by Joseph Shieber

The German philosopher Albrecht Wellmer died earlier this month in Berlin, on September 13 at the age of 85.

The German philosopher Albrecht Wellmer died earlier this month in Berlin, on September 13 at the age of 85.

A member of the “second generation” of the Frankfurt School, Wellmer was a Ph.D. student of Adorno’s, a professorial assistant of Habermas’s, and a colleague of Arendt’s.

Although Wellmer wrote both of his dissertions (the Promotionsschrift and the Habilitationsschrift) on topics in the philosophy of science, he soon turned to ethics and critical theory, and later to the study of the philosophy of language and the philosophy of music. He held positions as a professor at the New School for Social Research, the Universität Konstanz, and the Freie Universität Berlin. In 2006, he was awarded the Theodor Adorno Prize by the city of Frankfurt.

Infinitely less significant is that Wellmer also gave me my first job in philosophy, as a wissenschaftlicher Hilfsassistent — basically a teaching assistant — in the Institute for Hermeneutics in the philosophy department at the Free University of Berlin. I worked under him from 1994 to 1997, including serving as a teaching assistant for the lectures that were published in 2004 as Sprachphilosophie: Eine Vorlesung.

One of the pleasures of being a teaching assistant for Wellmer was that I was allowed to participate in the invitation-only, biweekly discussion group that Wellmer held with his assistant professors, Ph.D. students, and teaching assistants.

Generally, probably about fifteen people or so attended those discussions. During my time there, I remember our having tackled — often over the course of a semester or more — Hegel’s theory of tragedy, Brandom’s Making It Explicit, Derrida’s Signature, Event, Context, and Heidegger’s Nietzsche volumes.

As a sample of the high level of the participation at those biweekly meetings, here’s a — surely incomplete — list of the assistant professors and doctoral students who participated during the three years I attended the group who have since continued on to careers in philosophy: Eduardo Fermandois, Andrea Kern, Christoph Menke, Juliane Rebentisch, Sebastian Rödl, Ruth Sonderegger.

I remember at least one meeting with the discussion group in Wellmer’s airy, spacious apartment in Berlin, and how I was struck by the pride of place that Wellmer’s piano enjoyed in the apartment. Wellmer was, himself, quite an accomplished pianist, and it was evident how important music was to him — an abiding interest that he shared with his dissertation director, Adorno.

Wellmer’s deep connection to music got me thinking about some of the ways in which music and philosophy are analogues.

There is the distinction between composers and performers. Some philosophers — those who publish articles or books — are the composers of philosophy’s etudes and symphonies. Other philosophers focus more on performing: conveying the classics or the “new music” to new generations of budding connoisseurs.

There are the questions of relevance: Why waste your time with that? But how will you earn a living?

There are concerns that the field is overly focused on a too-narrow Western canon and that the major figures in the field lack an appropriate appreciation for the contributions of non-Western or other traditionally marginalized figures.

Finally, there is the fact that not everyone has an ear for it. Some can hear the beauty and the pathos, the terror and the joy. Others just hear noise.

For the lucky few for whom it has resonance, though, philosophy — like music — can be a source of consolation in dark and debased times.

I noted that some philosophers were composers while others were performers. Wellmer was both: a composer and a performer — both of the classics and the “new music” — whose contributions deserve to be remembered.

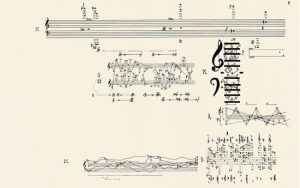

In his last book, Versuch über Musik und Sprache, published in 2009, Wellmer assessed Adorno’s views on the place of music in society, and contrasted them with his own position.

According to Wellmer, Adorno was mistaken in seeing music as, at best, “the promise and placeholder of a reconciled, of a free society”. Adorno, according to Wellmer, was prevented from appreciating the true role of music because of Adorno’s pessimism about the inability of the “hoodwinked” masses to appreciate genuine art.

In contrast, Wellmer suggests that music in fact

opens itself to the world and — without sacrificing its autonomy or its historically situated compositional quality — finds a connection with the horizon of experience of contemporary listeners. It does so not in order so much to fraternize with them, but in order critically to engage with their experiences and perceptions.

Sounds like philosophy to me.