by Eric Feigenbaum

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

Now to be clear, I wasn’t a cop – but Rick was and when I would return to Seattle on a break from working in Singapore – the best way to spend time with him was to go on a “ride along”. To make it work better, Rick told people I was a plain clothes officer. To mitigate risk, I spoke little and appeared stoic.

We entered the Labor Ready office, prepared to find an altercation in progress, only to discover a 30ish, short, heavy-set Filipina lady standing in the waiting area talking to herself. The staff told us they had asked her to leave, but she didn’t really seem to understand them.

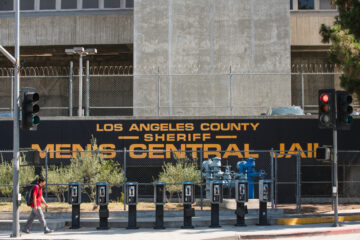

Rick asked the woman if she could follow him outside and she complied. Through the din of voices in her head, she was able to answer most of Rick’s questions – although not always accurately. We were able to ascertain the woman thought she was Princess Diana, but also had some sense she was reporting for a day-labor assignment. She was aware she wasn’t quite right and articulated that she needed medication – only she had run out and couldn’t afford more.

Protocol said Rick should have issued the woman a Trespassing Card and sent her on her way. That didn’t feel like the right thing to do for this very nice woman clearly struggling with her mental health and trying to make a living. Alternatively, he could have gone heavy and decided to arrest her for trespassing – another path to medication, only through the jail’s healthcare system. But then she would have an arrest on her record and been imprisoned for doing nothing more than talking to herself. Read more »

Donald Trump is a con man. He was that for a very long time before he entered politics. Because he is a con man, it is tempting for critics to describe his presidential victories as successful cons. However, I think that interpretation does not hold up. Because while Trump at his essence may be little more than a sociopathic con man lacking a sophisticated and flexible inferiority, voters and citizens are not simply “marks.” The electorate, especially one as large as the United States’ (over 73 million registered voters), is maddeningly complex. It reflects a stunning amount of views, ideals, fears, and nuance. And the catch is that while the elected government can never hope to fully reflect this complexity, it can unduly influence it.

Donald Trump is a con man. He was that for a very long time before he entered politics. Because he is a con man, it is tempting for critics to describe his presidential victories as successful cons. However, I think that interpretation does not hold up. Because while Trump at his essence may be little more than a sociopathic con man lacking a sophisticated and flexible inferiority, voters and citizens are not simply “marks.” The electorate, especially one as large as the United States’ (over 73 million registered voters), is maddeningly complex. It reflects a stunning amount of views, ideals, fears, and nuance. And the catch is that while the elected government can never hope to fully reflect this complexity, it can unduly influence it.

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

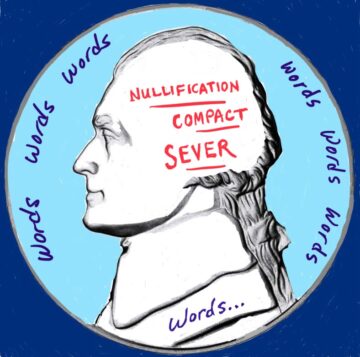

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

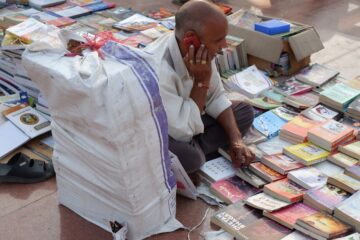

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called