by Ed Simon

Demonstrating the utility of a critical practice that’s sometimes obscured more than its venerable history would warrant, my 3 Quarks Daily column will be partially devoted to the practice of traditional close readings of poems, passages, dialogue, and even art. If you’re interested in seeing close readings on particular works of literature or pop culture, please email me at [email protected]

The shortest lyric in Natalie Diaz’s 2013 collection When My Brother Was an Aztec has two less words than its title does. At only five words, the poem “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Towards Jesus” is, because of its length, an incongruous entry in the collection, which for the most part combines more conventional quasi-formal and free verse that ranges from a few dozen lines to a few pages. Brevity is, of course, not necessarily a marker of radicalism; after all, the lyric as a form was originally defined not just by a strong individual voice, but also by representing a brief observation or emotion rather than a narrative with epic scope. The traditional Japanese genres of haiku, sijo, and tanka are marked by an economy of precision, but in the West even that most venerable form of the sonnet makes its argument and takes its logical turn in a short fourteen lines. Then there are the poets with a reputation for parsimony, masters of concision such as Emily Dickinson or Edna St. Vincent Millay. Still, a short Millay work such as “First Fig” (“My candle burns at both ends.”) with its four lines and twenty-five words might as well be the Iliad; a Dickinson lyric such as “Poem 260” (“I’m Nobody! Who are you?”) at eight lines and 42 words is a veritable Odyssey when compared to Diaz. When a poem counts in at under a dozen words, or even under half-a-dozen, there is a suspicion that the poet is courting the gimmick more than anything, the purview of the limerick and bawdy lyric, of Strickland Gillian’s “Lines on the Antiquity of Microbes,” which has been claimed as the briefest poem in the language, reading in its entirety “Adam/Had ‘em.”

There is nothing of the gimmick in “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Towards Jesus,” however, even if it has three more words than does Gillian’s lyric, though Diaz’s poem also isn’t without its playfulness. The five-word poem, in its entirety, reads “weeping/blooms/of/white/smoke” though the enjambment marks reproduced in this sentence give precious little credit to the manner in which Diaz uses space and arrangement to convey meaning beyond the mere semantic. To begin with, the lyric is read from top to bottom, but vertically speaking none of the words are arranged in an exact straight line, so that “blooms” is slightly below “weeping,” “of” is slightly above “white,” and so on. Horizontally the arrangement of the words in relation to one another is even more marked in difference, a wide gap between “weeping” and “blooms,” an even wider one between “of” and “white,” nearly three times the distance in what’s an unconventional caesura. The first four words of Diaz’s poem are, nonetheless, roughly paired off into respective partners, so that the final word “smoke” is very obviously alone. The overall effect, then, is that “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Towards Jesus” appears as if the very thing that it’s about; the shape of the poem is as if a puff of smoke rising upward and moving off towards the west from the word “smoke” itself. By yoking meaning not just to the semantic, but to the shape of the poem itself, Diaz has written an example of concrete poetry in the tradition of George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” or Lewis Carrol’s “The Mouse’s Tale,” not to mention the centuries-long tradition of Islamic calligraphy.

“Smoke” is the operative theme in Diaz’s poem, not just because the poem itself resembles a misty vapor of lines, but because the title itself mentions that related concept of “clouds.” In this way, “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping toward Jesus” is able to cheat a little, for it would be a mistake to only consider the poem in terms of the five words that make up the text itself and not the seven additional words that constitute the paratext of its title. Not that the title of any poem ever need be incidental, but in a longer work the relationship between a title and the lyric can be more relative than in verse as brief as Diaz’s, where that ratio between the two becomes more startling. And so, between the title and the text we have four arresting concrete nouns in the smoke, the clouds, the buffalo, and Jesus (while “blooms,” depending on if it’s read as a verb or not, could also possibly be added). An elemental, if not archetypal, assortment of images. The first thing that could be initially assumed in a five-word poem written a century after the Modernist literary revolution is that Diaz’s is a homage to poets like Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, her poem possibly being a similar experiment in succinctness. Like Williams and Pound, Diaz arrests the reader into a singular moment (in this case smoke rising in the air), so that “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Toward Jesus” recalls the former’s “The Red Wheelbarrow,” or the latter’s “In a Station of the Metro” with Pound’s evocation of “The apparition of these faces in the crowd:/Petals on a wet, black bough.”

Similar evocations possibly, but a superficial comparison, for the Imagists followed Williams’ dictate that in poetry there were “No ideas but in things,” but Diaz’s lyric is very much concerned with ideas, perhaps even symbols. Here then Diaz diverges from the Imagists, for if that crystalline simplicity in Pound and Williams was intended to convey a perfect image, the contemporary poet is after something different, rather. That is to say that in Pound’s poem, the apparition, the faces, the crowd, and the very “Petals on a wet, black bough” don’t mean anything; William’s eponymous red wheelbarrow glazed with rain and the chickens clucking about it aren’t representative or symbolic. What they happen to be are a red wheelbarrow and some chickens. By contrast, in “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Toward Jesus,” those aforementioned nouns, the cloud and the smoke, the buffalo and Christ, are loaded with meaning beyond imagery, even if it would also be a mistake to interpret them as ciphers.

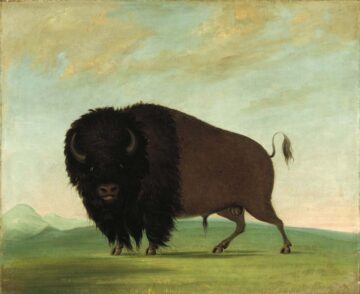

Throughout When My Brother was an Aztec, Diaz – an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Reservation and a professor at Arizona State University – is concerned with indigeneity and the syncretism of faiths both Indian and Christian, Mojave and Catholic. Read in this context, the tension between Indian religion and Christianity, as well as their fruitful synthesis, is clear in the short lyric, but even when read alone and stripped of those relationships to the pieces in the rest of this collection and Diaz’s theme is clear. This is obvious, to begin with, in the title’s mention of “Jesus.” The Son of God is placed in relationship to those “Buffalo” in the title, the totemistic (if not stereotypical) animal associated with the American Indians, especially when as white as clouds. Yet these aren’t buffalo, these are “clouds,” as Diaz writes in the title, the metaphorical association between the shapes of those clouds and the animals which they look like a chimera, not a reality. That they’re “limping” toward Jesus is a fascinating verb, for do we see this as a genuflection, a posture of defeat, or perhaps a desire for supplication, these illusory beasts making their pretend pilgrimage toward the messiah?

For that matter, how are we to read these “weeping blooms?” Is the white smoke itself a bloom which is weeping, or, rather, is the billowing of the white smoke merely compared to blooms? There is, to be sure, great power in the word “blooms” itself, connotating not just the obvious floral implications, but the blooms of blood that result from the piercing of flesh, a connection made all the more potent (and portent) with the adjective that modifies that word. That adjective in question, “weeping,” is itself fraught with significance, with its clear associations of mourning and melancholy. Is Diaz perhaps enacting in a five-word poem the eclipse of the old ways in favor of the colonizer’s religion? Yet Christianity and Indian beliefs are not necessarily so easily unextracted either, for the white smoke of the poem evokes both that which signals the election of a new pontiff in the Roman Catholic Church, but also the fires of Indian powwows, a synthesis of two disparate traditions that, as the entirety of When My Brother was an Aztec makes clear, have been in a fraught relationship for more than five centuries. Nor would it be accurate to see these limping buffalo, these dark clouds with their whisps shaped as spindly legs and their cumulous hump, as mere epiphenomenon headed towards Christ, who is not necessarily any more real than they are, for the poem is ambiguous on that score. Rather what we have is a smoldering fog of meaning, where words that are the very medium of sense waft upwards towards a nonexistent heaven like smoke from a quenched fire whose leftover ashes are soon to be as dry and cold as dead faith.