by Barry Goldman

Because I serve as an arbitrator for FINRA, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, I have a Disclosure Report posted on the FINRA website. That 11-page document shows my employment history, education and training, and it lists every place I’ve had an investment account, every agency where I’ve served as an arbitrator, every professional organization I belong to, and it provides a link to each of my FINRA decisions.

Parties who have cases with FINRA can review that report when they are selecting their arbitration panel. If I am selected to serve on a panel, I am required to complete a more case-specific Arbitrator Disclosure Checklist. That 14-page document requires me to disclose:

- any direct or indirect financial or personal interest in the outcome of the arbitration;

- any existing or past financial, business, professional, family, social, or other relationships or circumstances with any party, any party’s representative, or anyone who the arbitrator is told may be a witness in the proceeding, that are likely to affect impartiality or might reasonably create an appearance of partiality or bias;

- any such relationship or circumstances involving members of the arbitrator’s family or the arbitrator’s current employers, partners, or business associates; and

- any existing or past service as a mediator for any of the parties in the case for which the arbitrator was selected.

There’s more. The duty to disclose is ongoing. We could be four days into a hearing when a witness appears who I recognize from a previous case. I have a duty to disclose that fact when it occurs. FINRA arbitrators are required to complete training programs periodically, and the organization produces several publications. The thrust of those training programs and many of the publications is the importance of disclosure. The rule is to disclose anything that may appear to present a conflict of interest. The threshold is low: if the potential for the appearance of a conflict occurs to us, we are required to disclose it.

There are two reasons for this. Read more »

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it.

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it. A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

When I started as a Monday columnist at 3 Quarks Daily in July of last year, my debut

When I started as a Monday columnist at 3 Quarks Daily in July of last year, my debut

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

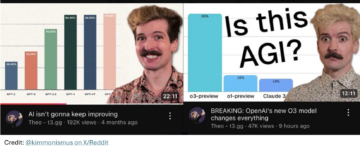

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen