by Joseph Shieber

One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.

One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.

Simply put, the use/mention distinction is this. Let’s look at use first.

In order to choose an easy case, let’s say that the word I’m using is a noun. If I use a noun, I utter or write the noun in order to refer to what the noun refers to. So if I write “Neptune is the farthest planet from the sun in our solar system”, the word “Neptune” in that sentence refers to the planet Neptune.

If I mention a word, on the other hand, I am not using the word. Let’s take the case of nouns again. If I mention the word “Neptune”, then I’m referring to the word itself, rather than the object to which the word refers. So, for example, in the sentence ‘“Neptune” isn’t the only seven-letter planetary name’, I’m referring to the word “Neptune” rather than the planet Neptune.

Simple, right?

So why does it seem so hard for people to get it?! For example, there was the recent kerfuffle over an Augsburg University professor who, in discussing James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, had a student who quoted Baldwin’s use of the N-word. The professor, then, in discussing the student’s mentioning of the word, employed the word himself. Read more »

I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month  From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and

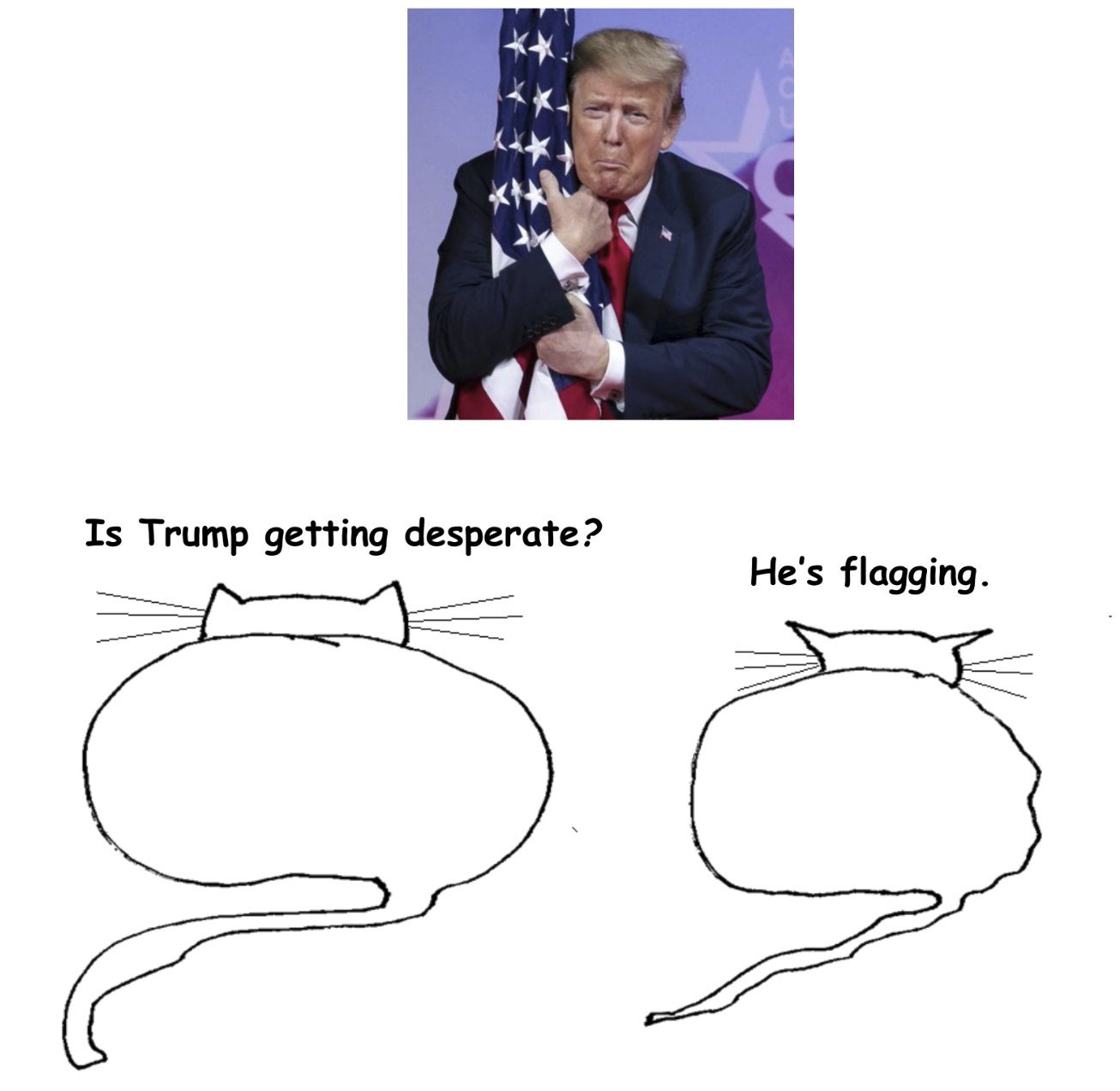

From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and  The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

Just about everyone who visits the famous

Just about everyone who visits the famous

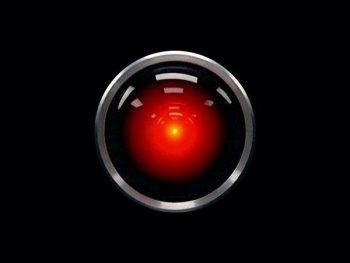

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,  The Anna Karenina Fix

The Anna Karenina Fix