Stephanie Bastek in The American Scholar:

In pursuit of the natural laws of the universe, human beings have accomplished remarkable things. We’ve outlined the principles of gravity and thermodynamics. We’ve built enormous machines to dig into the deepest parts of the Earth, to understand what happens at the shortest quantum distances, and equally large machines to take pictures of the most distant parts of the cosmos. Still, there remain a number of foundational gaps in our knowledge—gaps that have allowed some wild ideas to take root. Some scientists hypothesize that, with every decision we make, our universe forks into multiverses, that consciousness arises from the quantum movements of microtubules, that the universe itself is conscious, or that there is this cat in a box and not in a box at the same time. These ideas, and related big questions about the nature of the universe, are the subject of particle physicist Sabine Hossenfelder’s new book, Existential Physics. In it, she argues that many of these far-out theories, put forward without evidence, are on par with religious belief. Physics, she contends, does not yet provide the answers to all of our questions—and it’s doubtful that it ever will.

In pursuit of the natural laws of the universe, human beings have accomplished remarkable things. We’ve outlined the principles of gravity and thermodynamics. We’ve built enormous machines to dig into the deepest parts of the Earth, to understand what happens at the shortest quantum distances, and equally large machines to take pictures of the most distant parts of the cosmos. Still, there remain a number of foundational gaps in our knowledge—gaps that have allowed some wild ideas to take root. Some scientists hypothesize that, with every decision we make, our universe forks into multiverses, that consciousness arises from the quantum movements of microtubules, that the universe itself is conscious, or that there is this cat in a box and not in a box at the same time. These ideas, and related big questions about the nature of the universe, are the subject of particle physicist Sabine Hossenfelder’s new book, Existential Physics. In it, she argues that many of these far-out theories, put forward without evidence, are on par with religious belief. Physics, she contends, does not yet provide the answers to all of our questions—and it’s doubtful that it ever will.

More here.

Inside a soundproofed crate sits one of the world’s worst neural networks. After being presented with an image of the number 6, it pauses for a moment before identifying the digit: zero.

Inside a soundproofed crate sits one of the world’s worst neural networks. After being presented with an image of the number 6, it pauses for a moment before identifying the digit: zero.  We’ve got the Internet all wrong. Its raison d’être is not, as Mark Zuckerberg claims for his own corporation, to “strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together.” To the contrary, the Internet is a pernicious disease. It is—as Justin E.H. Smith argues in his new book, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is—thoroughly “anti-human.”

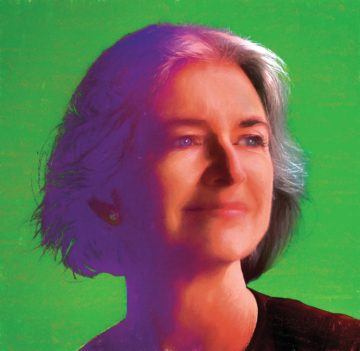

We’ve got the Internet all wrong. Its raison d’être is not, as Mark Zuckerberg claims for his own corporation, to “strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together.” To the contrary, the Internet is a pernicious disease. It is—as Justin E.H. Smith argues in his new book, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is—thoroughly “anti-human.” Very few writers in the twenty-first century are polymaths of the sort that previous centuries sometimes spawned – those who knew about all the subjects that mattered at the time, while still producing original work. Specialisation and the multiplication of fields and subfields of research, in both the humanities and the sciences, has rendered such breadth nearly impossible. Siri Hustvedt, however, is an exception: she is a polymath for our times, fluent in multiple specialised discourses, but whose mode is artistic.

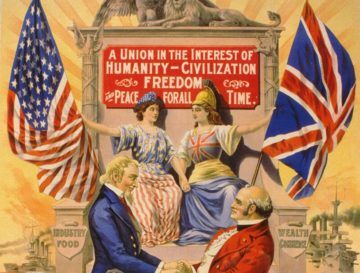

Very few writers in the twenty-first century are polymaths of the sort that previous centuries sometimes spawned – those who knew about all the subjects that mattered at the time, while still producing original work. Specialisation and the multiplication of fields and subfields of research, in both the humanities and the sciences, has rendered such breadth nearly impossible. Siri Hustvedt, however, is an exception: she is a polymath for our times, fluent in multiple specialised discourses, but whose mode is artistic. In the United States, the political baptism of the non-elites to the hegemonic mission happened in the years between 1920 and 1960. Mass culture in those crucial years paved the way for a patriotic politics built around U.S. military prowess, massive expansion of literacy and lifestyle, the phobias of the Red Scare and Jim Crow, and commercial success across the globe. By the midcentury, anti-communism produced a coordinated ideological effort at cohesion. Elites recruited the political aspirations of working-class and middle-class voters into the cause of American supremacy, framing the export of American consumer capitalism as the triple gift of sacred freedom, true democracy, and general prosperity. The Hollywood studio system picked up the plots of late-Victorian adventure genres, adapting them to the worldview of U.S. supremacy and global centrality.

In the United States, the political baptism of the non-elites to the hegemonic mission happened in the years between 1920 and 1960. Mass culture in those crucial years paved the way for a patriotic politics built around U.S. military prowess, massive expansion of literacy and lifestyle, the phobias of the Red Scare and Jim Crow, and commercial success across the globe. By the midcentury, anti-communism produced a coordinated ideological effort at cohesion. Elites recruited the political aspirations of working-class and middle-class voters into the cause of American supremacy, framing the export of American consumer capitalism as the triple gift of sacred freedom, true democracy, and general prosperity. The Hollywood studio system picked up the plots of late-Victorian adventure genres, adapting them to the worldview of U.S. supremacy and global centrality. Two Chinese psychologists talk about divorce, stockpiling and crying into your mask.

Two Chinese psychologists talk about divorce, stockpiling and crying into your mask. Suzanne Kahn at the Roosevelt Institute:

Suzanne Kahn at the Roosevelt Institute: Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar: In the course of his book, Calvo describes many experiments that reveal plants’ remarkable range, including the way they communicate with others nearby using “chemical talk”, a language encoded in about 1,700 volatile organic compounds. He also shows how, like animals, they can be anaesthetised. In lectures, he places a Venus flytrap under a glass bell jar with a cotton pad soaked in anaesthetic. After an hour the plant no longer responds to touch by closing its traps. Tests show the plant’s electrical activity has stopped. It is effectively asleep, just as a cat would be. He also notes that the process of germination in seeds can be halted under anaesthetic. If plants can be put to sleep, does that imply they also have a waking state? Calvo thinks it does, for he argues that plants are not just “photosynthetic machines” and that it’s quite possible that they have an individual experience of the world: “They may be aware.”

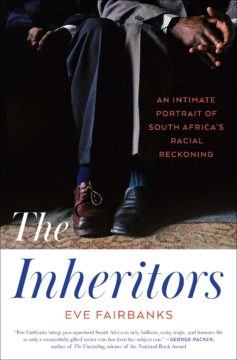

In the course of his book, Calvo describes many experiments that reveal plants’ remarkable range, including the way they communicate with others nearby using “chemical talk”, a language encoded in about 1,700 volatile organic compounds. He also shows how, like animals, they can be anaesthetised. In lectures, he places a Venus flytrap under a glass bell jar with a cotton pad soaked in anaesthetic. After an hour the plant no longer responds to touch by closing its traps. Tests show the plant’s electrical activity has stopped. It is effectively asleep, just as a cat would be. He also notes that the process of germination in seeds can be halted under anaesthetic. If plants can be put to sleep, does that imply they also have a waking state? Calvo thinks it does, for he argues that plants are not just “photosynthetic machines” and that it’s quite possible that they have an individual experience of the world: “They may be aware.” It was nothing short of a miracle — that was what South African schoolchildren were taught when Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, in the country’s first fully democratic elections. Apartheid, the brutal system of white minority rule that made South Africa a global pariah, was over. As Eve Fairbanks writes in “The Inheritors,” her new book about the decades before and after that transition, its miraculousness “was like mathematics, amazing but incontrovertible.”

It was nothing short of a miracle — that was what South African schoolchildren were taught when Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, in the country’s first fully democratic elections. Apartheid, the brutal system of white minority rule that made South Africa a global pariah, was over. As Eve Fairbanks writes in “The Inheritors,” her new book about the decades before and after that transition, its miraculousness “was like mathematics, amazing but incontrovertible.” MILMAN PARRY

MILMAN PARRY It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.”

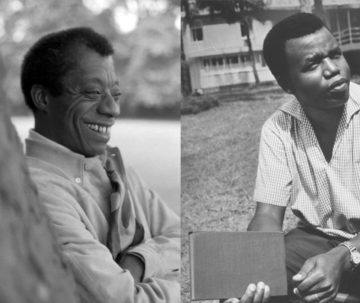

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.” Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001  It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the

It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the