by Anitra Pavlico

For millennia, humans have had a tradition of introspection and meditation. The Buddhist Dhammapada says that when a monk goes into an “empty place” and calms his mind, he experiences “a delight that transcends that of men.” The ancient Greeks exhorted one to know thyself. Montaigne wrote that the “solitude that I love and advocate is chiefly a matter of drawing my feelings and thoughts back into myself.” This was not so easy even in quieter times, but in the wired era, it has become almost impossible. When Bertrand Russell wrote his essay “In Praise of Idleness” in 1932, the threat to downtime and self-fulfillment was work: “I want to say, in all seriousness, that a great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work, and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.” This is still valid, as we work more than ever despite skyrocketing productivity thanks to technological advances. The trouble today, however, is that even our supposed leisure hours are spent on the grid, essentially ensuring that we never get a moment’s rest.

Over the past few years, numerous books and articles have sounded the alarm on how our online habits are affecting our mental health. Even individuals in the tech industry–including Tim Cook, the Apple CEO who prefers that his nephew not use social media, and Tristan Harris, former Google employee and founder of Time Well Spent, a group advocating for more sensible use of online tools—are joining the chorus. Against this backdrop, physicist, novelist, and essayist Alan Lightman has added his own manifesto, In Praise of Wasting Time. Of course, the title is ironic, because Lightman argues that by putting down our devices and spending time on quiet reflection, we regain some of our lost humanity, peace of mind, and capacity for creativity—not a waste of time, after all, despite the prevailing mentality that we should spend every moment actually doing something. The problem is not only our devices, the internet, and social media. Lightman argues that the world has become much more noisy, fast-paced, and distracting. Partly, he writes, this is because the advances that have enabled the much greater transfer of data, and therefore productivity, have created an environment in which seemingly inexorable market forces push for more time working and less leisure time. Read more »

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

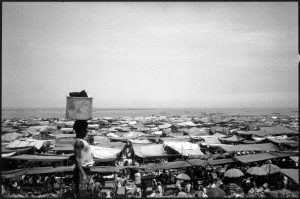

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

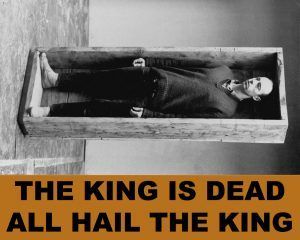

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.  In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.