by Derek Neal

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16).

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16).

He spends the years of war attempting to escape boredom through painting, but his efforts are unsuccessful: “I felt that my pictures did not permit me to express myself, in other words to deceive myself into imagining that I had some contact with external things—in a word, they did not prevent me from being bored (23). The boredom that the narrator describes is not simply a lack of interest in an activity, but something deeper, more akin to meaningless, existential despair, or Camus’ idea of the absurd. His boredom is what we might call ennui in English (the French word for boredom), which seems to indicate a more profound weariness and listlessness than ordinary boredom.

Time moves slowly when one is bored, and one would like to find a way to speed it up. The narrator, Dino, says that painting is “as good a way of passing the time as any other” (16). His mother, talking about a book she’s reading but whose author she can’t remember, says “What matters to me is to pass the time, more than anything else. One author or another, it’s all the same to me” (55). Reading, for Dino’s mother, provides a cure for boredom because she does not feel that her life is meaningless, whereas Dino’s painting is unable to provide the meaning his life lacks. Time passes for her but not for him. Read more »

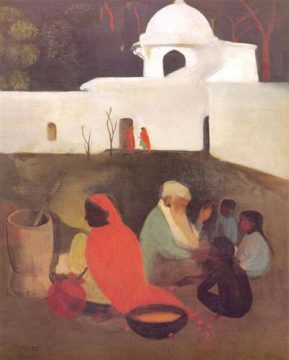

The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.

The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.

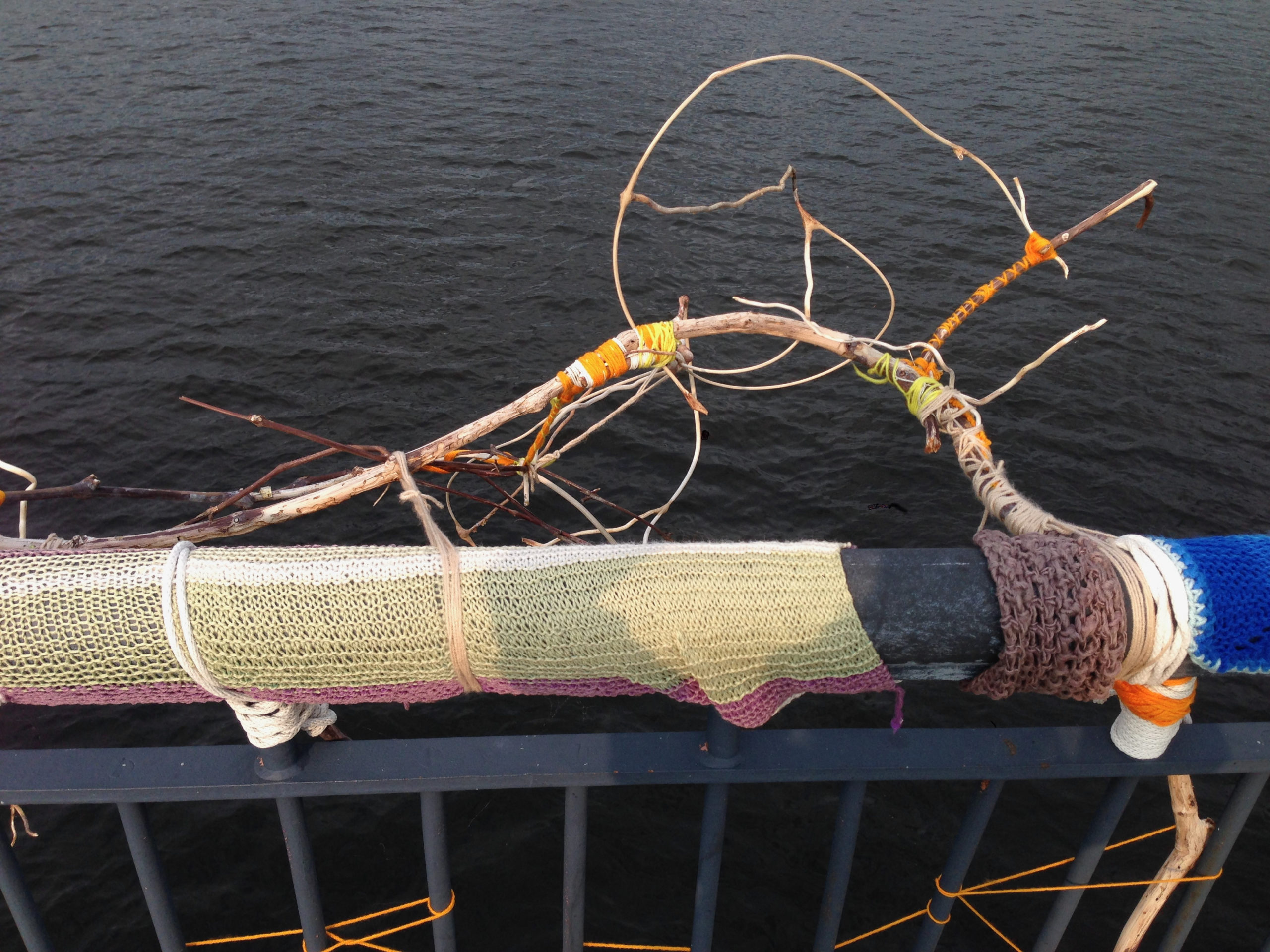

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Daniel Goleman’s

Daniel Goleman’s

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.