by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Akim Reinhardt

Dreams are about questions.

Dreams are about questions.

Every dream sprouts up as an innocent question in the early morning haze. Maturing in bright sunlight, it opens up, like the petals on a flower, with vibrant new questions unfolding from the original. Then, after achieving its fulsome bloom, the dream begins to sag. No longer birthing new questions, its fading aroma and shriveling grandeur are pitied, mocked, and satirized before being ignored, a loyal few finally plucking its withered remnants and vainly trying to save the dream by pressing it between the pages of a book, eternally rendering it a dry, flat scrap of its former self.

[insert a dream here]

Generations of Americans dreamed dreams about liberty and greatness and free land and streets paved with gold, one flower after another emerging, blooming, and wilting, before finally being pressed into the scrapbook of history.

[insert the blood of settler colonialism here]

When the Great Depression and World War II were finally put to rest, the American dream bourgeoned in contrast to the Soviet nightmare. We must pursue this dream of new appliances in suburban homes, of passive participation in mainline Protestantism, of Barbie doll beach blanket bingo, of vanilla white velvet cake, lest the encroaching darkness of poverty, atheism, and red gulags overrun us. Onward Christian soldier, marching ever forward to material salvation.

[insert body snatchers here]

But when the procession moved only in tightly proscribed circles, a new generation planted a seed that questioned the dream itself. Where is America and its elusive dream?

[insert a Spirograph here] Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

Stanley Tucci begins his hit TV show Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy, by reminding us that, yes, he is Stanley Tucci. But perhaps more importantly, that he is “Italian on both sides.”

Yeah, yeah, I thought I was Italian too.

Life was so much easier before DNA testing. I mean, in the good old days you could just make up any old story about your family heritage –and who was anyone to contradict you? Seriously, if you told people you were Italian, then you were Italian. Finito. And I actually do have Italian blood. On my grandmother’s side. My grandma’s grandparents on both sides came from Calabria, on the Italian peninsula near the toe of the boot. They could practically see Sicily.

That is where both sides of Tucci’s heritage comes from too. I never realized until recently how many Calabrese found their way to the United States. A huge percentage of all Italian-Americans are Calabrese.

Like Tucci, I even knew their names: Tripodi (classic Calabrese name) for one great-grandparent and Pelicano for the other. Sounds pretty Italian to me.

Never mind that every time I proudly told an Italian from Rome or Milan about my Calabrese heritage they seemed to be stifling the impulse to laugh.

And never mind that I also must have Irish blood in equal portions.

Or so I thought. Read more »

by R. Passov

When I was twelve, I ran away to Disneyland; not by myself. I went with an older kid, one or two grades above me. Ed, the older kid, was ‘bad to the bone’ – so much so, he deserves his own story.

If it was still 1971, I’d say any twelve-year-old should do the same – hitchhike from the San Fernando Valley to the bus station in downtown L.A., then take a Greyhound to Anaheim. The only caveats being: don’t go with Ed and don’t torture vending machines at the bus station until they give up their quarters.

We did that. I can’t say I understood Ed’s technique. All I know is he kicked and rocked a machine until it jack-potted quarters. Two park passes barely dented the weight in our pockets.

As I remember it, a low metal picket fence boarded the grounds just past the ticket gate, giving the effect of an old railway station, letting us onto Main Street.

We weren’t in a rush. Our ticket books were letter and color coded. We had just two a piece of the best tickets – e tickets -, and an unshared understanding that our time would be spent wandering and watching.

Moonrise from my window last week.

by Rafaël Newman

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

When I asked her about this preference, my colleague explained that what she admired in such novellas was the fact that they were—and here she paused briefly to seek the appropriate English term: for she was a native francophone, and read her Japanese literature, for the most part, in French translation—“pudique.”

Now it was my turn to consult a mental lexicon. Pudique? I was reminded of the anatomical term “pudendum,” meaning the human genitals, derived from the Latin gerundive and meaning “that about which one ought to feel ashamed”. I remembered a TV news clip, viewed during a sojourn studying in Paris years ago, in which a certain politician, accused of corruption (I no longer recall whether fiscal or sexual), was seen escaping in his limousine and admonishing the reporters hounding him for a statement: red-faced with indignation, he called for the paparazzi to exhibit “un peu de pudeur”—for shame, his expression suggested, and as an Anglo-American politician in the same situation might have said. Could this really be what my colleague valued in her bedside reading: a sense of shame, of the shameful, of being ashamed, especially as regards intimate affairs? Read more »

The First Arena is that of inanimate matter, which began when the universe did, fourteen billion years ago. About four billion years ago life emerged, the Second Arena. Of course we’re talking about our local region of the universe. For all we know life may have emerged in other regions as well, perhaps even earlier, perhaps more recently. We don’t know. The Third Arena is that of human culture. We have changed the face of the earth, have touched the moon and the planets, and are reaching for the stars. That happened between two and three million years ago, the exact number hardly matters. But most of the cultural activity is little more than 10,000 years old.

The question I am asking: Is there something beyond culture, something just beginning to emerge? If so, what might it be?

Let us review.

Complexity and Abundance in an Evolving Universe

My basic thinking about the nature of the universe, about ontology and cosmology, is grounded in two ideas: 1) complexity, which I take from Ilya Prigogine, though he is by no means its only exponent, and 2) abundance, from the philosopher, Paul Feyerabend. Complexity of this kind is more than complication. It is, paradoxically, the capacity for simple systems to undergo self-organization and thereby to become more complex, and still more ever complex. And complexity accounts for the universe’s abundance.

Abundance? Here is a remark that Feyerabend made to John Horgan, the science journalist:

… he told me about a book he was working on, The Conquest of Abundance, about the human passion for reductionism. It would address the fact that “all human enterprises” seek to reduce the natural diversity, or “abundance,” inherent in reality.

“First of all the perceptual system cuts down this abundance or you couldn’t survive.” Religion, science, politics and philosophy represent our attempts to compress reality still further. Of course, these attempts to conquer abundance simply create new complexities.

The universe is complex, it is abundant, it is overflowing. It is, above all, the capacity of one arena to give rise to another: inorganic matter gives to life, life to mind and eventually to culture. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India.

Of these the most colorful person was Wendy who used to entertain us with her charming stories drawing upon the erotic aspects of ancient Hindu texts. Myron, when he was the chair of the Committee always began the meeting with his collection of jokes. Myron was downright serious, though, in his work where he was insistent in bringing to the attention of Indian policy makers the crucial importance of universal child education and reform of the prevailing, widely connived, practice of using child labor. Ralph used to share with me his stories of his experience of ethnographic work in Bengal villages (he was fluent in Bengali and during his field visits he’d often be chatted up by curious villagers who’d tell him that as he was from America interested in their lives, he must be a CIA agent, and were utterly disappointed when they heard his emphatic denial). Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

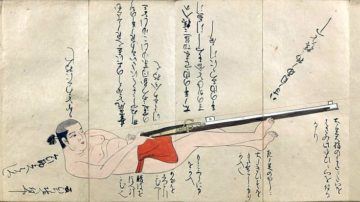

“Giving up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879”, by Noel Perrin

In 1543, a small Chinese pirate sloop with two Portuguese arquebusiers on it sailed into Tanegashima island in Japan. The local feudal lord, Tokitaka, was so impressed when he saw one of the arquebusiers shoot a duck that he promptly ordered two of the guns for a price that was to go down 500-fold over the next seventy years. The same day he ordered his swordsmith to repurpose his skills for manufacturing the new weapon.

That dramatic reduction in price shows the impact the gun had on Japan. In the next hundred years, Japanese gun manufacturing achieved a level of prominence and expertise that in many ways exceeded anything in the West; for instance, the Japanese devised the simple and yet unique expedient of protecting their gunpowder in a water-resistant pouch to prevent a matchlock fizzle, allowing them to take guns into battle comes rain or shine. Japanese metallurgy was also second to none, with cheap and yet effective Japanese copper being the envy of the West. The advantages of the gun became very apparent very quickly; in 1575 at the Battle of Nagashino, for instance, Oda Nobunaga handily defeated Takeda Katsuyori’s cavalry by mowing them down like a scythe with a sophisticated pattern of gunfire. Other engagements followed, including a war with Korea, where the practical utility of the gun was left in no doubt. It looked like, from almost any angle, Japan was set to lead the world in advanced gun warfare for the foreseeable future.

And yet after a hundred years, the reduction of gun warfare was equally dramatic, so much so that the small trickle of Western observers who managed to make it to the island nation after Japan had banned Christians thought that the country existed in a state of primitive ‘Arcadian simplicity’, completely innocent of modern weaponry. Little did they know the history which Dartmouth professor Noel Perrin recounts in this lively volume. Japan remains perhaps the only example of an advanced, intelligent nation that sampled guns and then willingly gave them up for hundreds of years. Perrin explains the why and the how here and speculates on why that might hold some lessons for our own obsession with new weapons and technology. Read more »

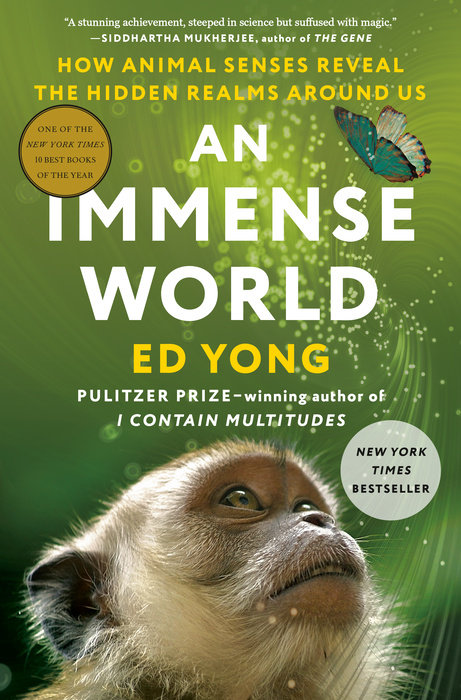

by Paul Braterman

This book is an enormous achievement. A thrilling read, taking us into the Umwelt, or perceptual world, of numerous mammal, fish, reptile and insect species. A major work of scholarship, with over a thousand references to a 45-page bibliography, as well as accounts of interviews with numerous researchers and visits to their laboratories. An exploration of many ways of sensing the world, some of which we share, while others are beyond our imagining. The evolving interplay of perception and action, communication and deception, environment and response. And an enhanced insight into what it is like to be a bat, a bird, a blue whale, a beetle, or a human.

From the wealth of detail in the book, a consistent grand narrative emerges. Some physical process interacts with living matter. This is the raw material for sensation. Sensory abilities then shape a creature’s Umwelt, being developed according to the demands of its environment. But every perceiver is itself an object of perception to others, and we have colour displays and camouflage, smells as signals and identifiers, sound as communication to others and, by echolocation, back to the creature who generates it, and the same is true of other senses that we do not share, such as the detection of tiny electrical fields. Senses combine and even, we suspect, merge, and what we ourselves perceive is but part of an immense pattern. But the heedlessness with which we amplify our own signals disrupts this pattern, contributing to our destruction of nature, and we ourselves are the poorer for it.

Let me offer a few samples from the book’s wealth of detail. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice. Some estimate membership in these communities at about 100,000 participants. Stoicism has also played a seminal role in the development of cognitive/behavioral therapy in psychology.

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice. Some estimate membership in these communities at about 100,000 participants. Stoicism has also played a seminal role in the development of cognitive/behavioral therapy in psychology.

The puzzle is why Stoicism is now having its moment—because it is genuinely weird.

To be sure, Stoic ethics gives some good advice. One central tenet is that we place far too much value on external things such as wealth, popularity, or prestige at the expense of moral virtue. In an age of celebrity worship, groveling for likes on social media, and a mad dash for cash, none of which does much to promote happiness, we could surely use more focus on what really matters in life. But this sort of advice isn’t unique to Stoicism. It is hard to imagine any mainstream ethical theory not condemning our fascination with bling, careerism, and greed. Nevertheless, the Stoic reasoning on these ethical matters is distinctive and important because it deeply shapes the practical advice that has made it so popular. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Be Unvaan. June 11, 2022, Cambridge, MA.

Sughra Raza. Be Unvaan. June 11, 2022, Cambridge, MA.

Digital photograph.

by Tim Sommers

“If guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.” I can’t find the origin of this unfortunate slogan, but it’s been around – and oft repeated – at least since the 1970s. “To stop a bad guy with a gun, it takes a good guy with a gun.” That’s Wayne Lapierre, CEO of the National Rifle Association, the day after the Parkland Shooting. The trouble with slogans and bad arguments like these is that it takes much less time to make them than it does to break them. The point of outlawing guns is to make it the case that outlaws and bad guys won’t have as many guns. But Sam Harris, prominent “rationalist”, denies that “restrictions would make it difficult for bad people to acquire guns illegally.” (Compare, restrictions on bank robbery or speeding don’t make it any more difficult for people to rob banks or speed.) Sometimes, you get a more neutral argument along the same lines. “Maybe, having a lot of guns around will lead to more violence. On the other hand, maybe, having more guns around will prevent more violence than it causes. We can’t know.”

But this is not an unknown. It’s known. More guns cause more homicides. More guns cause more suicides. It’s a simple equation. More guns = more death. There are hundreds of studies (done in just about every which way), asking whether or not increasing the availability of firearms contributes to more suicides and more homicides. It does. At this point, it’s like asking whether evolution is real, whether smoking causes cancer, or whether the increase in the level of certain gases in the atmosphere is causing global temperatures to trend upward. The answers are yes, yes, yes, and yes. These are all things we do, in fact, know.

This is important. Guns are now the leading cause of death among teenagers. And children. How can people not know that more guns lead to more deaths? Read more »

by Brooks Riley

Editor’s Note: Thomas O’Dwyer wrote almost fifty essays for 3QD which you can see here.

by Michal Yudelman-O’Dwyer

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

Thomas was so many things, but first of all a writer. He never stopped seeking facts and information up to his last night in hospital. He had a quick Irish temper and no patience for slow understanding or explaining things twice, which sometimes made things difficult, especially if you were always asking him how to do this or that on the computer, or to edit something you wrote, as I did.

He was also generous and caring and had a weakness for street cats, which he fed every day in our building’s back yard until the last trip to the hospital. All our house cats over the generations were street cats who’d wandered in, or which he’d found as kittens.

As a fearless war correspondent, he had hair raising tales, sometimes sounding, how shall I put it, somewhat enhanced. But there was nothing enhanced about his reporting. His pursuit of the truth was relentless and everything he wrote depended on the background of his vast knowledge and understanding.

His daughter Fiona said he’d told her as a child, when he was Reuters’ bureau chief in Nicosia, that as a journalist it was his responsibility to know the history of “every country in the world.” Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

It’s my last day in Paris, and a liminal one. I have to leave for the airport by 14:00 to retrieve my suitcases from my friend.

[…]

I intended to write several sentences before writing the climax of this short piece—that I wish France would say goodbye to me, that someone French would notice my absence—when a young man walked up to where I am sitting on the lawn. He wore brown sandals and a soccer uniform in bright orange and blue. His hair fell to his shoulders and he said:

« T’écrit ? »

“Sorry?” I responded.

“You are writing?”

“Yes.”

I glanced back down and finished my sentence, “…from my friend.”

He laughed softly.

“Sorry.”

He left. He walked down the lawn, and then across another.

1

I suppose he was Paris coming to say goodbye. I reacted to him as I did to the city. I engaged lightly but held back; I didn’t know how to respond to his existence; I buried my head in my journal; I kept writing to end the conversation; I pretended that I was as important as any other expatriate writer in Paris; I wanted to appear lofty and crafty; I wanted to walk away with the city’s last muse, sitting in the dregs of their coffee cup.

When I wanted to be seen by Paris, I felt ignored. On my very last day I am noticed. He has altered my premature past. Read more »

by Chris Horner

No man is a hypocrite in his pleasures —Dr Johnson

Without music life would be a mistake —Nietzsche

Music started for me with whatever was blaring out of the radio, and later those 45 rpm ‘single’ records that were the main vehicles of listening pleasure for teenagers in the late twentieth century. I heard a lot of that rather than listened to it. Listening really started with the ‘long player’ or album: 40 minutes or so over two sides of a black disc with a cover that, if you were lucky, didn’t look too bad when you gazed at it.

The first album I owned was a birthday present: Abbey Road, the final Beatles recording. Having nothing else to play, this got a lot of spins, first through the big speakers of my parents ‘Rigonda Stereo Radiogram’, then with the earphones plugged into the back with the lights off. In a private darkness the music and the lyrics were undisturbed by the banality of our front room, and the thing became something I knew by heart, images and melodies imprinted like a recurring, waking dream. Only the pleasure principle mattered: I has no idea whether I was supposed to like this stuff, I just did. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In the 1990’s Andrei Shleifer was only one among many in the proselytizing army of reformers who went out to the transition economies, mainly in Central and Eastern Europe but also in developing countries, to make them ready for capitalism. They were in a hurry to implement reforms of liberalization and privatization according to some general, often one-size-fits-all, formula. The purse strings of emergency financial help by international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank and US agencies like USAID were also controlled by stern macro-economic ideologues of ‘structural adjustment’. The reformers were in possession of the canonical gospels which it was their sacred duty to spread among the heathens as quickly as possible, given the golden opportunity after the fall of the godless communists and socialists.

In the 1990’s Andrei Shleifer was only one among many in the proselytizing army of reformers who went out to the transition economies, mainly in Central and Eastern Europe but also in developing countries, to make them ready for capitalism. They were in a hurry to implement reforms of liberalization and privatization according to some general, often one-size-fits-all, formula. The purse strings of emergency financial help by international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank and US agencies like USAID were also controlled by stern macro-economic ideologues of ‘structural adjustment’. The reformers were in possession of the canonical gospels which it was their sacred duty to spread among the heathens as quickly as possible, given the golden opportunity after the fall of the godless communists and socialists.

I went to some of the international conferences on the Economics of Transition in this period, held usually in cities like Budapest or Prague or Riga. Soon I gave up going to such conferences as I felt I did not know enough of those countries to really say anything that’d make sense to the local audience. But I did go to one organized in Kolkata by the eminent political economist Mancur Olson. (Mancur grew up in a Norwegian-American family in North Dakota. When he came to know that the name Mancur, a traditional name in such Scandinavian families, was a variation of the Arabic name Mansoor, he speculated: “In fanciful moments, I imagine a Viking raid on the Levant.”) I had admired his past work on collective action and I thought he deserved a Nobel Prize for that work, which he did not get. When he asked me to contribute to a collection of essays on institutional economics he coedited, I gladly did. Read more »