Here are two quatrains by two famous Urdu poets – Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Sahir Ludhianvi – who have opposing views of a beloved’s memory. They were contemporaries, though Faiz was about ten years older. Faiz lived and wrote in Pakistan and was a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. He was a Communist and was thrown in prison for that reason. Sahir lived and wrote mostly in India, though for a brief period he was in Lahore and fled that place for India when, he too, was accused of being a communist. He was also a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. Both wrote eloquently and passionately. There the similarities end. Faiz wrote of love with optimism and hope – he was going to be successful in love. Sahir wrote in gloomy terms and with a sense of self-pity – love was not all roses for him.

In these two, very famous quatrains of theirs, one can see the difference between them. Faiz sees the lost memory of a beloved as a soothing breeze, as an onset of growth, as a balm to his fevered brow; Sahir saw love as happiness quickly leading to grief, as a flower whose thorns would beset him, soon. —Translator’s Note

___________________________________

Faiz Ahmed Faiz:

Last Night Your Lost Memory

Last night your lost memory crept into my heart

As in a wasteland, spring blossoms quietly

As in a desert, the zephyr sways gently

As to a dying man, relief comes, unexpectedly.

………………………… §§§

Raat yun dil mein teri, khoyi hui yaad aayi

Raat yun dil mein teri, khoyi hui yaad aayi

Jaise viraane mein chupke se bahaar aa jaye

Jaise sahraon mein haule se chale baad-ae-naseem

Jaise bimaar ko be-wajaah quraar aa jaaye

………………………… §§§

Sahir Ludhianvi

I picked a few flowers of happiness

I picked a few flowers of happiness

And for ages I was sunk in grief

Meeting you brings me happiness, yet

After meeting you, I remain in grief

………………………… §§§

Chand kaliyāñ nashāt kī chun kar

chand kaliyāñ nashāt kī chun kar

muddatoñ mahv-e-yās rahtā huuñ

terā milnā ḳhushī kī baat sahī

tujh se mil kar udaas rahtā huuñ

………………………… §§§

Translations by Ajit Dutta

What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility.

What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility.

When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study

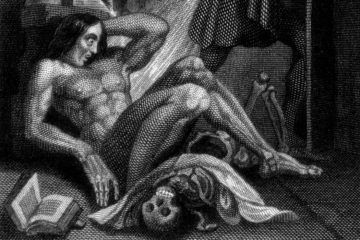

When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study  Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.”

Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.” As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away.

As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away. In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL.

In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL. D

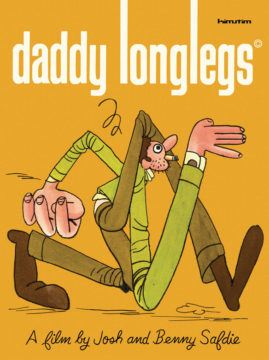

D Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s  “We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains.

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains. Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election.

Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election. More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself.

More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself. Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death.

Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death. As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that

As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that  Why do people keep falling for hoaxes?

Why do people keep falling for hoaxes? All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs.

All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs.