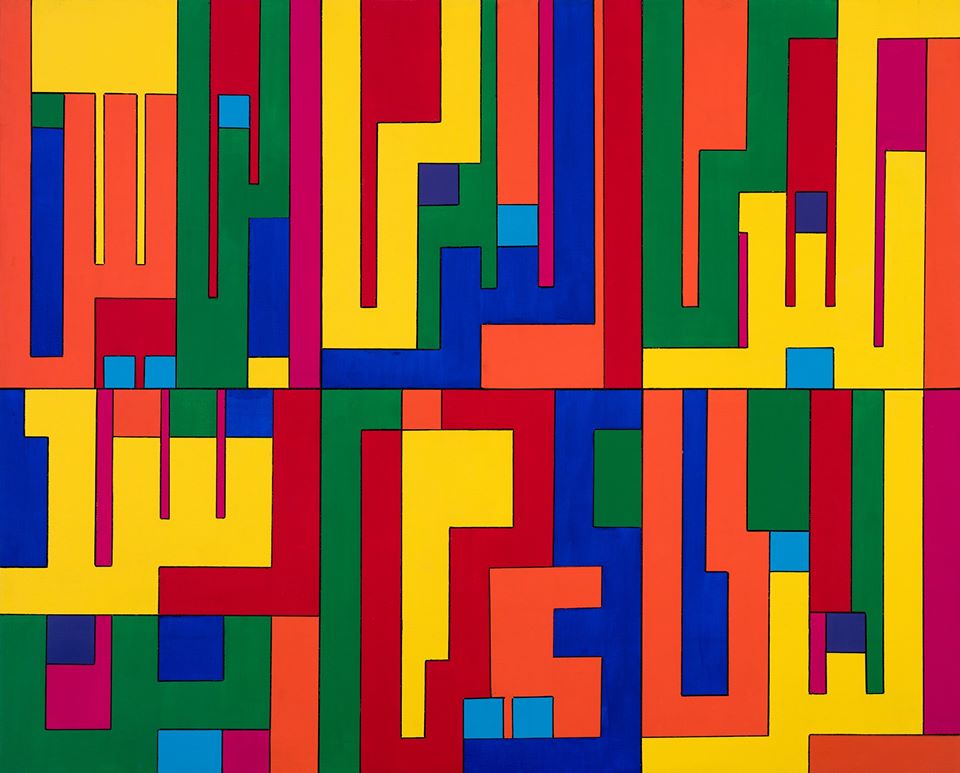

by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met here. I ask you to support artists wherever and however you can.

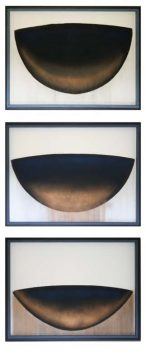

Peter de Swart, works on paper: Triptych

The triptych form is associated with religious painting. It first appeared as a feature of early Christian art and became popular for altar paintings and devotionals during the Middle Ages. While Peter de Swart’s Triptych is not overtly religious, it emanates an undeniably religious or spiritual aura. It is, in a word, numinous. To encounter this painting is to witness a sacred transaction. You’d have to be a stone to look at it and not experience a yearning for the divine. Why, apart from its rearticulation of the history and symbolism of the triptych form, is that?

It must have something to do, first of all, with the simple purity of the object pictured, which appears to be a bowl of some sort. Bowls are one of those inventions (like scissors or chopsticks or the hourglass) that we got right the first time. They were perfect the moment they appeared. In the bowl, function lives harmoniously with form. Its shape is so ideal as to be almost Platonic. Furthermore, bowls are used to prepare and serve food and drink, which means that they give sustenance, enable shared meals, and consequently help to strengthen communal bonds and deepen human relationships. Finally, bowls are vessels. Like hands and pockets and ships, they hold and contain and convey things—but they are not grasping like hands, nor like pockets do they secret away their contents, and they don’t trade goods and gold like ships. Quite the opposite, in fact: Bowls are generous, open, gratuitous. They give away the things they hold.

All of these attributes (form, use value, ethos) lend bowls a quasi-spiritual redolence, but they do not make bowls sacred. If this triptych depicted a bowl no different from any other bowl, then its effect would be decorative rather than numinous. This bowl is special. Again we must ask: Why is that? Read more »

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. Dedication

Dedication

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology