by Ada Bronowski

![]() More than an age of anxiety or anger, of indignation or self-righteousness, we live in an age of the constant high. We need not consume drugs or get inebriated to be met on a daily basis with sights and behaviours to which the only reasonable reaction is an alternation between ‘wow!’ and ‘oh my god…!’ From the still-not-yet-former British prime minister saluting the oldest of the modern parliaments with a deep-felt ‘Hasta la vista baby!’, to newspaper frontpages, to twitter feeds, the most pervasive mode of communication in contemporary society is the exclamation. Social media experts and communication analysts of every stripe routinely provide us with statistics demonstrating the normalisation of the exclamation point as a sine qua non of everyday communication. It is the lack of one which legitimately arouses concern. The use of a full stop at the end of a sentence tends rather to indicate that something is not quite right. Whether you write a text saying: ‘I’m waiting.’, or whether you write: ‘I’m waiting!’, the recipient knows either to be worried they have annoyed you in the former case, or that all is fine in the latter case, though without then assuming any particular degree of excitement. Whether someone writes in an email or text: ‘That’s perfect.’ or ‘That’s perfect!’, you sense in the former case, that something is in fact not quite perfect, whereas in the latter case, you do not consider anything’s being either perfect or not. The exclamation point, rather than emphasise excitement, functions as a neutraliser, shifting the focus of a sentence away from its actual content. Read more »

More than an age of anxiety or anger, of indignation or self-righteousness, we live in an age of the constant high. We need not consume drugs or get inebriated to be met on a daily basis with sights and behaviours to which the only reasonable reaction is an alternation between ‘wow!’ and ‘oh my god…!’ From the still-not-yet-former British prime minister saluting the oldest of the modern parliaments with a deep-felt ‘Hasta la vista baby!’, to newspaper frontpages, to twitter feeds, the most pervasive mode of communication in contemporary society is the exclamation. Social media experts and communication analysts of every stripe routinely provide us with statistics demonstrating the normalisation of the exclamation point as a sine qua non of everyday communication. It is the lack of one which legitimately arouses concern. The use of a full stop at the end of a sentence tends rather to indicate that something is not quite right. Whether you write a text saying: ‘I’m waiting.’, or whether you write: ‘I’m waiting!’, the recipient knows either to be worried they have annoyed you in the former case, or that all is fine in the latter case, though without then assuming any particular degree of excitement. Whether someone writes in an email or text: ‘That’s perfect.’ or ‘That’s perfect!’, you sense in the former case, that something is in fact not quite perfect, whereas in the latter case, you do not consider anything’s being either perfect or not. The exclamation point, rather than emphasise excitement, functions as a neutraliser, shifting the focus of a sentence away from its actual content. Read more »

“

“ In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

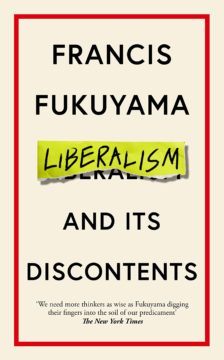

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor. Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch  I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

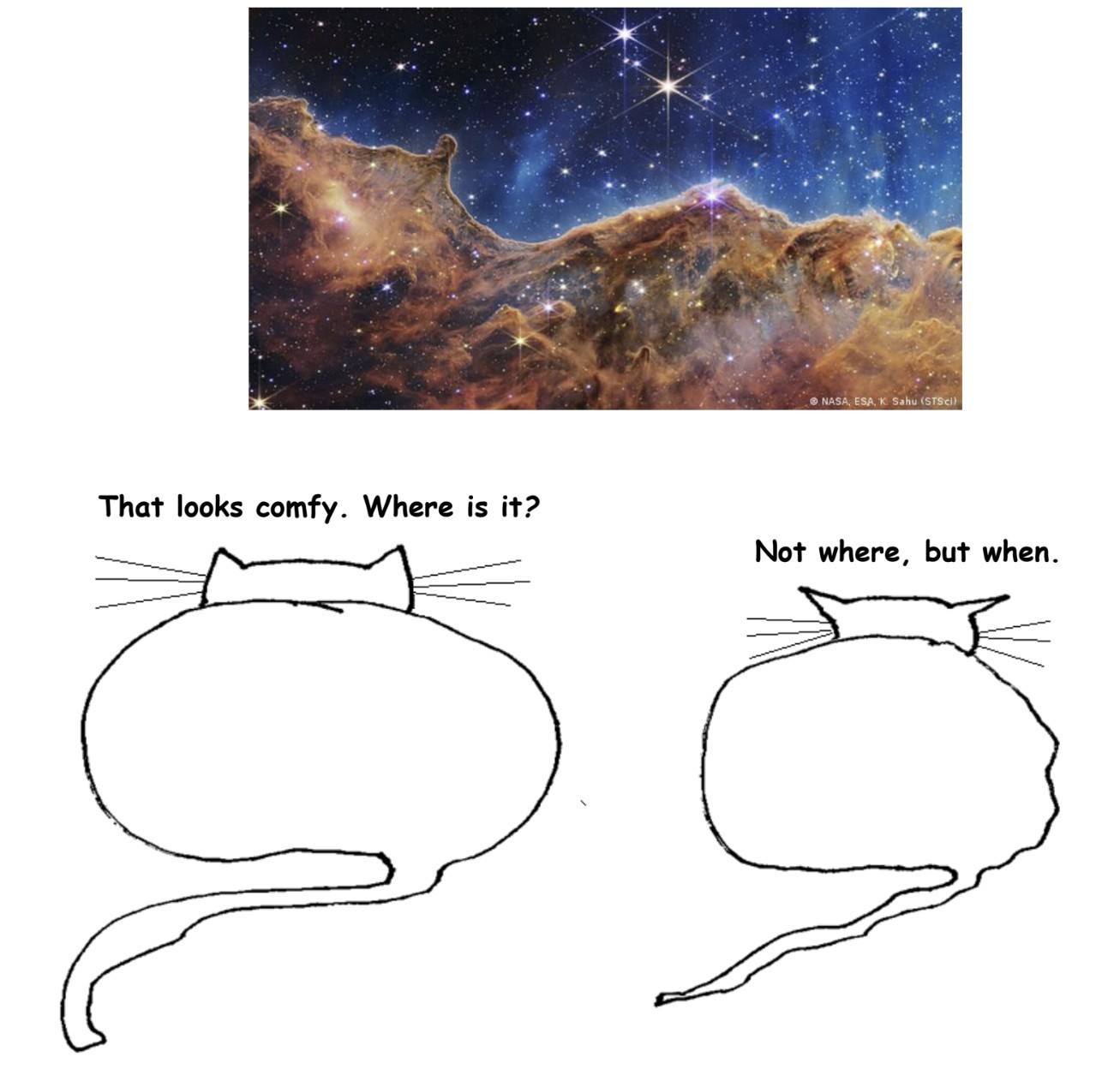

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

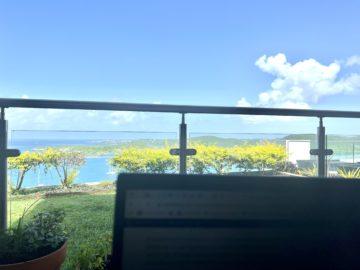

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.