by Ada Bronowski

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the breezy weightless of: ‘La vie ne vaut rien, rien, … rien ne vaut la vie’ (life is worth nothing, nothing, …nothing is worth life’, here). The song is finesse incarnate if that already is not too much of an oxymoron since finesse is anything but carnal. The rich assonances of the refrain where ‘rien’ (nothing) rimes with ‘tiens’ (I hold) and echoes with ‘seins’ (breasts) lift the contradiction, making the breasts abstract and life concrete. The second, flippancy, is the sand British humour was built on from Bertie Wooster to Black Adder (was, alas, as David Stubbs shows in his recent Different Times: A History of British Comedy, that flippant British humour is now dead after Boris Johnson chose to do politics rather than comedy). It is the lightness that transforms despair into melancholy, the weight of the world on one’s shoulders into elegance and panache.

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the breezy weightless of: ‘La vie ne vaut rien, rien, … rien ne vaut la vie’ (life is worth nothing, nothing, …nothing is worth life’, here). The song is finesse incarnate if that already is not too much of an oxymoron since finesse is anything but carnal. The rich assonances of the refrain where ‘rien’ (nothing) rimes with ‘tiens’ (I hold) and echoes with ‘seins’ (breasts) lift the contradiction, making the breasts abstract and life concrete. The second, flippancy, is the sand British humour was built on from Bertie Wooster to Black Adder (was, alas, as David Stubbs shows in his recent Different Times: A History of British Comedy, that flippant British humour is now dead after Boris Johnson chose to do politics rather than comedy). It is the lightness that transforms despair into melancholy, the weight of the world on one’s shoulders into elegance and panache.

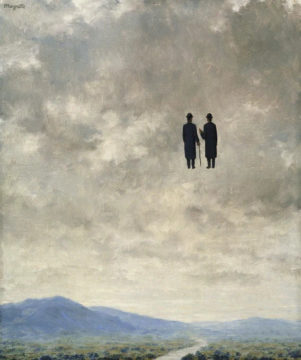

The third F is at the root of all lightness. Fantasy, etymologically, comes from the Greek word for light, phos – a word which already in antiquity contains the double-usage echoed in our English ‘lightness’: the shining light and what is detached from the heaviness of anchors. Fantasy is the realm of the light in all its senses. It is what the light shows us: surfaces, glimmers and shimmers which we can never quite be sure are true, nor can we positively dismiss as false. It is the realm of an in-between that we cannot not wish that it could be real.

Surely if we can see it, it must be real? Read more »

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written.

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written. Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club  1.

1. Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012.

Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012. How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us?

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us? I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

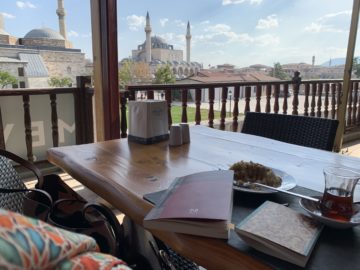

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.