by Rafaël Newman

For John Duffy (November 5, 1963—March 3, 2022)

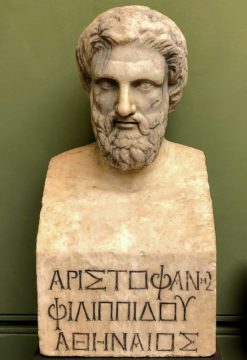

…great confusion ensued, and everyone was compelled to drink large quantities of wine. Aristodemus said that Eryximachus, Phaedrus, and others went away—he himself fell asleep, and was awakened towards daybreak by a crowing of cocks, and when he awoke, the others were either asleep, or had gone away; there remained only Socrates, Aristophanes, and Agathon, who were drinking out of a large goblet which they passed round, and Socrates was discoursing to them, compelling the other two to acknowledge that the genius of comedy was the same with that of tragedy, and that the true artist in tragedy was an artist in comedy also. To this they were constrained to assent, being drowsy, and not quite following the argument. And first of all Aristophanes dropped off, then, when the day was already dawning, Agathon. Socrates, having laid them to sleep, rose to depart; Aristodemus, as his manner was, following him. At the Lyceum he took a bath, and passed the day as usual.

*

Meanwhile, chez Agathon, as the sun rose higher in the sky and began to slant through the windows of the room in which the drinking party had been held, it tickled the host’s nose where he lay, disheveled in a corner. The tragedian sat up, sneezed abruptly, and gazed blearily around him. When he noticed Aristophanes’ feet protruding from beneath a pile of cloaks in the far corner, his head under one of the banqueting couches, he called out gingerly to his one remaining guest:

“Aristophanes.”

No answer. Now louder:

“Aristophanes!”

The comic playwright groaned weakly, turned face downwards under the couch, and resumed his snoring.

Agathon rose shakily to his feet, approached Aristophanes, kneeled on the floor beside him, leaned as close to his ear as the furniture would allow, drew a breath, and exclaimed brightly:

“BREKEKEKEX KOAX KOAX!!!”

The report from Aristophanes’ head hitting the underside of the couch was accompanied by an admirably fluent stream of invective. Having made uncomplimentary mention of his host’s wardrobe, affective predilections, and rhetorical style, the comic playwright extricated his upper body from its makeshift cubicle and sat up.

“I see you’re awake,” he hissed.

“Actually,” said Agathon, “I haven’t been to sleep at all.” He rocked back on his heels and made himself reasonably comfortable at Aristophanes’ side. “I couldn’t stop thinking about what Socrates was saying.”

“You’ll have to refresh my memory,” Aristophanes said acidly. “Once we had broken our silly vow of temperance, I think I put away the better part of a krater. You know how I get around dancing girls.” He scratched himself lavishly under his robe. “Or wait, do you mean that rubbish about old Diotima and her true love of the immortal and the beautiful and the everlasting possession of a really nice pair of sandals and blah blah blah?”

“No, no, no, I’ve heard Socrates’ whole idealist mission to the troglodytes a million times. And I’m not surprised it hasn’t taken with you, you miserable old cave-dweller.” He swatted Aristophanes playfully, very near the spot that had just been enjoying the comedian’s therapeutic attentions, and was rewarded with a gratifying growl of warning. “I mean that last business, saying that the same person could do both tragedy and comedy, because somehow both forms are animated by the same spirit, or daimon, or something like that. I’ve actually never heard him mention anything of the kind before.”

“Good thing too.” Aristophanes leaned to one side briefly, just far enough to release a comfortable fart. “Because it makes no sense. Can you see me staging a tragedy? Can you imagine me writing one? And what would it be about anyway, a frog with a foot injury? Fain would I hop and gambol in the happy grove! / But nay, alas, the gods begrudge me my delight / and make a tripod of this erstwhile four-legg’d wretch!”

When Agathon had recovered from the paroxysms of revulsion and delight occasioned by Aristophanes’ impromptu mixed-media performance, he fortified himself with the blend of barley, wine, and cheese left in a nearby goblet and continued. “Obviously I agree it’s a ridiculous idea in any practical sense. I just think Socrates meant something else. Something not unlike what you were getting at in your speech last night.”

Aristophanes laughed. “You do know I was joking, don’t you, sweetheart? You mean those self-satisfied, roly-poly, eight-limbed androgynes? All that bollocks about the envy of the gods and Zeus cleaving them in twain with his thunderbolt, and the mutilated halves ever after mooning about, looking for their severed selves? How gullible are you?”

“Yes of course I realize it was a comic set piece,” said Agathon with an impatient flick of his perfumed hair. “I just mean he was getting at the same basic idea as you were, that it might be possible for one individual to contain certain apparently opposite qualities, like humor and despair, irreverence and piety, the tragic and the comic, the male and the female…”

“Those last two aren’t as opposite as you might think,” muttered Aristophanes. “Just ask Euripides.”

“…the philosophical and the military,” Agathon continued, undeterred, “cowardice and bravery, Athens and Sparta…”

“Careful,” warned the comedian, “you never know who might be listening.”

“Could you stop cracking jokes for a second and hear me out? It’s as if Socrates were taking back all that stuff about the middle way and yearning for perfection, that whole Diotima crap about the mean between the two and all the rest of it, and proposing something new, something a little more complex, a little less…dimorphous.”

“Ooh, harken to madam.”

“Shut up, will you? I’m trying to think.”

“I’ve warned you about that. Tragedians should never think, they should just feeeeeel. That’s how they come up with all their florid nonsense. D’you suppose Aeschylus could’ve ever written about oxen standing on his tongue and people keeping lions as house pets if he’d stopped to think about it?”

“What I mean is, I think Socrates is suggesting that tragedy and comedy are not that different, not that opposite, as you quite rightly suggested regarding women and men (yes, I heard you), but that there is always a little bit of the other in each of them: the satyr play concluding the tragic trilogy, obviously, but also all of those humiliations and painful lessons dealt at the hands of ostensible friends in comedies. And I think he’s also saying that there might be more than just two poles available to us in any case. To our characters.”

“Like his business about the three souls, and the three cities, or whatever?”

“Yes, sort of, though I don’t think he has that all worked out yet. But also, not exactly the same, because whereas in that tripartite psycho-political model he has the various components of the soul, and the corresponding castes in the city—the reason, the spirit, and the appetite, on the one hand, and the rulers, the helpers, and the producers, on the other—more or less constantly at war with one another, last night’s discussion suggested a more harmonious co-existence of opposites—or rather, of juxtaposed, potentially conflicting attitudes.”

Aristophanes, for once, was speechless. He had never heard his friend talk like this before. Agathon sounded so…sophisticated. Like a sophist; very nearly Sophoclean.

“Actually, it’s more like the vision Alcibiades said he had had of Socrates: that the man isn’t particularly prepossessing from the outside, that he’s rather squat and homely in fact; but that if you could get a look inside of him, you’d see something else entirely, something much richer, something much more beautiful.”

“Ghastly thought.” Aristophanes shuddered. “I wouldn’t pick the pimples on his back, much less peer up his bum!”

“Not literally inside him, obviously, you idiot. More like sort of symbolically, like what’s really inside his character, or even in his soul, as opposed to what’s on his face, or on the surface of him: a look inside him at all those dozens of tiny golden statuettes or however Alcibiades put it, a wonderful whole little museum of gorgeous, mysterious artifacts.” Agathon paused for a moment and closed his eyes in reverie. “But not all of them the same, if that’s how Alcibiades meant it. The way I imagine it, inside certain of us, or maybe inside just one of us, the best of us, there are all these little precious figures; but they’re all different, if each one equally valuable, each the effigy of a different god, or daimon. There’s one for instance that represents the strong, impetuous, spirited, bombastic, strategic aspect of this person’s character; it’s a little likeness of Alcibiades himself, if you like. And there’s another that stands for irreverence, and ribaldry, and humor, and rebelliousness, and skepticism: that might actually look a lot like you, my darling.” At this, Aristophanes smiled crookedly, in spite of himself. “And then there’s still another one, of course—or rather, with any luck—that resembles our admirable, belovèd, maddening Socrates, and which represents wisdom, and perseverance, and humility, and irony—as well as hope.”

Agathon had risen to his feet, swaying slightly, arms outstretched, a beatific look on his pretty face.

“Don’t tell me you’re going to sing now,” Aristophanes groaned. “That might kill me.”

But it was too late. Agathon was already tapping his foot in time to the series of iambic trimeters he had begun intoning:

Argus Panoptes, ever vigilant, safeguard

Of Io’s virtue with his hundred tireless eyes;

Three-headed Cerberus; Briareus, whom we call

Aegeon, who with hundred arms and fifty heads

Gave succor to the father god, that time he tried

With Titans for the title to the topmost throne…

Here Aristophanes emitted an involuntary grunt of admiration for Agathon’s prosodic bravura. The poet smiled in recognition of the grudging praise and continued:

Such wights are manifold, and terrible; and yet

Their prodigy is bald and patent to the eye,

While mine is cached within me, all the mightier

As recondite, and ready to be blent anew

At any chance: now biting censure, now sweet praise,

Now bawdy scansion, now a tow’ring metropole

With all its ways and welter, bane and boons,

Disgorging fully blown from out my head as once

The virgin, warring wise, stepped forth from Zeus the king.

And thus provided with this hidden panoply,

No task, no artifice can fail me, but I stride

From deed to deed with equal skill; for such a one,

The comic and the tragic arts are children’s toys,

And changeable as temper and the time demand.

Nor battlefield, nor ballot box, nor building site

But I have paced its length and traced its lofty form,

And left it better than it was ere I drew near.

These are my gifts, my armor, and my chancery,

All housed within; and do you reckon them in strife,

As ancient enemies or sprung from feuding clans,

You err: for I have one who keeps a sturdy peace,

A steward of my place and chancellor at home,

A trusted major domo and my lord withal,

Preceptor of my youth and tutor of my age—

And that is Love…

Aristophanes had hidden his face in his sleeve; his shoulders rose and fell gently as he sobbed. When he had calmed himself, he turned to face Agathon again, and, his anger at the loss of his customary sardonic composure tempered by frank adulation, whispered: “But someone like that…well, they would surely be at risk for the envy of the gods: those peevish, vengeful, spiteful bullies. As were my androgynes.”

“Perhaps,” Agathon admitted with a shrug. “But it might be worth the risk, just to have enjoyed gifts like those.”

The two friends were silent, grieving, preposterously, over the fate of an imaginary being.

At length Aristophanes spoke. “And do you suppose that a person like that might one day exist? Might already live among us?”

“Maybe one day,” said Agathon ruefully. “At any rate, they would certainly have to be…

*

With thanks and apologies to B. Jowett

and love from RΔF