appear on the front page of the site, usually a few every day of the week except for Saturday (when we now take a complete holiday), and starting on Monday each week. The curated links which we still post every day (except Saturday) can be seen now by clicking the “Recommended Reading” link in the main menu near the top of every page.

Now help us keep going for another 20 years, and please click here now. We’ve always kept 3QD free but the donations and subscriptions from people like you are what have kept us going (and always allowed those who can’t afford a subscription, like students, to access all of 3QD free of charge). We really do need your help more than ever to keep human-curation alive in this AI- and algorithm-dominated digital age.

Yours ever,

Abbas

by Adele A. Wilby

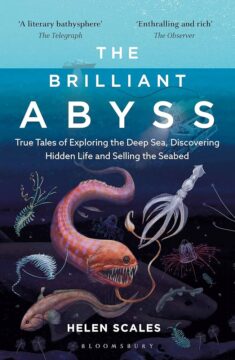

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

From the outset the breadth of Scales’ knowledge of the ocean is apparent, when, in Part One, she suggests we ‘let’ go’ of our customary understanding of time and she takes us back to the ‘backstory’ of the ocean millions, even billions, of years ago. Evocative prose render just how the pre-historic ocean floor of the Palaezoic era was swarming with trilobites of all shapes and sizes. Twenty-five thousand species of trilobites are known to have existed, yet despite their abundance not a single living trilobite can be found in today’s ocean: they went extinct. She uses this example to highlight that abundance is no guarantee of the survival of a species in the ocean.

Scales continues to narrate, how, over the course of the history of the planet, catastrophic natural events have periodically decimated ocean life. Fewer than one in ten ocean species survived the Permian extinction event that ended the Palaeozoic era 250 million years ago and marked the beginning of the Mesozoic period. It is challenging for us to imagine the ocean swarming with reptiles during the Mesozoic era, yet Scales provides numerous examples of those species. Nevertheless, over the millennia of the Mesozoic era some reptiles also went extinct while others continued to evolve. In today’s ocean, the only living reptiles are sea turtles and sea snakes. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

Imagine I place you in front of a computer screen, show you the image of two coloured shapes – e.g., a yellow triangle and a red circle – and then ask you if the sentence the triangle is yellow and the circle is red describes the image. You’ll very quickly answer that it does indeed, and then you’ll probably ask me what gives – was that a tricky question? (It wasn’t.) But what if I ask you whether the sentence the triangle is yellow OR the circle is red describes the same image? Don’t imagine it and don’t answer the question – I once ran this experiment, so go and read it! The short of it is that adults do accept the OR sentence as a description of an image of a yellow triangle and a red circle, though to a lesser extent than with the AND sentences. (A previous 3QD entry discusses some of this; here.)

What if I then tell you that young children, between the ages of 3 and 6, treat disjunction or and disjunctive sentences such as [the triangle is yellow] or [the circle is red] not as the disjunction of formal logic, which is the usual case in adults – namely, such sentences are true if one or both clauses are true (a clause is what appears within brackets) – but as if disjunction and disjunctive sentences were conjunction and and conjunctive sentences – that is, for young children disjunctive sentences are only true if both clauses are true (to wit, the triangle is yellow AND the circle is red) and not true if only one of the clauses is true.

This particular result has been obtained in a few experiments, and though it is regarded as a mistake – disjunction ought to allow for a situation when only one clause is true, otherwise why use disjunction instead of conjunction?! – it does seem to tell us something about how children acquire the logical connectives and and or (the usual story is that children’s semantic and pragmatic abilities do not develop paru passi).

I gave this sort of experimental undertaking a go recently by focusing on much younger children, the so-called “terrible twos” (around 24 month old), as the children from previous experiments tend to have an average age of 4 years, and by then children already manifest rather sophisticated linguistic abilities. And to that end we used the so-called intermodal preferential looking paradigm (the IPLP). The IPLP has been successfully used to study the acquisition of grammatical phenomena with children as young as 13-15 months and has been especially useful with children aged 18 months and above, so perfect to our purposes! Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

Part I of this is here.

#4: OWWW

Pain is a private experience that happens within an individual body; it is internal and essentially invisible. As much as we might commiserate, we cannot “share” another’s pain; we can merely witness the behavior it induces, inquire into the nature of the pain, and try to help alleviate it.

A medical diagnosis depends on a precise description. Is the pain aching, searing, shooting? Does it prick, stab, sting, or throb—or does it gnaw, tingle, cramp, burn? Is it sharp or dull? Asked to evaluate the intensity of their pain on a scale of one to ten, patients often find themselves at a loss. It hurts, they say. It’s unbearable. Pain is one of the least communicable human experiences.

Pain is also a weapon: power is asserted through violence, in other words, through causing pain. War’s objective is to shoot, burn, blast, and otherwise annihilate human flesh and to damage or destroy objects human beings regard as extensions of themselves: their homes, their possessions, photographs of loved ones, the buildings they live in, their religious and cultural institutions—and often entire cities, along with the history preserved in their architecture, in their libraries, museums, archives. War aims to not merely seize territory and take control, but to induce pain—and to make that pain visible to demoralize its victims, rob them of their voice, their individuality, their humanity.

Foucault described the process whereby the public execution—historically staged as entertainment for the masses—gradually became obsolete. In the practice of extrajudicial torture, however, the spectacle lives on. While the interrogation-induced confession is presented as torture’s justification, incriminating information obtained under duress is generally deemed unreliable or worthless. The infliction of pain serves a different purpose: torture becomes a ceremony, a form of clandestine theater where coercion and admission of guilt merge in a ritual whose power is rooted in secrecy. Read more »

by Raafat Majzoub

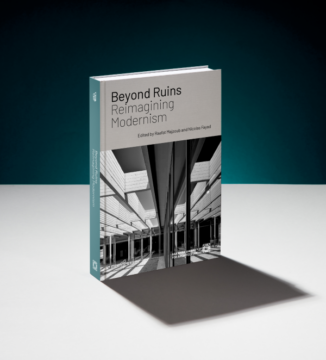

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—Raafat Majzoub invites Costica Bradatan to discuss failure in lieu of architecture’s role as a narrator of civilization and to unpack preservation as a grounding human instinct.

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—Raafat Majzoub invites Costica Bradatan to discuss failure in lieu of architecture’s role as a narrator of civilization and to unpack preservation as a grounding human instinct.

Preorder your copy here.

Raafat Majzoub: I am curious about your perspective on ruins. They seem to be closely connected to failure and humility, topics you engage with in depth in your latest book, In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility.[1] Failure in the sense of languages becoming ruins after their utility dies off, buildings becoming ruins for lack of management or maintenance, ideologies becoming ruins for the depletion of stamina.

Costica Bradatan: Ruins seem indeed closely connected to failure and humility, but perhaps in a manner even more dramatic than the one you suggest. The sight of ruins, as you point out, may evoke poor management or even a complete failure of maintenance. It is almost common sense: bringing something into existence is only one half of the process; the other half is keeping it in existence, which makes it, I imagine, a process of continuous creation.

Yet the presence of ruins signals something deeper, more serious, and more devastating: the fundamental precariousness of all things human, the eventual ruination of everything that comes from our labour, the “vanity of it all”. No matter how much care we take of something, how much time and effort we invest in its maintenance, it will eventually “fall into ruin”. Ruins are our destiny.

In this sense, ruins remind us of just how close to nothingness we always are. They are part of this world, and yet they evoke another. They are a border marker – literally, the boundary stone – that separates two realms: existence and non-existence. And in that respect, they are fascinating objects to study. They signify the nothingness in the proximity of which all things human exist, and to which they will return eventually. Read more »

by Katalin Balog

Not so long ago, people had a very different concept of the mind and human nature. Our European heritage is a vision of the body as our mortal coil which we feel and command with our soul. The soul was thought to be immortal and exempt from the laws of nature so that our actions are not determined by anything outside of the boundaries of the soul. Souls of all sorts, of angels and spirits in addition to humans, permeated the universe. The universe was an ordered cosmos with human beings at the center of it with a very special role to play in it. It was commonly held that only the soul can truly exhibit creativity and intelligence which no mere mechanism could replicate. Dreams and visions were considered important messengers. All this is quite intuitive; and its remnants are probably deeply ingrained in the everyday manner in which we still think about ourselves. Descartes – who was also one of the founders of modern science – gave voice to many of these views in his philosophy and his influence on the field remains to this day.

During the last three hundred years, and especially in the 20th century, science has ushered in monumental changes in how we think about ourselves. It has become common knowledge that the mind and the brain are tied together in a systematic way. But what proved most consequential is the tremendous progress of physics, and in particular the idea, generally endorsed by scientists and philosophers, that every physical event can be fully explained in terms of prior physical causes. Since physical events include the movements of our bodies through space, it follows that our actions have purely physical causes. Since this leaves no room for the independent causal agency of the soul, belief in an immaterial, immortal soul not determined by physical reality has steadily declined. Materialism – or, as it has recently been dubbed, physicalism – the view that everything in the universe, including minds, is fundamentally physical, is ascendent. According to physicalism, mental processes – like feeling hungry or believing that most kangaroos are left-handed – happen in virtue of complicated physical processes in the brain. The recent rise of artificial intelligence is calling into question the uniqueness of human creativity, the very idea of distinctly human activities such as storytelling, poetry, art, music. Some predict that artificial intelligence, even perhaps soon, will be able to replicate every aspect of our humanity, except, arguably though controversially, conscious experience. There is not much about the premodern conception that has survived these changes, except the view that we are conscious beings, i.e., that there is, in Thomas Nagel’s expression, something it is like to be us. There is something it is like to hear the waves lapping against the shore or seeing water shimmering in a glass. Being a human being who perceives the world, and who thinks and feels, comes with a phenomenology of which we can be directly aware. Read more »

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Pigment prints and silver halide holograms; 12 artworks.

“Holoflora names a series of artworks that tell the story of Birmingham’s vanished flora. Each work documents a location in Birmingham, as it appears today, where an individual plant species was last recorded within the present city limits. Floating within each photograph is a spectral image of the lost plant, reconstructed as a virtual botanical model. These images are holograms–a photographic technology that was invented in the West Midlands by the physicist Dennis Gabor.

Some species represented, like the fly orchid, haven’t been seen in Birmingham for over a hundred years. Others, like the orange foxtail, were recorded just a few decades ago. Many species disappeared as the environment changed–as woodlands were cleared and fens drained. A few species have always been uncommon in the region. The title of each work includes the species’ common and scientific names and the location and year of its last observation in Birmingham.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mark Harvey

When eating an elephant take one bite at a time. ––Creighton Abrams

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

I like to think that President Biden played a bit of Kasparovian chess in delaying his withdrawal from the November election until after the Republican convention in Milwaukee. I don’t know if there’s any truth to my fantasy, but in many ways the timing was perfect. The entire Trump campaign was centered around defeating an aging president who was showing alarming signs of mental decline. Despite some real accomplishments like the passage of the infrastructure bill and multiple wins for conservation of the natural world, Biden appeared to be headed for defeat. The attempted assassination of Donald Trump galvanized an already cultish following and the Democratic Party was in the doldrums—vanquished and confused.

Oh what a difference a week makes!

At this writing, no one yet knows who the Democratic nominee will be now that Biden has withdrawn from the race, and frankly a lot of us aren’t that choosy as long as he or she has a pulse and beats Donald Trump in November. It appears that Kamala Harris will be chosen and money—the singular expression of enthusiasm in American politics—is rushing in like a storm. Harris raised more than $80 million in just 24 hours. Read more »

by Richard Farr

In 2001, in order to become an American citizen, I had to “absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen.”

Abjure. Prince. Potentate. That this vocabulary from the 1790s persisted as a vehicle for solemnity was appropriate, no doubt. It also struck me as droll, in the circumstances: it was so stereotypically English. And the abjuration itself was a shame because up to then I’d always found Queen Elizabeth (or Mrs Windsor, as we liked to call her) an unfailingly pleasant and undemanding potentate. But for the sake of George II — the American potentate at the time, from whom I received a very nice letter of welcome — abjure I must.

Or perhaps in one sense I could not? For there was a detail I neglected to disclose, or couldn’t find the words to disclose, at my citizenship interview. I had lived in the United States for nearly twenty years at that point. I had acquired an American wife and American sons, and been called out by my sister on the inevitable accent shift: “You’ve started to say ‘pay-us the buddr.’”

Yet I felt as English as the day I arrived. Read more »

by Gary Borjesson

I invite you to explore with me what hospitality is, and why it’s an essential and cosmic principle of all life, but especially human life. The heart of hospitality is to provide the occasion for getting to know anyone or anything. I assume here that “getting to know” is useful and good, and hope that seeing hospitality in a fresh philosophical light will inspire and encourage more (much needed) hospitality.

Hospitality’s main features are writ large here, in our meeting. You are my host, and I the guest receiving your hospitality in the form of your precious attention. In return, I am singing for my supper. This hoped for reciprocity and mutual benefit is a feature of hospitality. I say, hoped for but not guaranteed, because getting to know something involves us in what’s unfamiliar, and to that extent unpredictable. In our case, even if you know me, you don’t know the story I’m about to tell, or how you’re going to feel about it. Depending on whether you like my song, you may kick me out of your mind before I come to the end; or you may hear me out and find (so we both hope!) that your hospitality is repaid by what I’ve offered.

Now is a good time to revisit hospitality. Its brave and welcoming spirit offers a remedy to the forces of polarization, tribalism, and xenophobia that make our time feel so inhospitable. It’s part of any treatment plan that addresses what I’ll call our individual and collective autoimmune disorders, in which parts of the same person or psyche or family or country or planet turn against each other—to their mutual detriment. Sadly, our time is not exceptional. In the face of what’s unfamiliar, our first survival instinct is to fear, flee, freeze, or fight—even when what we’re facing is an unfamiliar part of ourselves. In psychoanalytic terms, we fear, hate, rage, deny, split, and project.

True hospitality requires courage because facing our fears and opening ourselves to what’s unfamiliar is risky. For, not only is there no guarantee how meetings between strangers will go, there’s no denying it may go badly. Macbeth welcomed the king as a guest in his home, and then killed him in his sleep. Menelaus welcomed Paris as his guest, only to have Paris make off with his wife, Helen. These abuses of hospitality were catastrophic for all parties. Even in our little meeting, there’s the risk you’ll feel you’ve wasted your time, or I my song. Read more »

by John Hartley

“To err is human,” observed the poet, Alexander Pope. Yet, why do we consciously choose to err from right action against our better judgement? Anyone who has tried to follow a diet or maintain a strict exercise regime will understand what can sometimes feel like an inner battle. Yet why do we stray from virtue, choosing paths we know will lead to inevitable suffering? Force of habit? Addiction? Weakness of will?

This crisis of moral choice lies at the heart of Western philosophy, as the Ancients crafted their doctrines to explain why individuals often fail to realize their good intentions. “For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out.” Observed St Paul, “For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do–this I keep on doing.”

Akrasia in ancient thought

Homer’s Iliad paints a poignant portrait of humanity, ensnared in a cycle of necessity. This relentless loop can only be broken by wisdom and self-knowledge, encapsulated in the Delphic maxim “know thyself.” Socrates, however, argued that true knowledge of the good naturally precludes evil actions (If you really know what is right you will not do wrong!) He contends that misdeeds arise not from a willful defiance of the good but from flawed moral judgment—a tragic aberration, mistaking evil for good in the heat of the moment.

Plato linked wisdom and necessity to the duality of good and evil. He envisions self-realization and ordered integration as pathways to the good (inefficiency and unrealized potential signify malevolence). For Plato, good and evil are not external forces but internal currents: one flowing with love and altruism, the other emanating greed, envy, and malice.

The ascent to goodness, according to Plato, hinges on self-mastery and moral transformation, guiding one’s life towards the ideal form of goodness. Stoicism, of course, has experienced something of a resurgence of late, owing to Gen Z influences advocating extreme self discipline and heightened personal responsibility. Read more »

by Rachel Robison-Greene

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

For example, a recent study revealed that most people believe that artificial intelligence systems such as ChatGPT have conscious experiences just as humans do. Perhaps this is not surprising; when questioned, these systems use first personal pronouns and express themselves in language in a way that resembles the speech of humans. That said, when explicitly asked, ChatGPT denies having internal states, reporting, “No, I don’t have internal states or consciousness like humans do. I operate by processing and generating text based on patterns in the data I was trained on.”

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the loneliness epidemic by “befriending” chatbots. All too frequently, users become addicted to their new “friends,” which impacts their emotional wellbeing, sleeping habits, personal hygiene, and ability to make connections with other human beings. Users may be so taken in by the behavior of Chatbots that they cannot convince themselves that they are not speaking with another person. It makes users feel good to believe that their conversational partners empathize with them, find their company enjoyable and interesting, experience sexual attraction in response to their conversations, and perhaps even fall in love.

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the loneliness epidemic by “befriending” chatbots. All too frequently, users become addicted to their new “friends,” which impacts their emotional wellbeing, sleeping habits, personal hygiene, and ability to make connections with other human beings. Users may be so taken in by the behavior of Chatbots that they cannot convince themselves that they are not speaking with another person. It makes users feel good to believe that their conversational partners empathize with them, find their company enjoyable and interesting, experience sexual attraction in response to their conversations, and perhaps even fall in love.

Chatbots can also short-circuit our ability to follow epistemic norms and best practices. In particular, they impact our norms for establishing trust. It is tempting to believe that machines can’t get things wrong. If a person establishes what they take to be an emotional connection, they may be more likely to trust a chatbot and to believe targeted disinformation with alarming implications for the stability of democracy. Read more »

Vineyard in Neustift, South Tyrol. Apparently they put these rose bushes at the ends of the rows of grape vines because they are more susceptible to certain diseases and insects and act a bit like canaries in coal mines. Read more »

by Mike O’Brien

First, some good news: I finally understand the Monty Hall problem. Or, at least, I feel like I do, which is still a triumph of sorts, given that this riddle’s empirically incontestable answer tends to evoke visceral, intuitive rejections, even among people who understand and accept every step of the explanation. I first encountered this wicked little brain teaser years ago during my undergrad philosophy studies, and only last week did it click into comprehension, thanks to a fine article by Allison Parshall in the August 2024 issue of Scientific American. The explanation that made sense to me is roughly as follows: When you choose one of three doors, there is a 1/3 chance that the prize lies behind it, and a 2/3 chance that the prize lies behind one of the two doors not chosen. When the host reveals that one of the two unchosen doors has no prize behind it, the odds are unaltered in the sense that there is still a 1/3 chance that the prize lies behind the door initially chosen, and still a 2/3 chance that it lies behind behind one of the doors not chosen. The host’s action just collapses that 2/3 chance into the single remaining unchosen door. So, while the player’s choices are split “50/50” between two remaining options (stay with the already chosen door, or switch to the remaining unchosen door), the odds remain 1/3 (behind the chosen door) versus 2/3 (behind the two unchosen doors, of which only one can now be chosen).

I had come close to understanding this last year when reading another discussion of the problem, which expanded the scenario to 100 doors, with Monty opening all but one of the 99 doors not chosen by the player in the first step of the game. In both the 3-door version and the 100-door version of the game, Monty opens all but one of the doors not chosen, collapsing the distribution of the odds into one remaining choice (2/3 or 99/100, respectively). It was intuitively obvious that if Monty opened all but one of the 99 unchosen doors, then that remaining door was more likely to hide a prize than the one randomly chosen by the player at the start of the game. But the idea that the odds remain the same, while the freedom to choose the wrong door shrinks, didn’t click yet. Now it clicks. I thank Parshall for removing one small but stubborn source of frustration from my life.

And now, a little chronicle about my other problems and solutions. Read more »

by Eric Schenck

I’ve been surfing for about three years.

I’ve been surfing for about three years.

Not enough to be a guide of any sort, but certainly enough to realize what a miracle the sport really is.

What follows are nine life lessons surfing has taught me. The more you do anything, the more you realize it can teach you about everything.

I built a surfboard with my dad when I was 18. In my American high school, you needed a “senior project” in order to graduate.

I’d always wanted to surf, and my dad is a carpenter who can make just about anything. It was a match made in heaven.

When we finally finished putting the orange paint on and it dried out, I officially had a surfboard. I was going to start right away. A new “surfing bro” identity was just around the corner, and the world seemed full of possibility.

It took 10 more years before I went surfing for the first time. I still haven’t even taken my senior project out for a spin.

But I’m here now, and I’m surfing a lot, and I’m about twice as good as I was last year.

Things don’t need to be perfect before you can invite a little more joy into your life.

I started a decade later than I planned – but I started.

And that’s what matters.

I wish surfing was easy. Or at least one of those things that you can learn from watching a bunch of videos.

But you can’t.

Before my first time out, I spent a few hours on YouTube. Learning how to paddle, studying the drop in, watching videos of the surfing greats.

It didn’t help a bit.

That first day, the ocean forced me into the gap between planning and practice. Read more »

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Barry Goldman

Imagine a hunter, a tree, and a squirrel. The hunter is on the ground, the squirrel is clinging to the tree, and the tree is between two of them. As the hunter moves, the squirrel moves, always keeping the tree between them. The hunter goes around the tree. Does he go around the squirrel?

Yes. The squirrel is in the tree, and the hunter went around the tree. Therefore, the hunter went around the squirrel.

No. In order to “go around” the squirrel, the hunter must at some point be in front of the squirrel, and at other points he must be to the squirrel’s right, behind the squirrel, and to the squirrel’s left. That’s what it means to “go around” something. The hunter in the hypothetical was always directly facing the squirrel. He was never to the squirrel’s left or right and he was never behind the squirrel. Therefore, the hunter did not go around the squirrel.

So it depends on what “go around” means. If you adopt one definition, the hunter went around the squirrel. If you adopt the other, he didn’t. So what? Who cares?

That’s fair. But it isn’t so much the hunter and the squirrel I’m concerned about. I’m interested in legal disputes. And the judicial interpretation of contracts and statutes presents just this question: When we have competing definitions, how should we go about determining which one to adopt?

Let’s try another example. Is a taco a sandwich? That sounds like the same kind of silly waste of time as the hunter and the squirrel problem, and it is. Until it becomes the subject of a lawsuit. Read more »

by Eleni Petrakou

It’s late 2022. Scientists announce the creation of a spacetime wormhole. A flurry of articles and press releases of the highest caliber spread the news. Involved researchers call the achievement as exciting as the Higgs boson discovery. Pulitzer-winning journalists report on the “unprecedented experiment”. US government advisory panels hear it is a poster child for doing “foundational physics using quantum information systems”. Media the world over are on fire.

All the while, the scientific community is watching, dumbfounded.

Because, of course, nobody had created any spacetime wormhole.

*

Now that all the rage is well gone, it’s probably worthwhile to revisit that episode with the proverbial hindsight.

Specifically, the events of November ’22 kick off with an article in Nature detailing the creation of a “holographic wormhole” in Google’s quantum labs. On the same day, the prescheduled publicity by respected science outlets is crazy –the announcements by participating elite universities don’t hurt either– and sure enough the story quickly makes headlines all across muggle media.

To keep things in context: in case you are wondering if wormholes are something whose existence would shake a large part of what physics we know and, even if they exist, we might be technological centuries away from their handling, you are right. This is why all experts not connected to the study reacted with unbridled skepticism. Read more »