by Thomas O’Dwyer

It seemed like a good idea. What better time than a pandemic lockdown to tackle again a feat that no human has so far accomplished and yet which seems to require nothing more than a comfortable chair, fingers that can turn pages, and a slice of uninterrupted time. It was another perfect opportunity to try just once more to read Finnegans Wake. It’s a book. How hard can it be? There are no spoilers here; it’s hard, and I failed and will most likely never try again.

When he published Finnegans Wake in May 1939 after 17 years writing it, Joyce said that he wrote the book “to keep the critics busy for 300 years” and “the only demand I make of my reader is that he should devote his whole life to reading my works.” So far, so good – they’re still going strong, critics and masochistic readers, 81 years later. But most unusually, the critics began trying to decipher the Wake before it was even written. In 1929 Joyce’s friend Samuel Beckett and a group of writers produced a symposium on what Joyce then called Work in Progress. This was ten years before the final Wake emerged. They published their erudite musings in a booklet ominously titled Our Exagmination Round His Factification Of Work In Progress. We readers can’t say we weren’t warned.

Jerry Seinfeld is unlikely to pose the question, but here it is: “What’s the deal with Finnegans Wake?” First, what is it? The Wake built on Joyce’s already formidable reputation for reconstructing the English language – Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Dubliners, and the astonishing saga of one insignificant man’s ordinary day in Dublin, Ulysses. Finnegans Wake was something else – so dense, incomprehensible and apparently pointless that even today it is perfectly respectable to argue that it was a giant hoax which Joyce produced for his own amusement and to confound his critics.

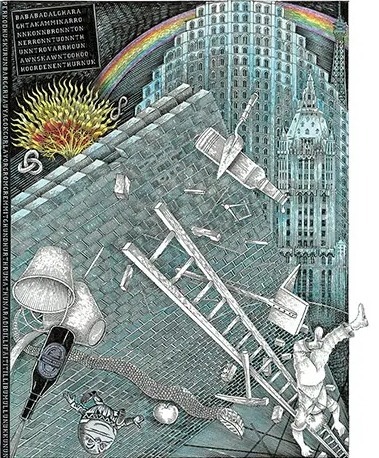

I first came across Finnegans Wake when a hardback copy fell on my head when I was exploring the first public library I had joined as a young teen. Babababadalgharag… (I’m not going to fill more space with this full hundred-letter thunderclap word from the first page of the book, which is the sound of the giant Finnegan falling to earth). With hindsight, being banged on the head was an appropriate introduction to the Wake, though I had no idea what it was. I picked it up, opened a random page, and concluded it was written in some foreign language, perhaps Finnish or Portuguese. Only the title was recognisable. Finnegan’s Wake was a well-known Irish ballad popular at drunken pub parties and wakes (often the same thing). A building worker, Tim Finnegan, has fallen from a ladder and died. Friends gather to wake him in old Irish tradition as he lies there with “a gallon of whiskey at his feet and a barrel of porter at his head.” As the revelry roars on Finnegan suddenly sits up in the coffin and bellows, in the version by the Dubliners folk group, “Stop whirling me whiskey ’round like blazes; be the thunderin’ Jaysus, d’ye think I’m dead?”

So what had all this to do with the thick tome written in – (Norwegian?) – with eccentric punctuation and no chapters. Who knew? I put it back on the shelf and checked out some “normal” books. I had just read my first adult novel, a book left behind by a visitor to our house. This was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch, and I had found it both delightful and obtuse. I misunderstood most of the narrative and misread the dialogue but was excited by the challenge of adult literature. I chanced upon Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in secondary school and was mildly interested because Joyce’s Jesuit school, Clongowes Wood, was not far away and the snarky ruthlessness of the Irish religious teaching orders was too close for comfort. I tossed the book aside, autobiography was boring, but I was impressed by the startling final sentence: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” It felt like an inspiring leitmotif as we stepped into the next phase of life, undergraduate pretentiousness.

Young Joyce and his student friends had rented an abandoned 19th-century defensive tower, one of many which had been built on the coast to warn of a possible invasion by Napoleon. This Dublin Martello tower has been rendered immortal as the setting of the first chapter of Ulysses. We couldn’t aspire to a rented tower, but in scruffy rooms on the banks of a Dublin canal, three of us lived out the eternal student cliches. Sprawled on beanbags and broken chairs with flagons of cheap cider, we debated with arrogant certainty the ancient questions of philosophers, the non-existence of gods, the mendacity of priests and politicians, and the works of Flann O’Brien, Virginia Woolf, and Jimmy Joyce. Ulysses too is notorious for its difficulty, but since we were young and enthusiastic, and the book had the cachet of being officially banned in Ireland, we slowly made our way through it with success. Ulysses has a structure, a plan based on Homer’s Odyssey, and its characters and streets belonged to a city we knew and loved. It had 18 chapters, like a regular book, and titillating obscenities to stoke student libidos. After all, we were supposed to become literate, even literary. Where better to start than with a rejected and exiled fellow countryman whose rebellious nature we admired and whose international fame we were proud of. Joyce made modernism palatable and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse readable.

But there was one book that dare not speak its name. Finnegans Wake. I know that, individually, each one of us dipped into it, for there was a copy lying around the apartment. But no one would raise the topic for discussion because no one knew where to start without sounding like an idiot. The Wake mocked even the basic concept of “start at the beginning” for the very first sentence merely runs on from where the book’s last sentence leaves off. The last sentence of the book is “Away a lone a last a loved a long the” and the first sentence on page one is “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

Since its publication, countless would-be readers of Finnegans Wake have thrown in the towel after a few pages and dismissed it as perversely unintelligible. The legend still endures that no mortal has ever finished Finnegans Wake. That’s an obvious exaggeration since there are shelves full of commentaries all over the world, even alleged translations, so some literary mountaineers must have moved beyond base camp. When we first heard that Anthony Burgess, of Clockwork Orange renown, had translated the Wake into French, we assumed he would be enthroned somewhere as a literary deity. Even more astonishing, in 2013 a translation by Dai Congrong, a professor at Shanghai’s Fudan University, became an unexpected hit in China. Fennigen de Shouling Ye sold out its first run of 8,000 copies on publication day.

In 1944, a young professor of mythology and literature, Joseph Campbell, went on his own Hero’s Journey and wrote the first guide to the labyrinth of the Wake. A Skeleton Key takes Joyce’s unintelligible stream of words page by page and attempts to strip away at least some layers of obscurity with copious footnotes and comments in parenthesis. The notorious opacity of Finnegans Wake depends not only on its verbiage, which appears to have been formed by tossing English into a blender with 60 other languages and smearing the resulting mess across 600 pages. If the reader knew what the plot is about, perhaps that would help with deciphering the language. No such luck. Ulysses was a daytime stroll through the streets and minor events of a city, and Joyce himself has said that Finnegans Wake is a book of the night, a dream with the moods and shifts and illogicality of dreams.

But who is dreaming? Is it Finnegan the hod carrier who falls from his ladder on the first page and observes his own wake before being resurrected to start a new cycle of life? That phrase “commodius vicus of recirculation” in the first sentence of the book is an early example of the multiple layers and associations hidden in almost every word and non-word of the Wake. It even contains Joyce’s entire theme – recirculation, history endlessly repeating itself, conception, birth, life, death, decay. “Vicus” nods to Giambattista Vico, a 17th-century Italian philosopher whose ideas also underpinned much of the historical vision in Ulysses. Vico argued in his influential Scienza Nuova that civilisation evolves in a recurring cycle (ricorso) of three ages – the divine, the heroic, and the human. Each period exhibits distinct political and social features and can be characterised by specific figures of language and what today we call memes. In the novel, Finnegan himself evolves from an ancient Celtic hero into the pedestrian figure of HCE, Henry Chimpden Earwicker, an innkeeper living in a Dublin suburb, Chapelizod, with his wife ALP, Anna Livia Plurabelle. (Chapelizod is named for a chapel of Isolde, the tragic heroine of Celtic and Germanic legends). Anna Livia is a personification of Dublin’s famous River Liffey. It changes through the novel from the fresh young mountain spring where the river rises, to a matriarchal and serene flow through Chapelizod where she lives with HCE, to an increasingly aged and ragged estuary where the river meets the sea (“bend of bay”) amid industrial ugliness. From the sea, the water evaporates before falling in fresh new raindrops into the mountain spring, and Anna Livia’s ricorso of life and rebirth is complete.

Many years ago I moaned to a friend in an Irish pub that I had just given up on reading the Wake for the Nth time and would probably never try again. “There’s a reason you can’t get through that thing,” he said. “You can’t get past the first word in the title without starting a feckin’ argument.” He was right. It’s Finnegans Wake. “No apostrophe,” I would wearily tell writers when I worked as a copy editor.

“What? That doesn’t make sense.”

“It doesn’t have to. It’s James Joyce. If it’s the folk song; apostrophe.”

There’s ambiguity in them thar Finns. We have the wake itself, the sending off of dead Finnegan. Or and also, we have a waking of all Finnegans. We simply state the fact that Finnegans wake, no big deal. Perhaps we are ordering them to wake up, in which case maybe there should be an exclamation point. And don’t forget the very name Finnegan contains all the ricorso philosophy of the round-headed Neopolitan Giambattista Vico. We finish – fin – and then start, again. Fin again. Thus begins your 600-page river journey along Anna Livia Plurabelle, and you haven’t even opened the damn cover yet.

I have managed to read Clarice Lispector’s Agua Viva and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, and am now quite good with Ulysses. I once ploughed through Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics. I have been unable to read Finnegans Wake, not for lack of effort – a few times I even spoke in public about it – but I have finally decided it’s not my fault, it’s Jimmy Joyce’s. He may have been a genius, and very punny, and Dubliners is a treasure. But in the end, he’s an old fraud who conned us all. There may be much meat in Finnegans Wake, but not much merit. It’s a midden (he even used that word) into which he dumped all the words, ideas, newspapers, toilet paper, folklore and food labels of early 20th century Dublin. Into it, he emptied all the bric-a-brac and junk of the city’s pawnshops, flea markets, antique stores and attics. He then flattened it with a linguistic steamroller and said to us, “It’s full of interesting layers and meanings. You just have to look for them for 300 years.”

Of course, you can find some gems of value, some lovely figurines in the midden. There is a scene towards the end (of the beginning) of the Wake which can transport any nostalgic exile back to long-gone dear old dirty Dublin. It evokes dusk sinking over the Liffey as it nears the sea, the brackish water, the smell of salty grime in the chill air. Two washerwomen have been doing their laundry by the quayside, their distant gossip and griping fading and falling in the breeze. They stiffly rise to head home but “my foos won’t moos” (me feet won’t move) as bats swoop around and gulls and hawks cry. Joyce himself loved this passage – it is the only part of the Wake he has been recorded reading aloud. His voice reveals what may be one mystery of Finnegans Wake, the magic in the lilting Irish music of the words, not in their shape on the page.

When Dublin in 1988 raised a sculpture in the city centre, representing Anna Livia Plurabelle surrounded by water, ever-irreverent Dubliners immediately named it “the floozie in the jacuzzi.” It’s the fun in the pun that counts and Finnegans Wake is most often groaned over for Joyce’s relentless overuse of this tiresome device, for the book is stuffed with them. The puns are occasionally funny, often clever, even profound, but mostly annoying. What, one might ask was his point is representing life as “a crossmess parzle”? This is a pun on both Christmas parcel and crossword puzzle and is about as profound as Forrest Gump’s chox of bocolates. It’s easy to mock Finnegans Wake after one has hurled it (again) across the room. Anger and scoffing and defensive excuses have been the book’s closest companions not since it’s birth but from its conception. In Samuel Beckett’s symposium on the Work in Progress, the Exagmination Round His Factification, even the earnest literati who put it together, including William Carlos Williams, Stuart Gilbert and Rebecca West, ended the booklet with one Essay by a Common Reader. “I have tried to penetrate the maze of printing that Mr Joyce would evidently have us regard as a serious work. … One is struck by a certain significance in his method of shading off actual words and inventing others. Is Mr Joyce’s hog Latin making obscenity safe for literature? Or is he like an enormously clever little boy trying to see how far he can go with his public?”

Going one step better, Beckett ended the booklet with a fake letter mocking Joyce’s deconstructed English punning.

A Litter to Mr James Joyce

Dear Mister Germ’s Choice,

In gutter dispear I am taking my pen toilet you know that I have been reeding one half ter one other the numboars of “transition” in witch are printed the severeall instorments of your “Work in Progress”.

You must not stink I am attempting to ridicul you of to be smart, but I am so disturd by my inhumility to onthorstand most of the impslocations constrained in your work that … I am writing you, dear mysterre Shame’s Voice, to let you no how bed I feeloxerab out it all.

I would only like to know have I been “out of the mind gone out” and unable to combprehen that which is clear or is there really in your work some ass pecked which is Uncle Lear?

Please froggive my t’Emeritus and any inconvince that may have been caused by this litter.

Yours veri tass,

Vladimir Dixon