by Charlie Huenemann

A man rides an empty suit. The suit tells others what to think of the man, though it would not fit him. The man does not control the suit, but merely takes a ride upon it, come what may.

In his twenties, Franz Kafka composed a long story, “Description of a Struggle”, which remains one of his most enigmatic works. It follows a dream-like logic from a party, to a stroll through Prague, to an encounter with “a monstrously fat man” being borne in a litter by four naked men, to a supplicant once known by the fat man who prayed by bashing his own head against the stone floor of a church, to a final scene on a mountaintop, where a stabbing takes place, though it does not seem to be very consequential. The end.

Max Brod thought it was a work of genius, though John Updike thought it was adolescent posturing. (¿Por qué no los dos?) Like all of Kafka’s works, it shows up on your doorstep like a locked desk that you are sure contains something you need, but the key is locked inside it; and when you finally bash the desk open, you find your own corpse with a toe tag reading “GUILTY OF BREAKING THE DESK”. Maybe some of the strange imagery Kafka himself could neither explain nor control, maybe some of it spoke of his own secrets, maybe all of it is an existential parable.

One thing is for sure: the story shatters in every way. We might expect a story with a beginning, middle, and end: nope. We might expect some clarity about just whose story it is: nope. We might expect facts to stay fixed, or people to inhabit their own bodies: nope. We might expect some thread of consistency, conversations that make even minimal sense, words of wisdom that do not culminate in irrelevant banalities. Nope, nope, nope. That the work is offered as a story, and even as a description, is an exaggeration. It’s something, all right, and we may try to read it as a story, but the damned thing will not cooperate. It keeps falling apart the more we try to hold it together, like a human life, come to think of it.

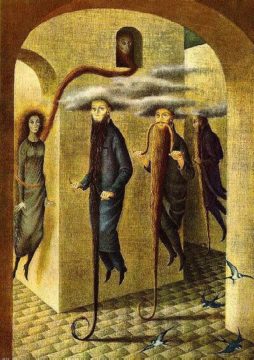

Much of the story concerns the companionship between the initial narrator and his acquaintance. But I don’t suppose that they are separate individuals. The acquaintance might be the narrator’s public self, or his shadow, or his empty suit; or perhaps the narrator is the acquaintance’s better judgment, or his conscience; or maybe the two of them and the supplicant and maybe the fat man too (and hell why not throw in the four naked guys as well) are all different voices struggling to put a self together, and the resultant “story” is not so much a description of this struggle so much as a casualty from it. In any case, the next time your friends complain of suffering from imposter syndrome, tell them that Kafka takes that elevator all the way down to the parking garage. For Kafka, it takes an imposter to worry about being anything.

The struggle, I think, is the effort of maintaining a sense of a story when the unwritten truth — the utter scriptlessness of experience — protests screamingly against it. The coherence of our experience, from the selves we narrate into being to the natural facts that figure so heavily into our plans, is an hypothesis, a proposal or policy we live by just as we decide to ignore everything that does not fit. Once we decide to ignore the jackhammering in the street outside, we can enjoy a nice, quiet meal.

According to the monstrously fat man, the supplicant made this observation of the people crossing the town square on a windy day:

The ladies and gentlemen who should be walking on the pavement are floating. When the wind falls they stand still, say a few words, and bow to one another, but when the wind rises again they are helpless, and their feet leave the ground at the same time. Although obliged to hold on to their hats, their eyes twinkle gaily enough and no one has the slightest fault to find with the weather. I’m the only one who’s afraid.

We float, gaily enough, and are carried about on winds that we generally ignore. Why we say what we say, why some problem engages our attention, why we move our arms the way we do or sit in the postures we adopt — these are all unknown to us in the moment, and it is in these gusts of whim that we carry out the sequences of behavior we package together as our lives. A story that tries to give a more accurate sense of the senseless and arbitrary gestures we make will seem to be no story at all, but rather a long and rambling episode of adolescent posturing. Such a story is completely useless for living a life, as it generates none of the fiction we require to stay afloat. Kafka names the second section of his work “Diversions or Proof that it’s Impossible to Live”.

Kafka must have decided eventually that a revelation this jarring — the revelation that we can live only in fictional worlds — is best approached sideways, not directly. He went on to tell stories that are more recognizable as stories, even if they were still filled with transformations into bugs and implacable guards of dead-ends and deadly penalties for harmless infractions. His fictions ingeniously destabilize the fictions of his readers; or, like his four naked men, they carry his monstrously fat readers down to the river and there drown them (and drown alongside them). Some truths are best seen when seen from the corners of one’s eye. As Kafka wrote to Brod upon completing the manuscript, “what pleases me most about the novella, dear Max, is that it’s out of the house”. It’s hard to live with such things.