by Carol A Westbrook

What song did you have in your head when you woke up today? Was it, “Oh Danny Boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling” as you recalled your St. Patrick’s Day celebration from the previous weekend?

Probably not. Chances are, the song in your head was not a slow, melodic ballad with simple lyrics, but a catchy, snappy tune. It might have been a line from a popular song, such as Lady Gaga’s “Rah-rah-ah-ah-ah” from her song Bad Romance, or Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Maybe it was an annoying commercial jingle “1-8-7-7-Kars-4-Kids.” Maybe you’re thinking of food, and getting hungry. O-Oh! How about some Spaghetti O’s? Or Rice a Roni, that San Francisco treat?

If you didn’t wake up with a song in your head, you probably have one after reading this far. I’ve just infected you with an earworm.

An earworm is a catchy tune that worms its way into your head when you hear or even read it, and then seems to get stuck there. And it’s really hard to get rid of. Many people enjoy these tunes that loop through their brains, much like they enjoy listening to music on the radio or their iPod. Others find them distracting. And for a very small number of people, they can be incapacitating. Read more »

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone:

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone: One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.

One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it. I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month

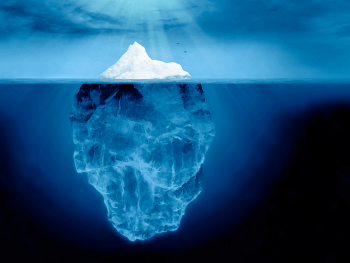

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month  From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and

From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and  The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

Just about everyone who visits the famous

Just about everyone who visits the famous