by Tim Sommers

In honor of “Reading Hume Today,” a conference honoring professor Elizabeth Radcliffe and her work on Hume, here at my new home, the College of William and Mary, I thought I would read Hume today and revisit the topic of my very first 3 Quarks Daily article over five years ago, “Two Sources of Objectivity in Ethics.” (I also highly recommend Massimo Pigliucci’s essay responding to that piece.) However, if you just can’t wait to find out why Hume was in favor of gossip you can scroll down to the last few paragraphs.

What I want to talk about, and find endlessly interesting, is why David Hume, the fourth greatest philosopher of all time, thought morality must be subjective. Every time I return to it, I manage somehow to be surprised by his argument. In particular, what’s striking (to me) is that his argument is based on motivation. Morality must be subjective, he says, otherwise it couldn’t motivate us to action.

In Book II, Part III, Section III of his Treatise on Human Nature (subtitled, “Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects”), Hume sought to put an end “to talk of the combat of passion and reason.” “Reason is, and ought only be,” he famously proclaimed, “the slave of the passions”. He makes a number of striking claims in this section that epitomize this view. Perhaps, most shockingly he says, “It is not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.”

Here’s his line of reasoning, I think. (As befits the fourth greatest philosopher of all time there are many, many other readings of Hume.) Read more »

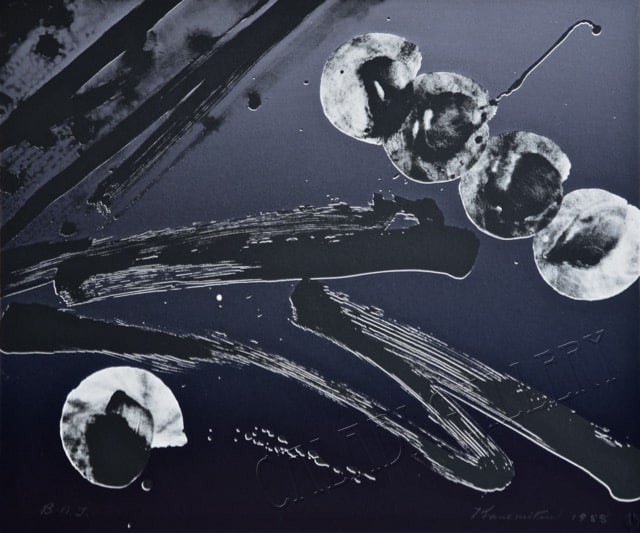

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988.

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988. “This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

“This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

In

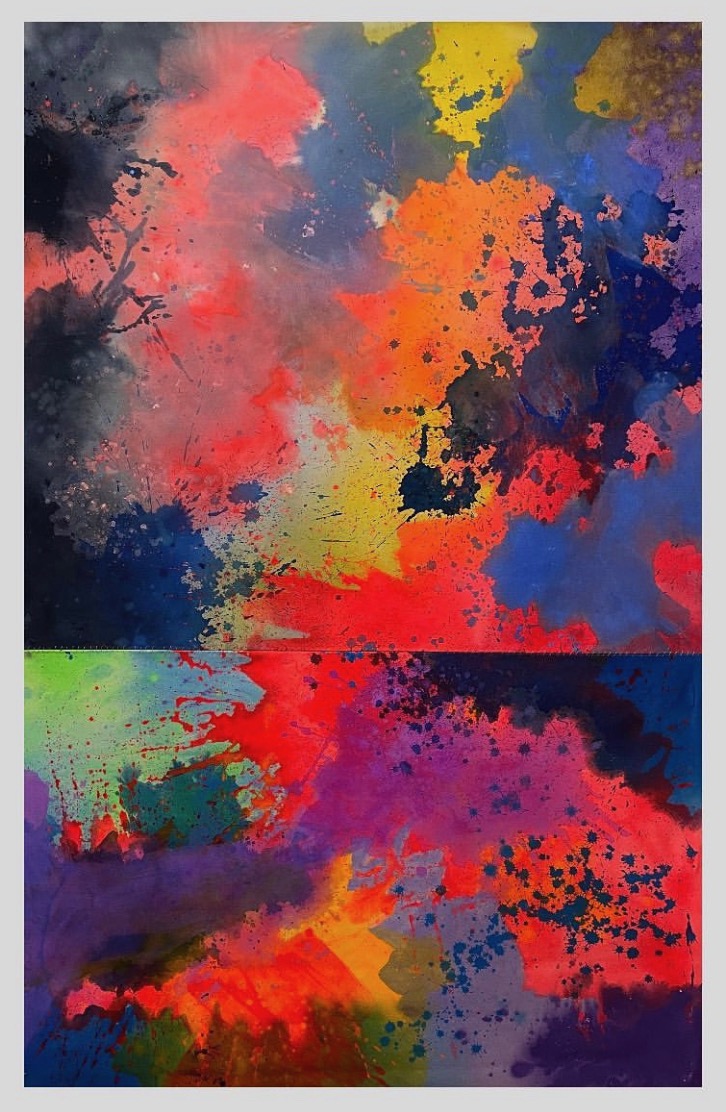

In  Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.

Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.