Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker:

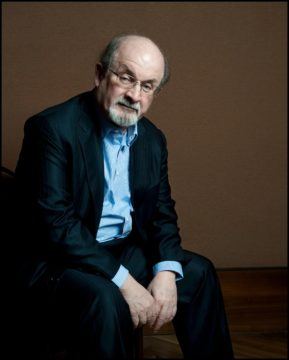

The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.)

The terrorist assault on Salman Rushdie on Friday morning, in western New York, was triply horrific to contemplate. First in its sheer brutality and cruelty, on a seventy-five-year-old man, unprotected and about to speak—doubtless cheerfully and eloquently, as he always did—repeatedly in the stomach and neck and face. Indeed, we accept the abstraction of those words—“assaulted” and “attacked”—too casually. To try to feel the victim’s feelings—first shock, then unimaginable pain, then the panicked sense of life bleeding away—to engage in the most moderate empathy with the author is to be oneself scarred. (At the time of writing, Rushdie is reportedly on a ventilator, with an uncertain future, the only certainty being that, if he lives, he will be maimed for life.)

Second, it was horrific in the madness of its meaning and a reminder of the power of religious fanaticism to move people. Authorities did not immediately release a motive for the attack, but the dark apprehension is that the terrorist who assaulted Rushdie was a radicalized Islamic militant of American upbringing—like John Updike’s imaginary terrorist in the novel “Terrorist,” apparently one raised in New Jersey—who was executing a fatwa first decreed by Ayatollah Khomeini, in 1989, upon the publication of Rushdie’s novel “The Satanic Verses.” The evil absurdity of the death sentence pronounced on Rushdie for having written a book actually more exploratory than sacrilegious—in no sense an anti-Muslim invective, but a kind of magical-realist meditation on themes from the Quran—was always obvious. (Of course, Rushdie should have been equally invulnerable to persecution had he written an actual anti-Muslim—or an anti-Christian—diatribe, but, as it happens, he hadn’t.)

More here.