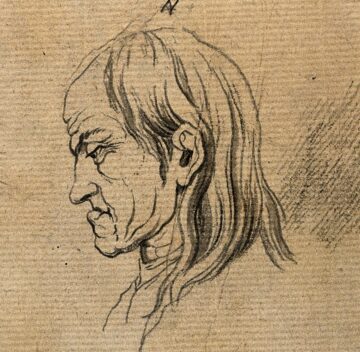

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

If Harold Bloom is correct in asserting that, in some sense, Shakespeare invented the human, not in the sense that Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, Alexander Graham Bell the telephone, Thomas Edison the light bulb, Hedy Lamar got a patent for frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology, not to mention Yahweh’s work on Adam and Eve, but in the modest sense that he bequeathed us a deeper understanding of ourselves through giving voice to aspects of human behavior that had hitherto gone unremarked. Bloom singles out Hamlet for special consideration, arguing that he is perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest gift – though Falstaff is in the running. Hamlet has come down to us as the melancholy Dane. Accordingly, let us conjecture that modern man was born in melancholy.

A few years later Robert Burton would publish The Anatomy of Melancholy. It was a smash hit and went through five more editions during Burton’s life. It made Burton’s printer a fortune. While the book is indeed about melancholy, it is also about damned near everything else under the sun. It was subsequently parodied in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, no mean feat as the original has something of a parodic character unto itself.

Here is how Burton defined melancholy:

Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or habit. In disposition, is that transitory melancholy which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causeth anguish, dullness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, any ways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing frowardness in us, or a dislike. In which equivocal and improper sense, we call him melancholy that is dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill disposed, solitary, any way moved, or displeased. And from these melancholy dispositions, no man living is free, no stoic, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine, that can vindicate himself; so well composed, but more or less, some time or other he feels the smart of it. Melancholy in this sense is the character of mortality.

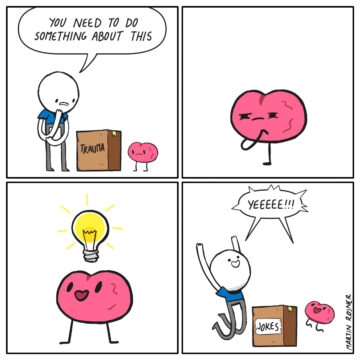

To live is to know melancholy. We post-moderns are more likely to call it depression.

That’s what this post is about, depression, but also growth. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.