by Michael Liss

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

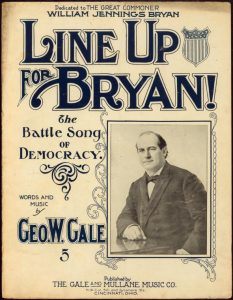

William Jennings Bryan was just 36 years old when, on July 9, 1896, he seized the Democratic Party’s Presidential nomination on the back of a single, electrifying speech, “Cross of Gold.”

Twenty-nine years later almost to the day, a haunted shell of his former self, he sat at the prosecution’s table, waiting for opening arguments in the Scopes Monkey Trial, unaware it would lead to his humiliation and ultimately hasten his tragic end.

In between, “The Great Commoner” was nominated twice more by his party, in 1900 and 1908, and served as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State from 1913 to 1915. He then threw himself into efforts for causes as diverse as women’s suffrage, direct elections for Senators, and Prohibition. In the 1920s, he shifted his primary focus to his faith, but remained a prominent figure among Democrats through the 1924 Convention, when he was literally heckled off the stage in tears while trying to broker a compromise on an anti-KKK platform plank.

Bryan is an enigma. He failed frequently, but got multiple chances where abler men were passed over. Contemporaries questioned his intelligence and the scope of his interests, yet the exacting, often arrogant Wilson put him in his Cabinet and gave him a free hand with Latin American policy. His durability might best be ascribed to his possession of two tremendous assets: First, he was arguably the best orator of his time, compelling almost whenever and wherever he spoke, and, second, he seemed to have a psychic bond with his base. As the historian Richard Hofstadter noted, while other politicians of that era may have sensed the feelings of the people, Bryan embodied them. His people stayed with him through his successes and his disappointments.

There is no modern politician to compare to Bryan, at least no one who would fit into any recognizable political species. But to understand him, even a bit, it’s worth examining a single six-week-long journey he took from Chicago’s Colosseum to New York’s Madison Square Garden in the summer of 1896.

You have to start with The Speech. Myth has it that “The Boy Orator of the Platte” emerged from complete obscurity. This is not true. He had been a Congressman, and a player in the Democratic Party for several years. His allies had been quietly organizing behind the scenes and gathering delegate pledges well before Chicago. But there’s no arguing that he could never have launched his candidacy without the extraordinary performance he gave.

The Speech is worth reading on its own. Theatrics aside, there are potent themes in there. Bryan hammered away at the moral, intellectual, and economic conflicts between labor and capital, and between Wall Street and Main Street. And, as virtually every listener in the hall that day knew, he was right. The deck was stacked against the common man. Unbridled capitalism, turbocharged by abundant political corruption, had ushered in a Gilded Age of huge personal fortunes. Steel, chemicals, railroads, oil and coal, zinc and nickel, meatpacking and banking—if there was money to be made, there were tough men to make it. There was an attitude amongst them that they were the winners in the Social Darwinism race and should therefore be exempt from living by any other man’s rules. Elected officials (properly compensated of course) largely agreed.

The humbler (and virtually everyone was humbler than Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Stanford, Frick, etc.) didn’t merit quite so many friends in high places. Labor found government willing and even eager to use (or let business use) muscle to keep them in line, and deaf to initiatives like workplace safety regulations, minimum wage, and child-labor laws. Farmers had an entirely different set of challenges: During a time of extended declines in commodity prices and land values, they found themselves hemmed in on one side by tariffs meant to protect domestic manufacturers, and squeezed by monopolistic pricing for machinery, storage, and shipping on the other. The scarcity of hard currency at a time where a bushel of anything bought less each year enhanced the appeal of Bryan’s Free Silver crusade.

The short-lived Populist Party had highlighted some of these issues in 1892, with some modest successes. Their candidate, James Weaver, carried five Western states and received Electoral College votes in a sixth, but there wasn’t yet a critical mass to take the movement national. Then, the Panic of 1893 intensified the hardships of the worker and farmer. Unemployment across the country shot up to crippling levels and farm prices fell yet again. Banks failed, and, with them, the deposits of working and middle-class families evaporated.

Opportunity was there for the right man with the right message, and, when Bryant walked onto that podium in Chicago, he knew it. Using words that are eerily modern, he defined the political universe: “There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, that their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up and through every class that rests upon it.”

Bryan insisted those masses occupied the same plane as the moguls. He professed to see no difference between the wage earner and his employer, the farmer and the grain trader, and the miner and “the few financial magnates who in a backroom corner the money of the world”—all were businessmen. All were worthy of equal treatment.

If he had built on that, he might very well have stitched together a winning coalition. But, operating with the peculiar myopia that was always to hamper his ambitions, he stumbled. First, he made a tactical mistake—having laid the groundwork for a broad-based attack on inequality, in the next breath he essentially abandoned every other idea to focus on silver as the magic bullet. He then compounded the error by blocking the Vice-Presidential candidacy of a moderate running mate, John W. McLean, who might have brought gravitas (and money) to the ticket. This alienated “Gold” Democrats (roughly one-third of the delegates) who were already a bit dubious about the rest of the platform. Back in William McKinley headquarters, there was considerable celebration.

His second mistake probably came from his gut. Bryan wasn’t really a coalition-builder—he was a man with a messianic sense of purpose and very distinct set of preferences. His heart was with the farmers: “You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.”

It’s the appeal of a purely sectional candidate, made all the more curious because Bryan had planned a whistle-stop rail trip to New York immediately after the Convention to accept his nomination, followed by a swing through New England.

Gaffe followed gaffe. He’s quoted as saying he was traveling East “in order that our cause might be presented first in the heart of what now seems to be the enemy’s country, but what we hope to be our country before the campaign is over.” His opponents pounced, and as much as his defenders (including some historians) claim that “enemy country” was “ripped out of context,” it sticks, particularly because he repeated it.

What happened next were even more unforeseen consequences, unanticipated disasters, and missed opportunities. Bryan’s rail route took him to dozens of cities and towns along the way, and in each one he was expected to give a speech and meet and greet. His voice, that magnificent Gideon’s Trumpet, weakened to barely a whisper. He and his wife Mary’s hands grew so swollen from being grabbed that eventually well-wishers were told not to touch the couple. And, to accentuate the misery, a massive heat wave gripped the country.

Bryan and retinue arrived in Manhattan on August 11th. The city was in no mood to celebrate; rather, it was in the grip of an epic human disaster. Nearly 1500 people died over a 10-day stretch, many small children. The tenements, crammed with immigrants and the working poor, without reliable indoor plumbing, many rooms without windows, without light or air, baked in the sun each day, making them virtually uninhabitable. People fled to fire escapes and roofs, some died in falls when they rolled over in their sleep, or when iron or masonry gave way. The streets were filled with dead horses, too numerous to be carted away before they started to decompose.

In this monumental catastrophe, official New York, in the thrall of Tammany and the monied interests, did virtually nothing. The idea of government intervention on behalf of the suffering poor and working classes seemed ludicrous to them. For days, their only visible presence was that of police shooting dogs and preventing people from sleeping in parks. Two men did jump in, Commissioner of Public Works Charles Collis, who instituted a plan of widespread hosing down of blocks in the poorest neighborhoods, and then-Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who arranged for the purchase and distribution of blocks of ice to the desperate. But that was it.

It was an astounding example of the very excesses of Capitalism that Bryan had been inveighing against, and an incredible opportunity. But he failed to seize it. Where was he? Giving what was certainly the worst major speech of his life. On August 12th, an estimated 12,000 New Yorkers trooped into sweltering Madison Square Garden to take his measure, and hear him demolish the defenders of the gold standard. They were quickly disappointed. Perhaps it was because of his weakened voice, perhaps it was for tactical reasons (he later said he was convinced the New York newspapers would refuse to report accurately what he said), but he decided to skip his usual extemporaneous, dramatic style, and read something prepared.

Whatever the motivation, it bombed, and after a few minutes, people started filing out. By the time he had finished droning, the Garden was mostly empty. The speech was panned by virtually every newspaper except the Hearst organ New York Journal, which, for business reasons, was an unabashed Bryan supporter. The after-effects were almost immediate. Few people came to the several receptions to meet the nominee—and even fewer of those were people of influence.

Bryan had squandered his best opportunity to convert the doubters, and his team of advisers quickly cancelled the rest of his Northeastern/New England swing. Curiously, no one seemed willing to use the extra time to regain the initiative, have Bryan and Mary visit some of hardest-hit neighborhoods, show compassion for those who official, monied New York seemed all too willing to ignore.

The couple left town for a visit with an old friend of Mary’s, and the moment passed. Bryan’s candidacy never really recovered. Between the “enemy country” remark, his forgettable speech, and his obsession with the Silver issue, he had defined himself as a parochial candidate without a strategy to appeal beyond his base. In November, McKinley swept the Northeast, and won decisively. In a rematch four years later, McKinley would expand his margin, including taking Bryan’s home state of Nebraska.

Progressivism would have to wait for abler champions with broader visions—people like Robert La Follette and TR. If there was consolation for Bryan, it may have finally come from the tens of thousands of his brethren who lined the funeral train route that brought his body from Tennessee to Arlington Cemetery. He never left his base, and they never left him.