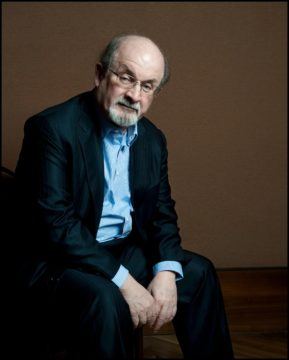

“On Friday morning, the author Salman Rushdie was stabbed in the neck as he stood onstage at the Chautauqua Institution, in western New York, where he was scheduled to give a lecture. The motivations of his attacker were not immediately clear, but Rushdie—one of the most celebrated contemporary writers—had lived under the threat of violence for decades. In 1989, the year after Rushdie published “The Satanic Verses,” a novel that imagines a fictional version of the Prophet Muhammad, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a decree, or fatwa, calling for Rushdie’s death.” —The New Yorker, 8/12/2022

______________________________________________

Last Day of Federíco García Lorca

“The writer died while mixing with the rebels, these are natural accidents of war . . .”

—Spanish Dictator Francisco Franco, Authoritarian

“The country has to toughen up … part of the problem …is nobody wants to hurt each other anymore, right?”

— US president, Donald Trump, Authoritarian

…….. Federico in pajamas and blazer died at night

…….. wearing the sudden-death clothes of a poet killed

…….. because there’s nothing more dangerous to despots

…….. than an artist who tells the day’s truth

…….. because some force within insists.

…….. Accepting death for being one’s self

…….. is life’s condition of being one’s self

…….. because to speak is to be.

…….. This condition applies to all in all times

…….. because nothing ever changes the insistence of love

…….. & witness under any sky or sun.

…….. Although the atmosphere of place and eras swings from

…….. heaven to hell on a dime before the head-count has time

…….. to blink, and because the intractable who paint Guernica

…….. or write Canto Libre or Satanic Verses

…….. (artists who dare) could well end with bullet-through-skull

…….. because, to a despot, silence is golden (long-lived or brief)

…….. because despots know that painters and poets,

…….. sculptors and dancers will always speak

…….. from momentary possession

…….. because they’ve found the straightway

…….. to brainsoul of human-kind,

…….. the place despots only enter

…….. by means of fear & blood

…….. which always mocks

…….. the divine

…….. Jim Culleny, 3/7/19

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

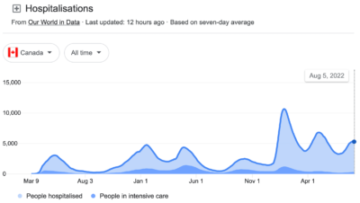

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back. The logic behind [interest] rate rises is that making the credit of the nations’ poor more, while they are already struggling with food and fuel bills, will make them in the long run better off.

The logic behind [interest] rate rises is that making the credit of the nations’ poor more, while they are already struggling with food and fuel bills, will make them in the long run better off. Last year, the particle physicist

Last year, the particle physicist  Cities that are attacked by nuclear missiles burn at such an intensity that they create their own wind system, a firestorm: hot air above the burning city ascends and is replaced by air that rushes in from all directions. The storm-force winds fan the flames and create immense heat.

Cities that are attacked by nuclear missiles burn at such an intensity that they create their own wind system, a firestorm: hot air above the burning city ascends and is replaced by air that rushes in from all directions. The storm-force winds fan the flames and create immense heat. The attack on Rushdie is a wake-up call for all of us who have a stake in free expression, which is all of us, period. While we do not yet know the motives of his attackers, it is hard to envisage a scenario in which this brazen, premeditated attack, the first in memory targeting a writer at a literary event in the United States, had nothing to do with Rushdie’s words and ideas.

The attack on Rushdie is a wake-up call for all of us who have a stake in free expression, which is all of us, period. While we do not yet know the motives of his attackers, it is hard to envisage a scenario in which this brazen, premeditated attack, the first in memory targeting a writer at a literary event in the United States, had nothing to do with Rushdie’s words and ideas. The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.)

The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.) One of the stranger sights on the University College London campus is the clothed skeleton of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Stranger still is that a waxwork head sits on its shoulders, where Bentham’s own head should be, as per his will. Meanwhile, his preserved head is elsewhere – his friends thought it looked too grotesque for display, and commissioned the waxwork one instead. Legend has it that Bentham’s real head was stolen by some students from King’s College London as a prank against their University College rivals, and a ransom demanded for returning it. Apparently, this was eventually paid up, and the head was returned.

One of the stranger sights on the University College London campus is the clothed skeleton of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Stranger still is that a waxwork head sits on its shoulders, where Bentham’s own head should be, as per his will. Meanwhile, his preserved head is elsewhere – his friends thought it looked too grotesque for display, and commissioned the waxwork one instead. Legend has it that Bentham’s real head was stolen by some students from King’s College London as a prank against their University College rivals, and a ransom demanded for returning it. Apparently, this was eventually paid up, and the head was returned.