by Shawn Crawford

In 1987, Anderson University, an Evangelical school in Indiana, acquired 140 works by the artist Warner Sallman, including Head of Christ. You may have never heard of Sallman, but in terms of sheer sales and presence, his Head of Christ makes him the most popular 20th Century artist in America. Exponentially more popular than Warhol or Wyeth. If you are a Boomer or Gen X Evangelical, Head of Christ provided the definitive image of Jesus, in a way that you can never shake.

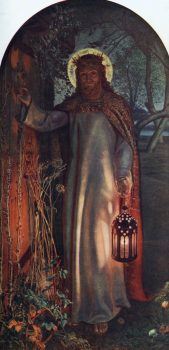

At my house, this was the only “art” hanging on the wall. Many of my friends could say the same. One of the wealthier families in our church also had a copy of Sallman’s Christ at Heart’s Door, with a heavy gilt frame and one of those fancy lights attached at the top to better illuminate Jesus trying to get in. The painting has obvious echoes to William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World without thePre-Raphaelite theatrics. Our Jesus did not wear a cape. And that beard needs a trim. As a freshman in college I learned Hunt had also painted The Awakening Conscience, a painting so erotic to my sheltered sensibilities I could not reconcile the two. I also stared at the reproduction in my British literature anthology for hours on end.

If you are wondering just how ubiquitous Sallman’s picture is, over 500 million copies have been sold since he painted it in 1940. That’s enough for every man, woman, and child in the U.S. with plenty left for Justin Trudeau to pass out to his disillusioned base. Oh pretty, pretty Justin.

The obvious question, “why is it so popular?” owes something to the Victorian borrowings from Hunt and Sallman’s training as a commercial artist at the Art Institute of Chicago. Paul V. Marshall, while a professor at Yale, remembers someone juxtaposing Sallman’s picture with the Breck Girl and suddenly understanding the appeal: “That was an epiphany for me.” You have to take your enlightenment where you can get it.

For Evangelicals, I think one of the appeals of Head of Christ is that it’s just the head of Christ. We couldn’t figure out how to deal with bodies, especially divine ones. So no shirtless Jesus, no bloody Jesus, no Jesus with naughty bits suited us just fine. If we all could have been disembodied heads, the world would have been a simpler, holier place. And that hair was to die for. Halfway over the ear was the limit of how far a boy’s hair could wander before whispers started in the youth group and parents contemplated an intervention. I circumvented this prohibition by going vertical; I got a perm and sported an enormous ginger ‘fro. Righteous on so many levels.

Handsome, white, otherworldly, Sallman’s Jesus evokes the nostalgia and sentimentality that would come to dominate Evangelical thinking. Like Doris Day, we wanted our savior in soft-focus, and we desired all of existence to order itself perfectly while we gazed heavenward.

In grade school, an art mobile came to town. We walked into a semi-trailer, and the length of one wall contained a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica. The searing images protesting the Spanish Civil War and its violence overwhelmed me. The guide explained the origins of the painting, and we heard the story of a Gestapo officer entering Picasso’s apartment in Paris during WWII. Guernica was hanging there. The officer asked, “Did you do that?” and Picasso replied, “No, you did.” At the public library, I scoured the shelves for books about Picasso and also became enthralled by surrealism and da Vinci. The Head of Christ would never look quite the same to me.