Steven Petrow in The New York Times:

Shortly after my parents died in 2017, I nearly lost custody of my dog, Zoe, in my divorce. When we were reunited, I remember telling her firmly, “You cannot die now,” even though she had just turned 15. Not long after, the vet told me that new lab work indicated kidney failure. I was quite glad then that Zoe couldn’t talk, at least not in the traditional sense. We had no painful discussions about quality-of-life issues or end-of-life concerns.

Shortly after my parents died in 2017, I nearly lost custody of my dog, Zoe, in my divorce. When we were reunited, I remember telling her firmly, “You cannot die now,” even though she had just turned 15. Not long after, the vet told me that new lab work indicated kidney failure. I was quite glad then that Zoe couldn’t talk, at least not in the traditional sense. We had no painful discussions about quality-of-life issues or end-of-life concerns.

I approached her final chapter with intention and indulgence, which is to say I followed her lead. I fed her whatever and whenever she wanted. I let her decide whether we’d go for short walks or longer ones. Before I went to bed, I made sure Zoe had settled into hers. Even as I prepared to lose her, I found myself exulting in our days together. When she died, I consoled myself with the thought that she was never mine to begin with; I was lucky to have known her; we only have anyone we love for a short time.

As it turns out, it’s much easier to practice spiritual detachment from a Jack Russell terrier who is gone than from my younger sister, Julie, who is here, and called later that same year to tell me she had ovarian cancer. It was Stage 4, she said, as bad as it gets. Julie was 55, a lawyer and executive, a wife, and the mother of two daughters, 17 and 21.

More here.

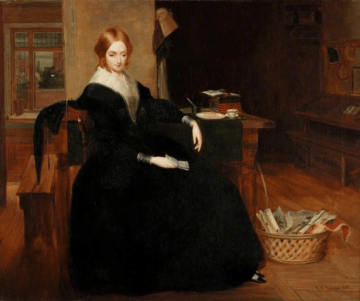

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a  Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,  I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman. Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze.

Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze.