Plastic rose among a pile of assorted trash at the side of a road in Brixen, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Plastic rose among a pile of assorted trash at the side of a road in Brixen, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Akim Reinhardt

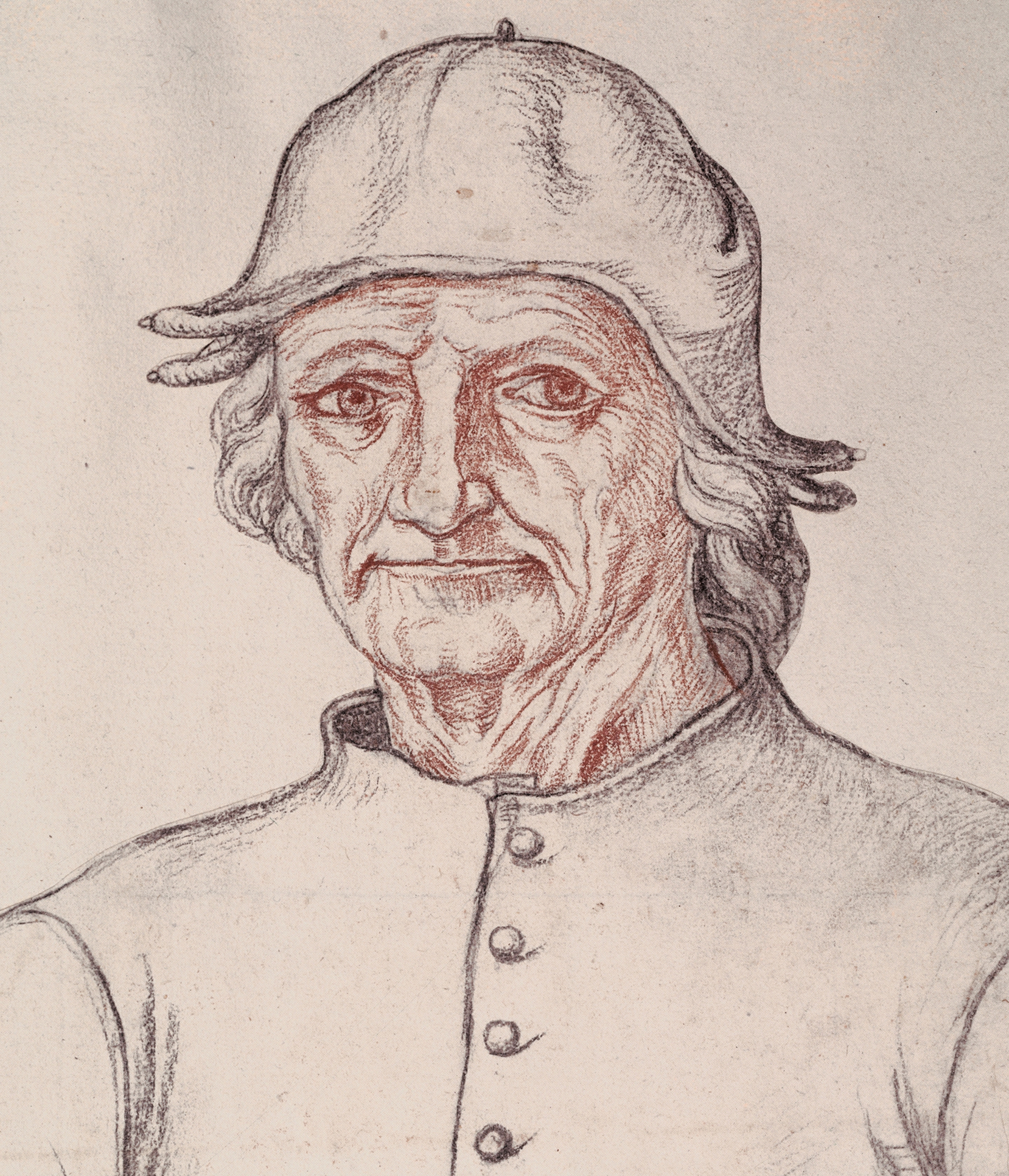

Medieval historians hate it, don’tcha know, when people talk about the Dark Ages. Scholars haven’t used the term in decades, eschewing it as an unfair and inaccurate description of 500–1000 years of European history, give or take. The Middle Ages weren’t just filth, poverty, violence, and ignorance, historians protest. They were actually a series of eras that featured the development of many knowledges and cultural innovations!

As someone who studies and teaches Native American history, I’m like: Hold my beer. You wanna talk about historical misperceptions unfairly miscasting regions and peoples as backwards, impoverished, and violent? You can’t even imagine. The Indigenous Americas featured numerous wealthy, art-laden empires. Large, orderly, planned Indigenous cities made even early modern European cities seem the filthy, disease-ridden, shambolic wreck by comparison. And all of it erased from popular historical memory so that in the aftermath of violent invasion, the colonial consciousness can be eased with lies about primitive savages.

But whether histories are erased and ignored, like those of Indigenous empires, or studied to the point of saturation, like much of European history, the truth is we can only imagine the past. We can never relive it. Even if it is recent and filmed, we can never be there, we can never participate. And even if we were there, even if we did participate and remember, memories aren’t as real as we think; they are reconstructions. Not merely subjective, memories are also limited and faulty.

And thus, the past always has at least one thing in common with the future. It must be imagined.

Was this time and place a dark age? Is a dark age coming? Look forward or back, we cannot know for sure. And anyway, what do we mean by “dark age.” Perhaps something about pervasive ignorance, the corruption of truth, and great difficulties in overcoming fallacies? Read more »

by Marie Snyder

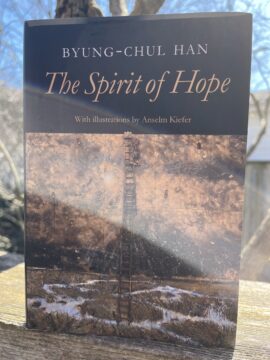

Byung-Chul Han’s The Spirit of Hope is a beautiful book, the kind you want to treat with care and won’t dare dog-ear a page. Anselm Kiefer’s illustrations throughout provide a place for contemplative moments between ideas. It’s more immediately accessible than The Burnout Society, which took me weeks to wrap my head around, yet no less profound.

We like a secure illusion of control over the world, yet that hasn’t gotten us much further along. We recognize something’s missing. Han writes, “Amid problem-solving and crisis management, life withers. It becomes survival. … It is hope that opens up a meaningful horizon” (2).

Han explains how a lack of hope furthers the current neoliberal capitalist trajectory:

“Fear and resentment drive people into the arms of the right-wing populists. They breed hate. Solidarity, friendliness and empathy are eroded. … Democracy flourishes only in an atmosphere of reconciliation and dialogue. … Hope provides meaning and orientation. Fear, by contrast, stops us in our tracks. … Hope is eloquent. It narrates. Fear, by contrast, is incapable of speech, incapable of narration” (2-3).

Climate activist Roger Hallam recently wrote that the human race is likely going extinct this century, yet he demonstrates his hope in the very action of continuing to write our way through and by suggesting public alternatives to political capture. When we’re no longer open to seeing possibilities, we get held fast by fear, but it appears to be a feature of the system, not a bug.

“The current omnipresent fear is not really the effect of an ongoing catastrophe. … The neoliberal regime is a regime of fear. It isolates people by making them entrepreneurs of themselves. … Our relation to ourselves is also increasingly dominated by fear: fear of failing; fear of not living up to one’s own expectations; fear of not keeping up with the rest, or fear of being left behind. The ubiquity of fear is good for productivity. … To be free means to be free of compulsion. In the neo-liberal regime, however, freedom produces compulsion. These forms of compulsion are not external; they come from within. The compulsion to perform and the compulsion to optimize oneself are compulsions of freedom. Freedom and compulsion become one. … We optimize ourselves, exploit ourselves, to the bitter end, while harbouring the illusion that we are realizing ourselves. These inner compulsions intensify fear, and ultimately make us depressive. Self-creation is a form of self-exploitation that serves the purpose of increasing productivity” (9-10).

This brings to mind the many life hacks promoted to help self-automate our lives by creating habits to try to help us blow through chores and work without noticing it, as if to better sleepwalk through it all in a psychological version of Severance. As long as we’re optimizing ourselves, we’re not being; we’re merely objects that can work more efficiently, which further prevents our connection with others. Social media also paradoxically erodes social coherence, but “Hope is a counter-figure, even a counter-mood, to fear: rather than isolating us, it unites and forms communities” (10-11). Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner — the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern. —André Breton

It’s 1923. And a student grabs a book off a shelf. Running for his life, book held tight, he is just one step ahead of a massive earthquake that would shake the world for four long minutes. Out of the building, he joins the surging crowds on the streets of Tokyo. People are in deep shock, but the young man is calm, reading as he walks among them. The book he grabbed was a novel by William Morris called News from Nowhere. It’s a work of socialist utopianism.

According to Shuzo Takiguchi, who is considered to be one of Japan’s great surrealistic poets, this experience was the start of his life as a poet. Disaster as the start of things. But despite what he claimed, we know that he’d already turned away from medicine, which his parents so desperately hoped he would study, instead spending more and more time in the university library reading literature.

And so, the Great Kanto Earthquake was not so much the inciting incident, as the event that let him off the hook.

As soon as the trains were running again, he returned to his family home in the countryside, where he tried to become a teacher. When this didn’t work, he was persuaded to return to university in 1925, and that was when he met the poet and classics scholar Junzaburō Nishiwaki, who was well-known at university for having studied at Oxford. Together with a group of other poets, they founded a literary journal devoted to French surrealism, which by that time had become Japan’s most popular avant-garde movement. Read more »

by Eric Feigenbaum

In 1965, Singapore’s Founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew corrected an Australian news reporter:

“I am not in fact Chinese. I am Malaysian. I am by race Chinese. I am no more Chinese than you are an Englishman.” He refined the example on other occasions, eventually saying he was “no more Chinese than President Kennedy was an Irishman”.

Like his examples, Lee grew up speaking English – it was a first language for him along with Malay.

In those days, it was far from clear English would continue as a dominant language in the countries spun out of British Malaya, let alone that it would later create an unexpected cascade of successes for Singapore.

One of the pressing issues of Singapore’s early days was the cultural tension related to choosing the fledgling country’s language. The 500 square kilometer island was nearly empty when the British claimed it in the 1820’s, turning it into an open-port city with a very loose immigration policy. When considering the issue in 1965, few if any imagined their choice of language could become an economic asset of untold dimensions.

Even prior to Singapore’s inception, the question of a national language among the major three ethnicities – Chinese, Malay and Tamil Indian – was charged. It highlighted just how much Singapore was a land of immigrants – migrants really – who left their home countries in search of work and opportunity. There was no “Singaporean” ethnicity – just a collection of people who called Singapore home.

Much agonizing led to the Singaporean version of the Connecticut Compromise. Singapore would make Mandarin, Malay, Tamil and English all official, legal languages that could be used in court or on legal documents. Yet it would also make English – the language of no one ethnicity – the working and educational language of Singapore. One common tongue everyone could share. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self portrait with Shutter and Tree, Merida, March 2025.

Sughra Raza. Self portrait with Shutter and Tree, Merida, March 2025.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Michael Liss

It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens. —Aristotle, Politics

Aristotle was an optimist. Try to visualize an old Greek guy in a himation as a talking head on one of the Sunday shows. He’s never getting an invite to the White House—and it’s not just because of the clothes. Limits on an American President? This American President?

It is grim out there if you are a Democrat. The House, gone; Senate, gone; White House, so far away the distance is measured in light years. SCOTUS, nauseatingly gone. Day after day, Trump, with the cunning of an outlaw biker President, uses his power to taunt, punish and utterly dominate anyone who had or has the temerity to oppose him. Based on the number of prominent people and institutions that have knelt before him, he’s darn good at it. He’s also darn good at speaking to his supporters, and particularly skilled at keeping his fellow Republicans in line. Trump speaks fluent Trump, and Republicans, increasingly, are learning repeatable, debate-ready whole paragraphs of Trumpiness to be used in almost any circumstance. It’s a “Newspeak” modernized from 1984, and it works. People understand it. They react to it viscerally.

How about Democrats? With some notable exceptions, they mostly speak Esperanto. Excellent at cocktail parties with your photos of the Prado (“The Goyas were amazing!”), but not all that useful for everyday conversation.

Full stop. I am not going on an extended “TDS” rant, or its post-November 2024 variant of perpetual Democratic self-flagellation. Newspeak is also a definite no. Let’s talk about power in our system, the extent and implications of it, how it’s expressed and constrained, and the political application of it. In short, let’s channel our inner Aristotle and survey the role of the Rule of Law in contemporary politics.

Perhaps it is best to state the obvious at the beginning: What role? The Rule of Law is a losing argument in recent elections—and it is a losing argument to make to politicians. Maybe that will change, maybe it’s a temporary phenomenon of the Trump Era, maybe it just lacks a compelling spokesperson, but many voters don’t care—and in fact, some cheer its failure.

What is it they are rejecting? What is the Rule of Law? Read more »

by R. Passov

There’s a small, interesting book store in NYC, small enough for a pixie-of-a-lady and about 200, mostly rare, mostly old, and almost exclusively, cookbooks. The store is near my favorite bar and that’s all I’m going to say.

I first wandered into that shop while trying to walk off a handful of afternoon beers (at that favorite bar). I’ve since gone back many times, usually in search of quirky presents such as a picture book, made in the late 1970’s that contains a replica of every label for every bottle of Italian wine that had been offered in the prior one hundred years – exactly what to get an Italian friend who makes his own pasta and wine. For another close friend I procured a first edition of Diet and Reform by M K Gahndi, perfectly fitting in my view as I had come to believe that close friend was in need of both.

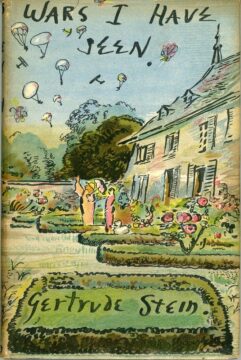

But this essay is not about that bookstore or the nearby bar nor the books in that store that I have found for others. This essay is about a rambling discourse, written as WWII approached its last summer, written mostly in Culoz, France, a small town much closer to Switzerland than to Paris, where Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas spent the last years of WWII.

Stein’s book, Wars I have Seen, is a repetitive reflection on living in the foothills during the waining days of the war. The French were emerging from one regret – that of having lived meekly under the dominion of the Germans – into another. They had allowed for their own subjugation by such a meek foe, as though the shame was not in having been conquered but rather that the conquerors turned out not to be all that.

I knew nothing about Wars I Have Seen. What caught my attention was first its cover – a distinctive jacket design by Cecil Beaton – and next that, unlike almost all other books in that shop, it was not a cookbook. Read more »

I sometimes shudder at old pics,

their bittersweetness, their

cutting edge, their tricks:

….. daughter’s brilliant smiles,

….. mittens hung from cuffs,

….. Kodachrome taunts of time

….. —enough

I’d rather mine old stones, turn up

what’s scattered within my heart and head

….. —the gold

I’d rather stick with what’s been deeply sown,

take joy in what, within my heart, has grown.

I do not like as much, nostalgic risks.

The photo box stays beneath the bed

with CDs and snaps of bygone’s code

on paper, or on disks.

….. When memory goes will it matter?

Then, I may not even recognize the

aliens who peer from three by fours

or smile from screens in pixel splatters.

Love is as it comes in time, as it is in

moments real. Now is breath’s agency.

Now is never still, but alive, not held

in poignant frozen shots—

….. is immediate

….. is not mere blur

….. is true

….. sublime

Jim Culleny

Jan 29, 2011_Rev_032125

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by David Greer

Countries love their symbols. But what do those symbols tell us?

One of President Biden’s final actions before handing over the keys to the White House was to sign into law a unanimous bipartisan bill, perhaps one of the last of those for a good long time, declaring the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) the national bird of the United States of America.

Cue media yawn. December 2024 was too replete with Trumpian outrage (for and against) to notice. Besides, hadn’t the eagle as national symbol been settled a couple of hundred years ago?

Actually, more like 250 years ago, when the Continental Congress, having loosed the chains of empire, decided in 1782 to insert the image of a bald eagle on the Great Seal of the United States. On it, the eagle clutches an olive branch in one talon, a sheaf of arrows in the other – prepared for peace or war as circumstances require. The bald eagle must have seemed an obvious pick as a national symbol, the epitome of strength and independence and native to every state in the union. Generations of Americans grew up assuming the bald eagle was their national bird, but that status didn’t become official until the 2024 bill, introduced by Amy Kobuchar, sailed through both the Senate and House and landed on the president’s desk. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

Wine tasting occupies a curious, liminal space in the architecture of human experience. It is sensual yet intellectual, visceral yet highly codified, personal yet somewhat anxiously public. It is therefore persistently haunted by the question of whether it can legitimately aspire to objectivity or is it hopelessly mired in personal preference and cultural contingency.

Most discussions of this topic settle into the familiar but facile polarity between the subjectivists, who proclaim that all tasting is little more than the projection of our private whims onto liquid canvases, and the objectivists, who dream of a science of wine, a rigorous catalog of chemical facts from which flavor profiles might be derived like astronomical coordinates. Both camps miss what makes wine worth talking about in the first place: the irreducible relational character of taste.

The notion of objectivity, as it was forged in the smithy of modern science, is a curious thing. It assumes the world is composed only of discrete entities endowed with properties that exist independently of how they are observed. This account of objectivity works reasonably well when applied to the movement of planets or an analysis of the chemical constituents of wine but falters with phenomena whose existence depends on being perceived. The taste or smell of a wine is not given in isolation but unfolds as an interplay between the liquid, our sensory mechanisms, and the mind. Read more »

by Christopher Hall

“In 2025, during an event to celebrate the inauguration of Donald Trump for his second term, the richest man in the world gave a Nazi salute to the crowd.” This is a sentence which, circa 2005, would have made for a rather overblown introduction for a YA dystopian novel. But here we are, and it did happen. It did happen – right? No, calling this a Nazi salute was leftist cancel culture in action. No, Elon is just very socially awkward and/or autistic. No, even the Anti-Defamation League says it wasn’t a Nazi salute. In many corners of the media, the message was simple: don’t believe your lying eyes.

What is inescapable is the sense of the ludicrous – you either think it’s ludicrous that we’re debating at all what was clearly a fascist gesture, or that there are people who think so, because it clearly wasn’t. The interpretational gambits being played here are both nettlesome and exhausting. And it isn’t solved by simply dismissing Musk as a troll. The strange loop of trolling, where we’re moving forward but we somehow end up at the beginning, usually involves the question of intention, always daring you to think both that he really means it and that it’s all a joke. And so maybe Musk’s gesture was innocent and maybe it wasn’t – but that’s all part of the troll. How can you take such a thing so seriously? (How can you not?) An arm raised at roughly a 45 degree angle – that’s what upsets you? (It’s literal Nazism, so of course it does!) But his hand was raised at a slightly higher angle – isn’t that just a wave? (Oh, stop bothering me and go read your Trump Bible.) It may be that Kekistan is long past its expiration date (the half-life of memes being pretty short), but the spirit remains intact and present. Trolling is a language game, and you lose if you react to it at all.

Trolling is also, as is frequently said, an art, and as perverse as it may sound, I want to look for a moment at The Gesture as a work of performance art. Read more »

by Nils Peterson

Today (June 13) is W.B. Yeats’s birthday. He would have been 157. I am compelled to remark upon the similarities between Yeats, the Nobel prize winner, and Peterson, the scribbler in the corner. I quote from a short Yeats biography, “he was lackluster at school,” an elementary report card said he was “Very poor in spelling,” and his early poems were described as a “vast murmurous gloom of dreams.” Peterson’s academic career and early poems could be described in a similar fashion. Where they differ is noted in that Yeats’s elementary report, “Perhaps better in Latin than in any other subject.” Peterson says of himself that the “D” he received in Latin was not earned, but a gift.

Yeats said of the woman he loved that she affected him as “a sound as of a Burmese gong, an over-powering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes.” Peterson says that that’s got it about right, “an over-powering tumult…[with] many pleasant secondary notes,” but adds “There are ‘dis-chords’ too. Music that is too sweet for too long gets tedious. One needs notes that grind against each other as well as those that get along.”

Yeats wrote that “Bodily decrepitude is wisdom.” Peterson is testing out that hypothesis. He’s not yet convinced. Yeats says, “This is no country for old men….” Peterson wonders if there is such a place, not wanting to end up as Yeats seems to as a mechanical cuckoo hanging in a cage in the emperor’s palace. Yeats thought of himself as kind of a jester, Peterson thinks himself as more of a clown. Both are useful, though the jester is more likely to get the Nobel prize.

Yeats, towards the end of his life after a dry period, wondered what the source of his poetry was and found it in “the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart where the “old kettles, old bones, old rags” of his life lived along with “that raving slut/Who keeps the till.” He thought he “must go lie down there again” amidst the objects of his life to be refreshed. Peterson finds himself “Down in the Dumps” where he “sits on a bucket feeling/ supple as a seal” and bangs on “a bottle with his lost wooden horse leg, chinka chink-a chinkety-chaw-chaw-chaaah!” Read more »

by Priya Malhotra

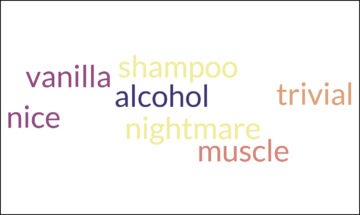

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

Language is a traveler. Words cross borders, crisscross centuries, and sometimes transform so completely that their meaning is completely altered. A term that once conveyed insult might, centuries later, become a compliment. A spice that once evoked luxury may later come to symbolize the ordinary. A simple verb in one language may be borrowed and reshaped into something spectacular in another.

The English language, restless and ever-expanding, is a patchwork of borrowed words, forgotten histories, and surprising transformations. While the English language’s primary roots lie in Old English, Old Norse, Latin, and French, it has also incorporated words from languages such as Arabic, Hindi, Dutch, Italian, and Japanese. Some words have arrived quietly, slipping into common speech without much notice. Others are shaped by conquest, trade, or scientific discovery. But every word has a journey—a story hidden beneath its surface, waiting to be uncovered.

Here are seven words whose unexpected and dramatic voyages through time and place remind us that language is not something static – it’s always moving and always changing.

For a word that now suggests something bland, colorless, and ineffectual, nice has had quite the rip-roaring journey. It started off as an insult. Originating from the Latin word nescius meaning “ignorant” or “unaware,” it entered Old French as nice, as in “careless” or “clumsy.” By the late 13th century, Middle English adopted nice to describe someone as “foolish” or “senseless.”

Over the subsequent centuries, nice experienced a series of dramatic shifts in meaning. In the 14th century, it conveyed the sense of being “wanton” or “lascivious,” a far cry from its modern use. By the 15th century, it had transformed again, then used to describe someone who was “fastidious” or “fussy.” It was only in the late 18th century that nice emerged as the polite and pleasant word we recognize today. Read more »

by Ken MacVey

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

This takes me to the glass half-empty/half-full trope. I have a different take on that trope. I think with a little reframing it tells a different story, illustrating a problem optimists and pessimists can share, and what to do about this problem. Here is the reframing:

There is a glass of water filled halfway to the middle.

The pessimist looks at the glass and says it is half empty. The pessimist goes on to say this is not enough, it won’t get any better, it might get worse with evaporation, maybe the water is contaminated, and we can’t do anything about it.

The result: nothing gets done. The glass stays filled halfway to the middle.

The optimist looks at the glass and says it is half full. The optimist goes on to say everything is good, we should count our blessings for having this nice crystal-clear water, everything is going to be great especially when we’re thirsty, there is no need to do anything, everything will take care of itself.

The result: nothing gets done. The glass stays filled halfway to the middle.

The activist looks at the glass and says: Fill it up!

The result: the glass gets filled up.

You see the problem that optimists and pessimists can share is that they both may rationalize not doing anything when something could get done. Read more »

Once there was a way, to get back homeward… Photo taken in Bruneck, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Lei Wang

I have often been envious of how characters in stories don’t seem to need to do dishes or laundry or buy groceries, except when it serves their story, like a meet-cute at the farmer’s market or perhaps a juicy conflict between two in-laws over the most efficient way to load the dishwasher. Otherwise, in novels and TV but especially in short stories and movies, the refrigerator fills itself and even eating is an afterthought: food is for pleasure, not necessity.

The boring things of life are given the ax, or no one would watch; imagine a maximalist reality show, each episode 24 hours long, corresponding exactly to a day in the life of someone that you play alongside your own life, minute by minute. Even if it were your favorite celebrity, would you really want to accompany them as they sleep for seven hours? I suppose there are such dedicated viewers out there and also such dedicated livestreams, like Firefox’s red panda web cams. I remember years ago coming across a crowdfunding campaign by a European twenty-something who decided to reduce his carbon footprint by sleeping or otherwise staying in his room all day. He was asking for money in order to do nothing, to contribute as little to the world as possible, and prove it via the most boring livestream. If I remember correctly, he had quite a few patrons—if only for the novelty of the idea.

What are the boring bits of life? Sleep, except for dreams. Chores. The things we have to do, and the things we do again and again and again. Life seems to be a constant battle against entropy, and we are losing. “I don’t identify as transgender… I identify as tired,” said Hannah Gadbsy in the comedy special Nanette. Don’t we all. This was the true punishment of Sisyphus: not the moving of the boulder or even the futility of it, but the day-in, day-outness of it all. We just showered yesterday and our hair is greasy already. The kitchen sink was empty a moment ago, but now there are no forks. The dog needs to be walked, again. Why can’t there be a pet that truly eats one’s garbage?

In The Quotidian Mysteries, a book on the mystical aspects of laundry and other domestic tasks, Kathleen Norris writes of how she found her way back to Catholicism through an Irish-American wedding in which, after the ceremony was over, she watched the priest doing dishes. “In that big, fancy church, after all of the dress-up and the formalities of the wedding mass, homage was being paid to the lowly truth that we human beings must wash the dishes after we eat and drink,” she wrote. “The chalice, which had held the very blood of Christ, was no exception. And I found it enormously comforting to see the priest as a kind of daft housewife, overdressed for the kitchen, in bulky robes, puttering about the altar, washing up after having served so great a meal to so many people.” She couldn’t quite understand the service, but she could understand eating, drinking, and housework.

Sacred is something that is “set apart” from the ordinary; something is sacred because it is not meant to be ordinary. But to treat an ordinary task as extraordinary is also to stand out from the ordinary. Read more »

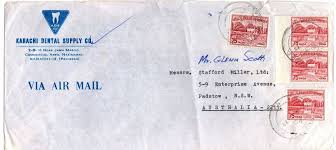

by Claire Chambers

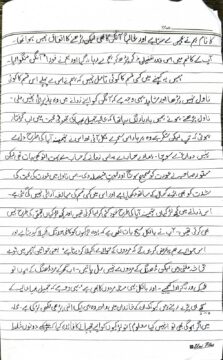

One day I went to my workplace in York, northern England, where I checked my pigeonhole as usual. An airmail letter lay in the metal box. Its postmarks were from Pakistan, and a man’s name and a Karachi address were scrawled on the back of the envelope. Because of the bimonthly columns I write for Dawn newspaper, I sometimes get email feedback. Occasionally people send me their books for review. But this slim package surprised me – especially when I broke the seal and pulled out four pages of Urdu handwriting.

One day I went to my workplace in York, northern England, where I checked my pigeonhole as usual. An airmail letter lay in the metal box. Its postmarks were from Pakistan, and a man’s name and a Karachi address were scrawled on the back of the envelope. Because of the bimonthly columns I write for Dawn newspaper, I sometimes get email feedback. Occasionally people send me their books for review. But this slim package surprised me – especially when I broke the seal and pulled out four pages of Urdu handwriting.

It had been years, probably over a decade, since I received a personal letter. My teenage sons and twenty-something Urdu teacher, Fareeha, claim they’ve never had one, apart from official dispatches. In this digital dunyā, what a privilege it is to get a letter, and that too a piece of mail which had travelled a long way.

This reaching out across distance and cultures reminded me of Saadat Hasan Manto’s ‘Letters to Uncle Sam’ – sharp, satirical notes dissecting international politics and American power. Balram’s letters to the Chinese Premier in The White Tiger also came to mind, with Aravind Adiga’s character telling Wen Jiabao about Indian corruption and inequality. My situation was different – I was in the UK, not the US or China – and the letter writer’s tone proved to be sincere rather than arch or ironic. Yet the impulse to communicate across borders felt equally urgent. In honour of Manto’s ‘Letters’ and to protect my correspondent’s anonymity, in this blog post I will call him Sami. I surmise, though, that he is much closer to my nephew’s age than my uncle’s.

I gazed at the pages, drawn in by the Urdu script and feeling enchanted that someone had created these words with such dexterity. I exulted even more at the newfound reading skills which allowed me to decode bits and pieces.

I gazed at the pages, drawn in by the Urdu script and feeling enchanted that someone had created these words with such dexterity. I exulted even more at the newfound reading skills which allowed me to decode bits and pieces.

I wasn’t linguistically equipped to easily decipher the whole letter. The first few lines were straightforward enough. His postal address was repeated, this time in Nastaliq. However, tellingly for this bibliophile, he did not provide any email or phone details. A standard polite greeting was given, and Sami went on to introduce himself. He explained he was a food science graduate but that his گھر کا ماحول – ghar kā maḥol or home environment – had instilled in him a love of literature. Here he name-checked two authors. The first was a writer whose detective novels I had been harbouring an ambition of reading in the original Urdu: Ibn-e-Safi. The other was new to me but my teacher Fareeha later told me he is brilliant: Ishtiaq Ahmed, who wrote spy novels as well as crime fiction. Sami had devoured all the thrillers by these novelists, both of whom are no longer alive. After these childhood peregrinations, he told me, his reading expedition had continued uninterrupted. Read more »