by Adele A. Wilby

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

The Australian author Richard Flanagan is the 2024 winner of the prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction for his book Question 7. The book is a brilliant weaving together of memory, history, of fact and fiction, love and death around the theme of interconnectedness of events that constitute his life. Disparate connections between his father’s experience as a prisoner of war, the author H.G. Wells, and the atomic bomb all contributed towards making Flanagan the thinker and writer he is today. The book reveals to us his humanity, his love of family and of his home island of Tasmania; it is what Flanagan expects of a book when he says, ‘the words of a book are never the book, the soul is everything’, and this book has ‘soul’.

The book opens with Flanagan visiting the site of Ohama Camp where his father was interned as a slave labourer in the undersea coal mines in Japan during World War II. There is ‘no memorial, no sign, no evidence’ of the camp or the suffering that existed on that spot; all that remains is a ‘love hotel’, but his visit to this site establishes the first link in a chain of interconnected events in his life.

Flanagan’s father never expected to survive the cruelty of the guards and the grinding work as a slave labourer in the coal mines, yet faraway in Europe, unbeknown to him, scientific minds were actively working on the idea of a bomb with extraordinary lethal potential, a bomb that would save his life and have a profound impact on the future of humanity and shape world events. The Japanese city of Hiroshima became the experimental testing ground for this atomic bomb and tens of thousands of ‘unknown souls’ perished, ‘vaporised’, by the force of the energy of such a lethal weapon. The atomic bomb brought the war to an end, saved Flanagan’s father’s life and ultimately brought Flanagan himself into existence. Read more »

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we

After I moved from the UK to the US it took me only a couple of years to cede to my friends’ pleas and start driving on the right. When in Rome, and all that. But I still like to irritate Americans by maintaining that we Brits are better at this essential mechanical skill. I mean, when we drive, we  Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

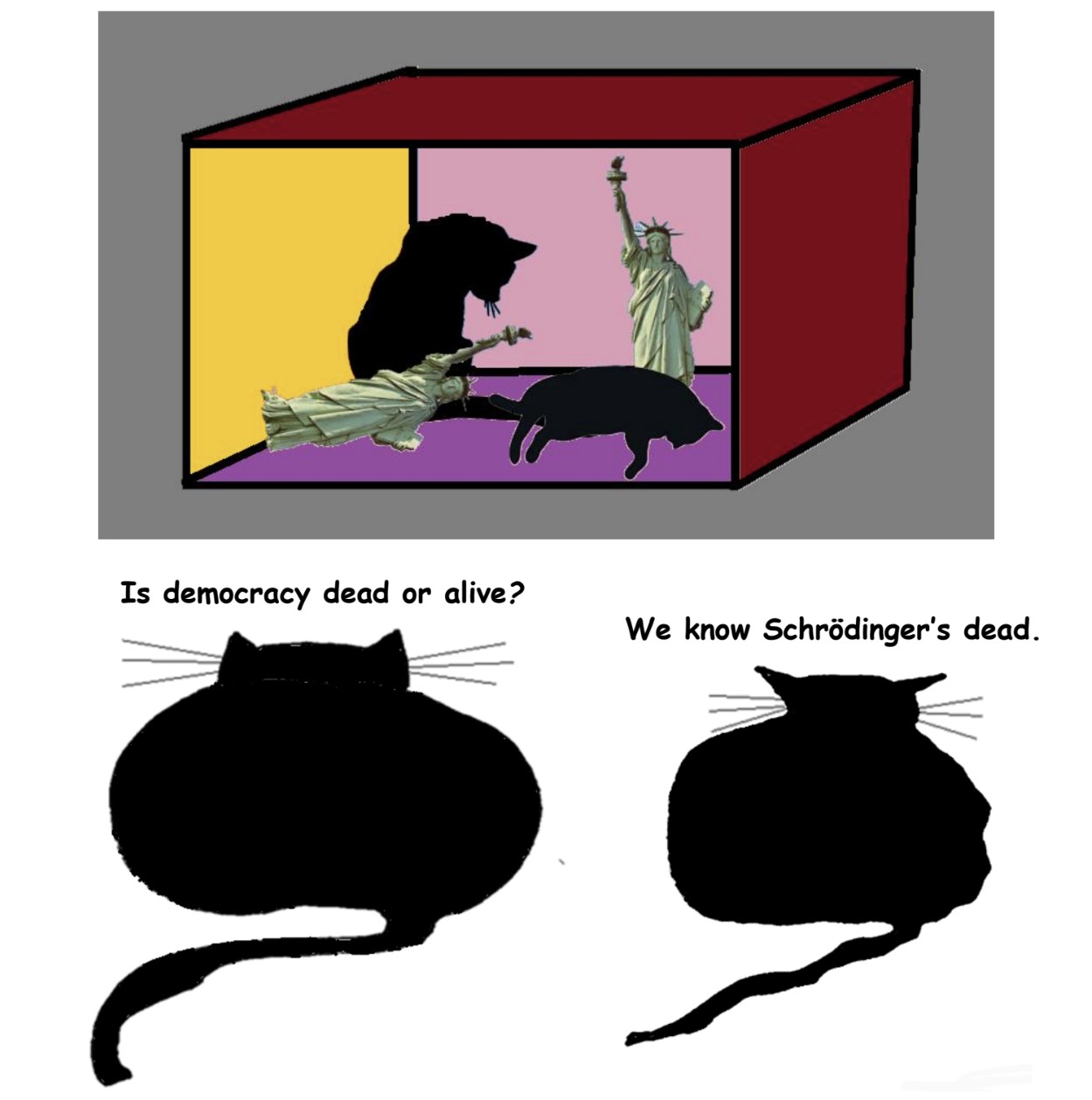

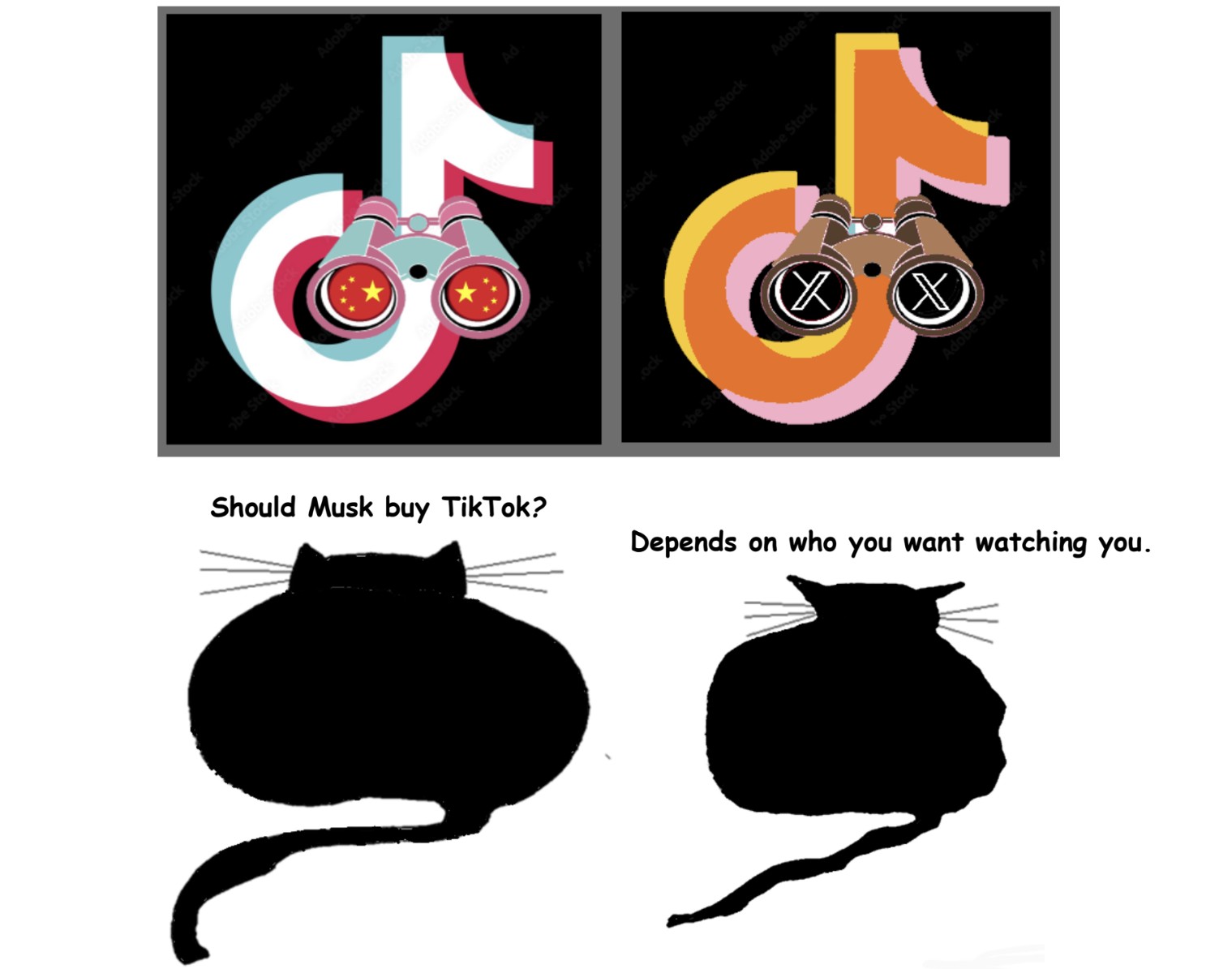

Sughra Raza. Ephemeral Apartment Art. Boston January 4, 2025.

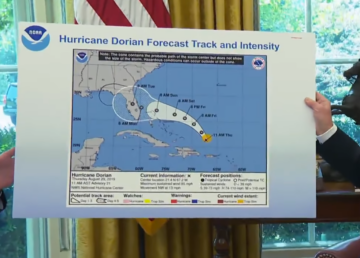

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

The same media that warned us against Donald Trump now warn us against tuning out. Though our side has lost, we must now ‘remain engaged’ with the minutiae of Mike Johnson’s majority

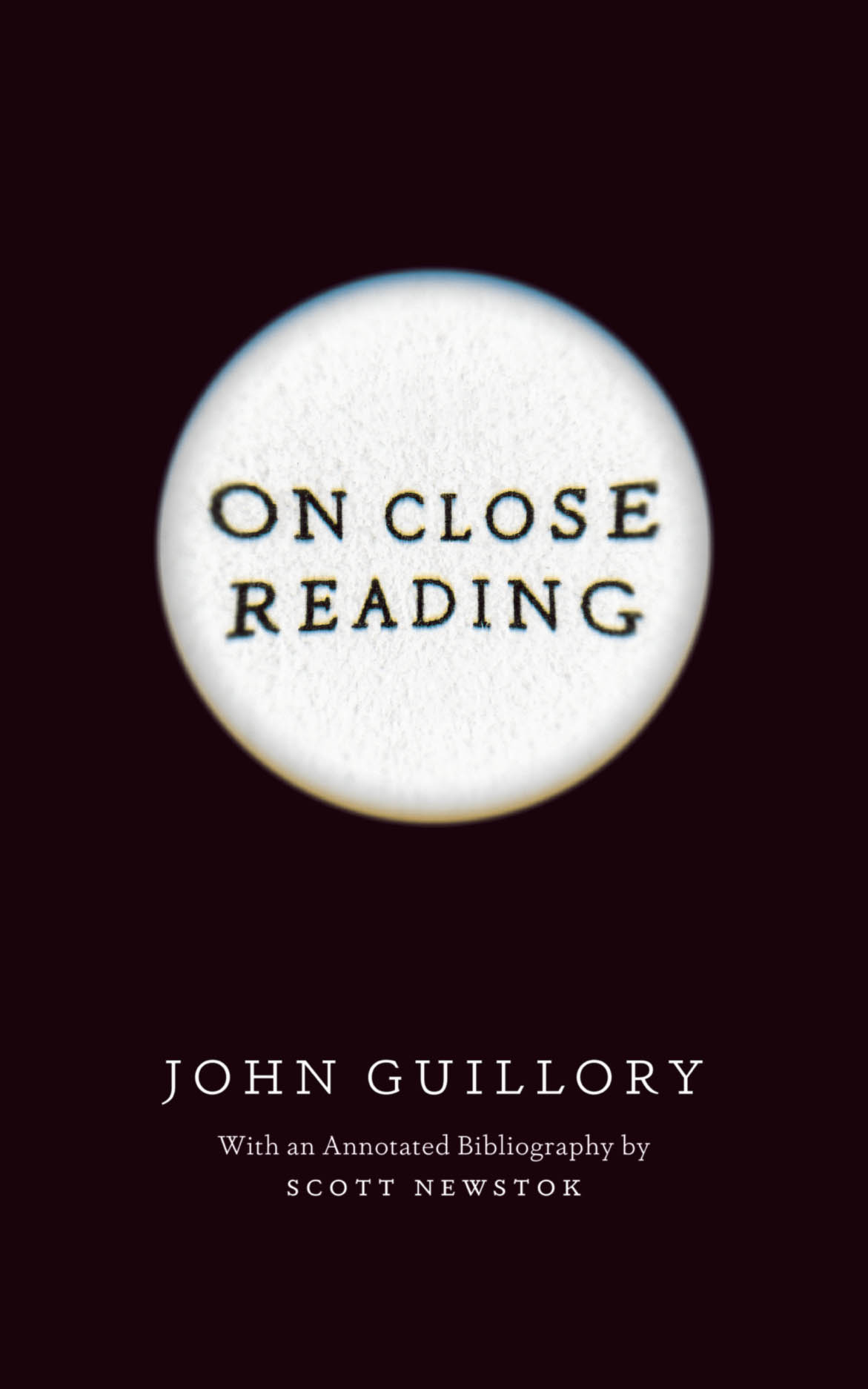

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it.

What do swimming, running, bicycling, dancing, pole jumping, tying shoelaces, and reading all have in common? According to John Guillory’s new book On Close Reading, they are all cultural techniques; in other words, skills or arts involving the use of the body that are widespread throughout a society and can be improved through practice. The inclusion of reading (and perhaps, tying shoelaces) may come as a surprise, but it is Guillory’s goal in this slim volume to convince us that reading, and in particular, the practice of “close reading,” is a technique just like the others he mentions. This is his explanation for the questions he explores throughout the book—namely, why the practice of “close reading” has resisted precise definition, and why the term itself was so seldom used by the New Critics, the group of theorists most associated with it. A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

When I started as a Monday columnist at 3 Quarks Daily in July of last year, my debut

When I started as a Monday columnist at 3 Quarks Daily in July of last year, my debut