by Nicola Sayers

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self, Pinterest, Instagram (but not Facebook, which lacks Instagram’s curatorial function): these are all avenues through which a fanatical need to record is fed.

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self, Pinterest, Instagram (but not Facebook, which lacks Instagram’s curatorial function): these are all avenues through which a fanatical need to record is fed.

There are similarities between us twenty-first century scrapbookers and our forerunners. Walter Benjamin viewed the collector — and what is the scrapbooker if not a collector of memories, ideas, images? — as a kind of revolutionary. By taking things out of their old contexts, and repurposing them according to a new, personal, logic, the collector achieves a kind of renewal of the old world. But there is nonetheless an anxiety underlying the scrapbooker’s work. As Benjamin writes in The Arcades Project, the collector is ‘struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which the things of the world are found.’ Like our predecessors, we digital scrapbookers, are driven – in our desire to record and to organize – by a kind of existential urgency: an impossible desire to capture the ephemeral, to articulate the ineffable. And like them, we too cling to the touchingly grandiose sense that somehow, via our paltry efforts, existence itself might be single-handedly sewn together into a meaningful pattern. The underlying fear of all scrapbookers, though, is not only the disorder and transience of existence, but the disorder and transience of the self. The unspoken mantra: I record, therefore I am.

What is also true now, as it was then, is that you do not need the whole of the scrapbooker’s collection to make sense of their particular longings. If viewed carefully enough, any one page in a scrapbook, any one of these virtual fragments, reveals clues to the whole. Take, for example, an email, sent from me to myself, which I recently came across when I was looking for a passage from the book Stoner by John Williams, so searched my inbox. This may seem a strange approach, but I am in the habit of writing out and emailing myself striking passages in books that I am reading – yet more points in the vast and disparate constellation which is my digital scrapbook of sorts. I only seldom look these emails up, and often can’t remember what search terms to use, but it reassures me to know that they are there. Meaningful missives, smuggled bits of beauty, nestled in among the thousands of organizational emails and unwelcome advertisements from companies to which I have unwittingly given my details. I am perhaps a lot like my father, who periodically buys himself a Christmas present, which he takes great care in wrapping elegantly and placing under the tree – a gesture presented as a joke but which I suspect is on some level an effort to ensure that he gets at least one gift that he actually wants.

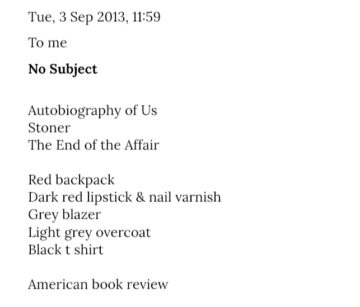

On this occasion, though, I did not find the passage in question. Instead, I came across the following ( also part of the same instinct to record what needs remembering, by whatever means available).

Three novels. A coming of age story about two friends in 1960s California, which I never in the end read; the aforementioned Stoner, which is perhaps best described simply as the story of a life; and Graham Greene’s tale of, well, the end of an affair. Then, a seamless transition: a list of clothes and beauty products. Things I meant to buy? I see that I sent the email to myself at the start of September, the time of year when I am usually brimming with back-to-school anticipation (even in the few years that I have not been in school). In 2013, it looks as though I was plotting my autumn wardrobe, almost a pastiche of campus fashion. Then another transition. American Book Review. A literary journal specializing in reviews of neglected or marginalized works of literature or criticism. Presumably a journal that had caught my eye, or for which I was trying to pitch.

I am struck by the truth, exposing as it is, of this list. The fragments revealing the whole. I’d even venture that if you had to summarize a life you could do worse than going off one of these scraps. One could imagine an algorithm which, given any one of these little records, punched out an epitaph of sorts for the person in question. Based on my email to self, mine might read: Liked books, clothes and autumn. Literary pretensions. Teenager at heart. And it wouldn’t be wrong.

But there are some crucial differences between us twenty-first century scrapbookers and our forerunners, too. Walter Benjamin comments that the collector, in forming her collection, is aiming to achieve a ‘peculiar category of completeness’. As he writes, again in The Arcades Project,

‘It is the deepest enchantment of the collector to enclose the particular item within a magic circle, where […] it turns to stone. Everything remembered, everything thought, everything conscious becomes socle, frame, pedestal, seal of his possession.’

Benjamin recognized that this desire — a desire for permanence, in essence — was never actually realized, or realizable. When he writes that ‘his collection is never complete; for let him discover just a single piece missing, and everything he’s collected remains a patchwork’, he is gesturing towards the inherent difficulty in attempting to encircle, to complete, what is inherently incomplete. That tension is what allows us to think of the work of the collector, of the scrapbooker, as utopian. The scrapbooker attempts a kind of cohesion of memory, of thought, of experience, which is both noble and impossible.

But an imitation of completeness used to be, nonetheless, at least within grasp. A physical scrapbook is a discrete thing. You can fill up the pages (even if most scrapbookers or journal keepers can attest to how seldom that happens). By contrast, these other virtual places of record-gathering are, by their nature, not only not finite: they actively tend towards proliferation — as, indeed, does the internet as a whole. Recently I was scrolling a word document on my phone as I was putting my four year old to bed. ‘Mummy’, he said, ‘the other day I asked Daddy: where do the car windows go when we pull them down?; and now I’m asking you: where do all the words go when they leave your phone?’ A few minutes later: ‘Mummy, will the words ever run out?’ That we use the verb ‘scrolling’ to describe the way we use our phones is striking: it is much like a scroll, albeit one with no beginning and no end. The work of the digital scrapbooker, then, if similar in motivation, is much harder than that of our quaint scrap-sisters of yesteryear. If they tried to tame a river, we are faced with an ocean.

Another difference between the virtual records of today and the scrapbooks of yesterday is, of course, their public nature. One of the things about the collector which most enchanted Benjamin was that the collector does not emphasize the ‘functional, utilitarian’ value of the things he collects, ‘but studies and loves them as the scene, the stage of their fate’ (‘Unpacking My Library’). But it is debatable if virtual records can ever entirely escape their ‘use’ value. Things like Instagram and Pinterest are, of course, public, even if only to our friends and acquaintances. But even emails to oneself, or indeed iPhone notes, are stored on the cloud and “read” by google. I don’t mean to get into the ethics of this, about which much has been written and much is felt, but I am interested in what this does to the act of recording. If the logic of recording, or collecting, information was always personal, it feels different when there is a third eye who is also busy narrativizing that same pattern. My sense that an algorithm might write my epitaph on the basis of my little records is less charming given that there is, today, an algorithm doing more or less that, even if we never see it.

Like others of my persuasion, I will continue my record-gathering practice; continue filling these disparate, virtual, scrapbooks of sorts, in addition to my physical journals and scrapbooks. I can’t not. Such is the need in those driven to record that the opportunities opened up by the internet are irresistible. But I know too, that with every new app that offers itself up as a shiny new home for all the fleeting inspirations we scrapbookers try desperately to gather, the anxiety will only increase. I record, therefore I am. Except that rather than being pulled back together through the act of recording, the scrapbooking ‘I’ is today only pulled further and further apart.