by Peter Wells

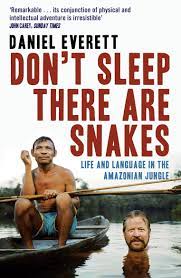

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Everett includes a harrowing description of a desperate journey to save the lives of his wife and daughter when they became seriously ill, and other incidents when his own life was in danger. He lovingly describes the sights and sounds of the rivers. He relates many anecdotes illustrating the culture of the Hi’aiti’ihi, and the relationships between them and the neighbouring populations. He draws lively thumbnail sketches of memorable characters he met.

He mentions, somewhat incidentally, his unsettled childhood and youth, with an allegedly alcoholic father. He reports that as a teenager he fell in love with, and married, the daughter of a local evangelical pastor, and turned his life around. He became a fervent Christian, and with his wife studied linguistics at the Summer Institute of Linguistics (now SIL International), a Christian non-profit organisation, whose main purpose is to translate the Bible into all the world’s languages.

In 1977 Everett and his wife Keren were charged by their church with the task, not primarily of preaching to the Hi’aiti’ihi (though they did try to share their faith with them) but of learning their language, Pirahã, well enough to translate the Bible into it. The story becomes intensely personal. Everett, a devout Chomskyan, found that his hero’s framework was unable to deal with many features of Pirahã. He began to publish his findings and became notorious for his challenge to Chomsky. He is now an eminent linguistician in his own right (currently Professor of Cognitive Sciences at Bentley, Massachusetts), but the controversy with Chomsky and his followers was acrimonious and, for the young linguist, distressing. Even more emotive is the story of his break with his church, as he slowly discovered that the Hi’aiti’ihi, whom he admired, had no need of Christianity. This in turn triggered the end of his marriage, and split his family.

In the second part of the book Everett picks up on some of the hints about the language and culture of the Hi’aiti’ihi mentioned in the first part, and develops his thesis that the culture of the Hi’aiti’ihi has influenced the grammar of their language, a suggestion that casts doubt on the theory that there is an identical ‘Universal Grammar’ embedded in all human minds. At this point the reader, who has been enjoying descriptions of quaint customs and exotic fauna mixed with biography, is suddenly plunged into the intricate details of linguistic theory, and the internecine atmosphere of academic controversy.

However, the melange of disparate themes found in ‘Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes’ is a madness in which there is method. The themes are interlinked in many complex ways, which Everett must have sensed intuitively would shed light on each other in a way a more obviously organised book, or set of books, would not have achieved. The same culture that affected Pirahã grammar in ways Chomsky had not anticipated also caused Everett to abandon his faith, and fractured his family. This unusual book raises a range of fascinating and important issues, such as the importance of field work in linguistic study, the origin of language, and even the secret of happiness.

As the young Everett began to examine Pirahã in the way the Summer Institute had taught him, following Chomskyan principles, he found that it was different from most languages, and even possibly from all others. Features that he had been taught to expect were absent, or minimal. For example, Pirahã lacks recursion – the ability of languages to embed elements within one another, as in ‘Bring the nails that Dan bought.’

In 2002, in the journal Science, Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and Tecumseh Fitch placed a great burden on recursion by labeling it the unique component of human language. They claimed that recursion is the key to the creativity of language, in that as a grammar possesses this formal device, it can produce an infinite number of sentences of unbounded length.

Pirahã also lacks ‘phatic’ communication – expressions like hello, goodbye, how are you, I’m sorry, you’re welcome, and thank you. According to Everett, it has no words for left or right, no numbers, no quantifiers, no comparatives, no perfect tenses, no specific colour terms, and an exceptionally small number of kinship terms: elder, sibling, son and daughter.

Many of these assertions have been challenged by linguisticians who have decided a priori that a human language must exhibit certain features. Chomsky has apparently labelled Everett a ‘charlatan,’ presumably trying to suggest that he has manufactured his findings about Pirahã in order to make a name for himself. But at this point the unusual composition of ‘Don’t Sleep‘ comes into its own and makes such accusations unsustainable. First, the stories of the hardships sustained by Everett and his family, which nobody doubts, illustrate how demanding the research was. To reach the Hi’aiti’ihi in the first place involves a dangerous journey in a small plane, or a long series of river trips. Everything needed for the life of a researcher, and for a Westerner to survive, has to be carried in. Once installed, the researcher has to work in intense heat and humidity, in primitive conditions, dripping with perspiration, constantly battling with disease and dangerous fauna, including poisonous snakes and insects. A river-bathe can be shared with piranhas, and a routine shopping errand by canoe can run into a giant anaconda. Everett and his (former) wife, by living and learning with its speakers, are the only people from the outside world who have got to grips with Pirahã, and until their opponents have faced the same vicissitudes, their objections will have no weight. On the whole, those who have dared the trip out to the Amazon in the hope of discrediting Everett’s claims have not succeeded in doing so. Indeed, Everett has carried his case on a number of issues, such as the Pirahã lack of numbers and specific colour terms, where independent researchers have been able to adjudicate.

Second, it is abundantly clear that when he first went out to the Maici, Everett had no intention whatever of subverting the Chomskyan system, any more than he intended to lose his religious faith. His 1983 doctoral dissertation (in Spanish, on the syntax of Pirahã) is based on Chomskyism. So ‘Don’t Sleep’ is the story of a man who lost two faiths – in Jesus, and in Chomsky, and the emotional wrench involved gives credence to his findings.

The first point to emerge from ‘Don’t Sleep‘ is that the investigation of language – as of anything else involving human beings, indeed, almost anything real – involves hands-on investigation of the subject. “You cannot, in my opinion,” Everett remarks in his lectures, stating the obvious, “do fieldwork without learning the language.” He cites Paul Postal’s dictum: ‘First, learn the language; second, test and generate hypotheses daily.’ In other words, he is at the opposite pole from the followers of Chomsky, who tend to decide what language must consist of from the security of their studies. This places them on the ‘prescriptive’ wing of the ‘descriptive-prescriptive’ spectrum.

Noam Chomsky (b. 1928, still an Emeritus Professor at MIT) is to be praised for his demolition of the Behaviourists, such as Skinner, who in his view reduced human beings almost to the status of animals, or automatons. His admiration for the innate linguistic capacity of human children is perhaps linked with his well-known humanitarian views. What sane person could drop napalm on such amazing beings? But he does not come well out of this story. He seems to suffer from professional jealousy and an unwillingness to re-examine his ideas, some of which have serious implications.

Noam Chomsky (b. 1928, still an Emeritus Professor at MIT) is to be praised for his demolition of the Behaviourists, such as Skinner, who in his view reduced human beings almost to the status of animals, or automatons. His admiration for the innate linguistic capacity of human children is perhaps linked with his well-known humanitarian views. What sane person could drop napalm on such amazing beings? But he does not come well out of this story. He seems to suffer from professional jealousy and an unwillingness to re-examine his ideas, some of which have serious implications.

If it is indeed the case that human languages must have recursion, and if Pirahã doesn’t have it, then the Hi’aiti’ihi are not human, or at best subhuman. But Everett, who has actually lived with them more than any other non-native apart from his wife, says,

I realised they don’t have a word for worry, they don’t have any concept of depression, they don’t have any schizophrenia or a lot of the mental health problems that we have, and they treat people very well. If someone does have any sort of handicap, and the only ones I’m aware of are physical, they take very good care of them. When people get old, they feed them.

To me, the Hi’aiti’ihi sound like human beings!

To be fair on Chomsky, he has not, as far as I know, suggested that the Hi’aiti’ihi are not human. His position is that, as the Hi’aiti’ihi are human, and human language always exhibits recursion, then Everett must be wrong. But the implication remains. If Everett is right about the Hi’aiti’ihi not having recursion, and Chomsky is right about recursion being an essential feature of human language, then the Hi’aiti’ihi are not human. As they manifestly are human, and pretty clearly don’t have recursion in their syntax, Chomsky must be wrong.

Chomsky has defended his position by saying, initially, that perhaps Pirahã does recursion invisibly, and, later, that recursion is a fundamental element of human language ability, which is not necessarily found in all human languages, or even in any of them – a response ridiculed by Everett:

One answer that Chomsky and others have given to my claim that Pirahã lacks recursion is that recursion is a tool that’s made available by the brain, but it doesn’t have to be used. But then that’s very difficult to reconcile with the idea that it’s an essential property of human language, because if recursion doesn’t have to appear in one given language, then, in principle, it doesn’t have to appear in any language. This places them in the unenviable position of claiming that the unique property of human language does not actually have to be found in any human language.(!)

This, to be blunt, is where pure theory gets you. Bear in mind the subtitle of this book: ‘Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle.’ Life and language are inextricably interconnected.

The origin of human language is a mystery more beloved of amateur than professional linguisticians, for it is proving difficult to disentangle. Chomsky’s solution is that human beings, alone of all species, have in their minds a template prepared to receive and learn language. This is innate – genetic – presumably the result of a mutation which distinguishes humans from other animal species. In truth, it was not an unreasonable guess, in view of the astonishing speed with which human children develop a fully functioning version of the language of their linguistic community from an exposure to faulty and patchy input. Chomsky additionally posited a mental ability, unique to human infants, called the ‘Language Acquisition Device,’ – complementary to the Universal Grammar – also innate. It is true that children generally have an amazing facility for learning language until the age of about eight.

However, it is sixty years since the modern version of the Universal Grammar Theory was proposed, and in spite of the dedicated work of Chomsky himself and teams of loyal disciples, we are no nearer to finding it. At every moment of hope it recedes tantalisingly into the distance. Instead we find ourselves floundering in deeper and deeper levels of abstraction. Everett proposes instead that

There are other possible explanations, including logical requirements on communication, coupled with the nature of society and culture.

Looking closely at Pirahã, Everett noted that where it differed from ‘mainstream’ languages, such as in its rejection of recursion, this seemed to be associated with distinctive features of Hi’aiti’ihi culture. The most important of these is the tribe’s dedication to an ethos of living entirely in the present, what Everett calls the Principle of Immediacy of Experience. Their refusal to countenance statements which do not conform to this principle is responsible for a number of features of the language. For example, Pirahã will not say, ‘Bring me the nails that Dan bought.’ The sentence, ‘Dan bought the nails,’ cannot be embedded in Pirahã as a subordinate clause because it is not a declarative statement explicitly rooted in the immediate present. Indeed, Pirahã seems to eschew subordination altogether.

So the Hi’aiti’ihi will not say, ‘Bring me the nails that Dan bought,’ but rather, “Bring me the nails. Dan bought those nails,’ adding another, very brief sentence, showing that the nails they want are the ones that Dan bought: ‘They are the very nails.’ This shows that the Hi’aiti’ihi have the mental ability to think recursively, even though they don’t express recursion syntactically. Language is always able to do whatever its speakers want, no matter what problems or (apparent) deficiencies there are. And the Hi’aiti’ihi are no less intelligent than we are. Like us, they are human.

The Principle of Immediacy of Experience influences not only syntax but also morphology. A Pirahã verb, in addition to a huge range of suffixes showing various aspects of it, always has a final suffix indicating the manner in which it relates to the present: it has to show that the action of the verb is vouched for by personal observation, reliable hearsay, or logical deduction. For example, the sentence Xoioi hi páxai kaopápi-sai- (literally, “Xoioi a fish caught”) is incomplete without a suffix on the verb indicating its relationship with the present. The suffix áagahá is one such suffix: it indicates that I (who am here speaking) saw him catch the fish: Xoioi hi páxai kaopápisaiáagahá (Xoioi caught[authenticated-by-personal-observation] a fish.)

Everett argues that the Principle of Immediacy of Experience lurks behind all or most of the unusual features of Pirahã that he noted in his research – the lack of words for left or right (they go by which direction the river lies), of numbers, quantifiers, comparatives, perfect tenses and colour terms, and the exceptionally small number of kinship terms. This is largely because all these tend to involve generalisation, which is anathema to the Hi’aiti’ihi. Likewise Pirahã does not do double possessives (‘my mother’s brother’s canoe’) or double adjectives (‘a small brown dog’), conjunction (‘I fished and he watched’), or disjunction (‘either Bob will come or Bill will come’).

In the case of kinship terms, where Pirahã has only four or five, the rationale is simply that the Hi’aiti’ihi have terms only for the relatives that they know:

The kinship terms do not extend beyond the lifetime of any given speaker in their scope and are thus in principle witnessable—a grandparent can be seen in the normal Pirahã lifespan of forty-five years, but not a great-grandparent. Great- grandparents are seen, but they are not in everyone’s experience (every Pirahã sees at least someone’s grandparents, but not every Pirahã sees a great-grandparent), so the kinship system, to better mirror the average Pirahã’s experience, lacks terms for great-grandparents.

The lexicon is governed by the Hi’aiti’ihi world view: living in the present.

For all these reasons Everett proposes that

Language is a by-product of general properties of human cognition, rather than a special universal grammar, in conjunction with the constraints on communication that are common to evolved primates (such as the need for words to appear out of the mouth in a certain order, the need for units like words for things and events, and so on), and the overarching constraints of specific human cultures on the languages that evolve from them … We are left with a theory in which grammar—the mechanics of language—is much less important than the culture-based meanings and constraints on talking of each specific culture in the world.

In other words, rather than even begin to think about suggesting that the Hi’aiti’ihi are not fully human, we need to broaden our view of what humans are. Everett’s linguistic discoveries – accidentally made, and innocently described, initially – offer us a vision of humanity and humanity’s most striking attribute – language – that differs from the one that has prevailed over the past half-century. Rather than prescribe what human language must look like, linguistics needs to extricate itself from the dead end it has got itself into, and examine instead what human language actually looks like, in all its many manifestations.

As Everett remarks,

There is an obvious appeal to the notion that humans are special and that they are, at least in their minds, unfettered by the limitations that beset the rest of the animal kingdom. The French philosopher René Descartes, whom Chomsky popularized among linguists, believed that there is a separate mental, creative essence that distinguishes humans from animals.

Yet we now know that animals, and even plants, interact with other members of their species in a range of amazing ways. ‘Don’t Sleep’, while emphasising the importance of recognising the diversity within our species, also reminds us that our continuity with other species is essential to our self-understanding. While a certain amount of anthropocentricity is inevitable, and I’m not advocating giving mice the vote, we need to keep it to a minimum in the interest of being fully human.