by Joseph Shieber

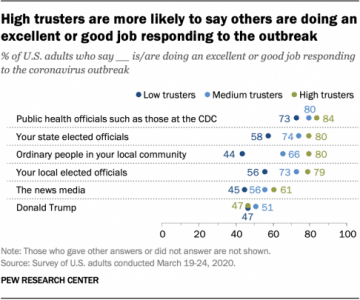

One of the heartening ramifications of the otherwise devastating Covid-19 pandemic has been the public’s high level of trust in science and expertise. As a March 19-24 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center indicates, over ⅔ even of low-trusting people surveyed trust public health officials to do an excellent or good job in dealing with the outbreak.

In fact, even corporate Twitter accounts for shaved meat products can boost their following by amplifying the experts:

This increased trust in scientific expertise is part of a growing trend. A Pew Research study in 2019 found that, since 2016, when less than ¼ of the public had “A great deal” of confidence that scientists act in the best interests of the public, by 2019 more than ⅓ of the public expressed “A great deal” of confidence in the actions of scientists.

The rising levels of trust in scientific expertise stand, however, in stark contrast to the current UIS Administration’s flagrant disregard of science. Indeed, the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School and the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund have tracked 417 “government attempts to restrict or prohibit scientific research, education or discussion, or the publication or use of scientific information” since the 2016 election.

Given this, it was puzzling for me to read stories like The Guardian’s April 23 article by Hannah Devlin and Sarah Boseley entitled “Scientists criticize UK government’s ‘following the science’ claim”. My immediate reaction was, If only US decision-makers even respected scientific expertise enough even to pay lip-service to it!

Now, many of the points made in this article — as well as a number of related opinion pieces and op-eds — are good ones.

For one, the fact that there are different forms of disciplinary expertise that may result in different perspectives — and different analyses — of the complex challenges posed by Covid-19. Epidemiologists, public health professionals, medical doctors, microbiologists, economists, political scientists, sociologists … all have differing expert skills to bring to bear on the outbreak. Furthermore, the different expert cultures in these very disparate disciplines may lead practitioners within those disciplines to view the pandemic through distinct lenses — making interdisciplinary communication quite challenging.

A second potential worry is that appeals to science may merely be ploys by political decision-makers to set the stage for shifting blame onto scientific experts should the political decisions lead to poor outcomes. For example, Devlin and Boseley quote University of Edinburgh political scientist Prof Christina Boswell as worrying that, “If things go wrong – and the curve gets too steep – it will be the scientific advice that is to blame.”

However, I’m worried that the experts fretting about government appeals to science may themselves be sowing the seeds of a damaging backlash against scientific expertise.

For example, in an April 28 op-ed in The Guardian, the University of Cambridge sociologist Jana Bacevic writes this in a critique of claims that government policies are shaped by “the best science available”:

… there is no such thing as the “best science available”. Scientists regularly disagree about different issues, from theoretical approaches to methodologies and findings, and decisions about what kind of scientific advice is taken into account are highly political. The individuals, disciplines and institutions that are invited to the table reflect the distribution of research funds, prestige and influence, as well as the values and objectives of politicians and policymakers. When it came to austerity, for example, the former coalition government ignored the warnings of many macroeconomists in favour of evidence that supported its worldview. If there is no “magic money tree”, there is certainly no magic “best science” tree either.

There is a great deal to unpack just in this passage. One of the points Bacevic makes in it is that political considerations can affect which disciplines are asked to weigh in on policy decisions: “decisions about what kind of scientific advice is taken into account are highly political. The individuals, disciplines and institutions that are invited to the table reflect the distribution of research funds, prestige and influence, as well as the values and objectives of politicians and policymakers”. Another point is that political decision-makers can cherry-pick evidence to support their preferred positions, as in past instances in which “government ignored … warnings … in favour of evidence that supported its worldview”.

What worries me, however, is the first line of Bacevic’s critique, the bald assertion that “there is no such thing as the ‘best science available’” and Bacevic’s support for this claim on the basis of the fact that “scientists regularly disagree about different issues”. These claims strike me as misleading at best, as well as dangerous in the aid and comfort they provide to those who would seek to ignore scientific expertise in reaching better policy decisions.

First of all, in many cases it’s simply false that there is no such thing as the best science available. If I have type 1 diabetes, the best science available suggests that it should be managed with insulin therapy. The best science available suggests that the earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old — and not, say, approximately 6,000 years old. The best science available suggests that the current global warming trends are real — and human-caused.

Suppose, however, that you think that Bacevic didn’t intend to deny that there are some areas in which it makes sense to speak of “the best science available”, but rather that she instead meant to suggest that it makes no sense to speak in that way regarding research areas in which scientists disagree. The problem with this suggestion is that it’s always possible to find at least some scientists who disagree — even about well-established phenomena. This is the basis of the familiar “teach the controversy” ploy by which opponents of settled science — like anthropogenic climate change or evolution by natural selection — attempt to advance their anti-science agendas.

There are important subtleties that Bacevic’s rejection of the locution “the best science available” elides. In particular, as Matthew Yglesias put it in a piece for Vox,

… it’s important to recognize that the partisan clash over the science of coronavirus is not the same as that over issues like climate change and air pollution.

Scientists have barely begun the work of understanding this virus, so they don’t have decades of research and data to rely on to answer our questions. … Scientists spend years gathering the data and information necessary to produce increasingly better answers to complex questions.

We should be careful, in other words, to distinguish areas of science in which scientists have had the time “to produce increasingly better answers to complex questions”. However, the criteria for doing that aren’t as simple as finding areas of unanimity.

In fact, the alternative to unsettled science isn’t NO science, but more and better science. For example, it is hard to see how policy makers can proceed with medium- or long-term planning without models for how the pandemic will likely progress. We may well come to recognize that some models on which local, state, and federal government agencies have relied are poor. The correct way of coping with those less-than-ideal sources of information, however, is precisely the way that science teaches.

Scientific thinking involves coping with uncertain information. No single source of data in scientific investigation is dispositive; no single piece of evidence cries out, “Here I am, the answer to the question you’ve been exploring!” Rather, scientific investigation always involves assessing evidence and weighing the extent to which it bears on the questions under consideration.

The answer to the problem of bad faith uses of science — or, in some cases, good faith uses of bad science — on the part of politicians is this. Better scientific reasoning. Better statistical analyses.

As Kelsey Piper, writing in Vox, recently put it:

Ultimately, the problem may not be that some models are inaccurate. It was predictable that some models would be inaccurate, with the situation as confusing as it is. There are dozens of models, and ideally we’d be doing something like aggregating them and weighting each according to how well it has performed so far in predicting the crisis.

Somehow, I think it’s fitting that Steak-Umm should have the last word: