by Jochen Szangolies

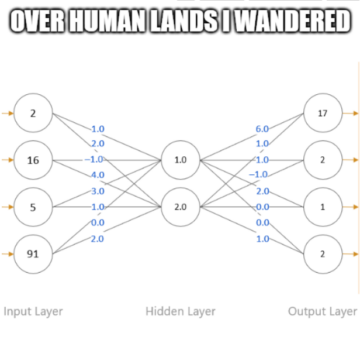

There is a widespread feeling that the introduction of the transformer, the technology at the heart of Large Language Models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s various GPT-instances, Meta’s LLaMA or Google’s Gemini, will have a revolutionary impact on our lives not seen since the introduction of the World Wide Web. Transformers may change the way we work (and the kind of work we do), create, and even interact with one another—with each of these coming with visions ranging from the utopian to the apocalyptic.

On the one hand, we might soon outsource large swaths of boring, routine tasks—summarizing large, dry technical documents, writing and checking code for routine tasks. On the other, we might find ourselves out of a job altogether, particularly if that job is mainly focused on text production. Image creation engines allow instantaneous production of increasingly high quality illustrations from a simple description, but plagiarize and threaten the livelihood of artists, designers, and illustrators. Routine interpersonal tasks, such as making appointments or booking travel, might be assigned to virtual assistants, while human interaction gets lost in a mire of unhelpful service chatbots, fake online accounts, and manufactured stories and images.

But besides their social impact, LLMs also represent a unique development that make them highly interesting from a philosophical point of view: for the first time, we have a technology capable of reproducing many feats usually linked to human mental capacities—text production at near-human level, the creation of images or pieces of music, even logical and mathematical reasoning to a certain extent. However, so far, LLMs have mainly served as objects of philosophical inquiry, most notable along the lines of ‘Are they sentient?’ (I don’t think so) and ‘Will they kill us all?’. Here, I want to explore whether, besides being the object of philosophical questions, they also might be able to supply—or suggest—some answers: whether philosophers could use LLMs to elucidate their own field of study.

LLMs are, to many of their uses, what a plane is to flying: the plane achieves the same end as the bird, but by different means. Hence, it provides a testbed for certain assumptions about flight, perhaps bearing them out or refuting them by example. Read more »

Latifa Echakhch. Taqsim, 2017.

Latifa Echakhch. Taqsim, 2017.

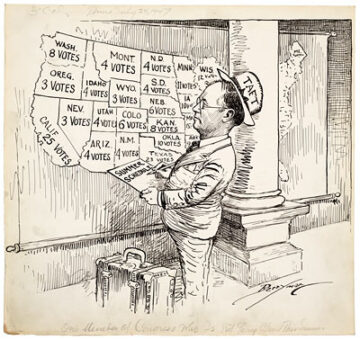

In 2015, political scientist Larry Diamond warned against defeatism in the face of what he called the

In 2015, political scientist Larry Diamond warned against defeatism in the face of what he called the

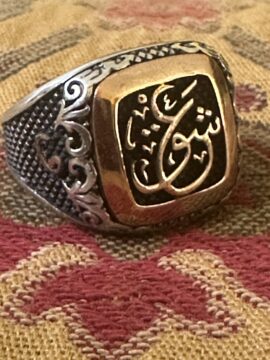

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit.

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit. Christine Ay Tjoe. First Type of Stairs, 2010.

Christine Ay Tjoe. First Type of Stairs, 2010. Two spaces after a period, not one. If a topic sentence leading to a paragraph can get a whole new line and an indentation, then other new sentences can get an extra space. Don’t smush sentences together like puppies in a cardboard box at a WalMart parking lot. Let them breathe. Show them some affection. Teach them to shit outside.

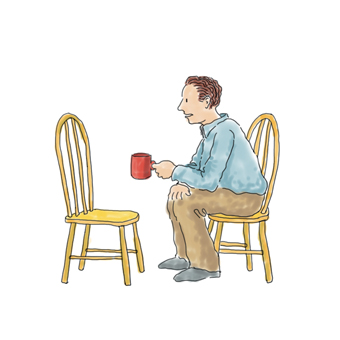

Two spaces after a period, not one. If a topic sentence leading to a paragraph can get a whole new line and an indentation, then other new sentences can get an extra space. Don’t smush sentences together like puppies in a cardboard box at a WalMart parking lot. Let them breathe. Show them some affection. Teach them to shit outside. Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of

Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).