by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

The vocabularies of sports and war feel natural for describing arguments and their performances. From battle, we describe arguments as swords, as they may have a thrust, may cut both ways, and may be parried. A case, further, can be a full-frontal assault, and we may rush once more unto the breach. There are defensive positions and rear-guard actions. One’s best arguments are one’s heavy artillery, and one may lay siege to viewpoints. And one may, on the sports model, score points or score own goals with successful or unsuccessful arguments, respectively. One may play soft- or hardball. Powerful arguments are slam dunks or home runs, and good rebuttals are counterattacks. Or one may change the subject with a punt. There’s no doubt that our vocabulary for describing what happens when we argue is thick with this metaphorical idiom. The question is whether it is a good thing or not – does the vocabulary of adversarial contest distort our relationship with argument? We hold it need not, but there are some concerns that must be addressed.

The first concern is that sport and war metaphors are misplaced because they presuppose (and seem to endorse) hostility between arguers, and this hostility has objectionable consequences. One’s objective in a game and in a war is to win, to defeat the adversary. As the saying goes, all is fair in love and war, so (leaving love aside) when we turn to the context of argumentation, the metaphors make it difficult to see what would be wrong with using all available means to win in argument. However, unlike in a war, successful argument depends upon arguers following the rules. Further, when one loses an argument, one nevertheless learns something about one’s views. And one may change one’s mind for the better. Losing an argument can be beneficial to the loser. The war and sport metaphors, so the objection goes, fail to recognize this complex of features of argument; for that reason, they are inapt. Read more »

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality.

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality. The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,

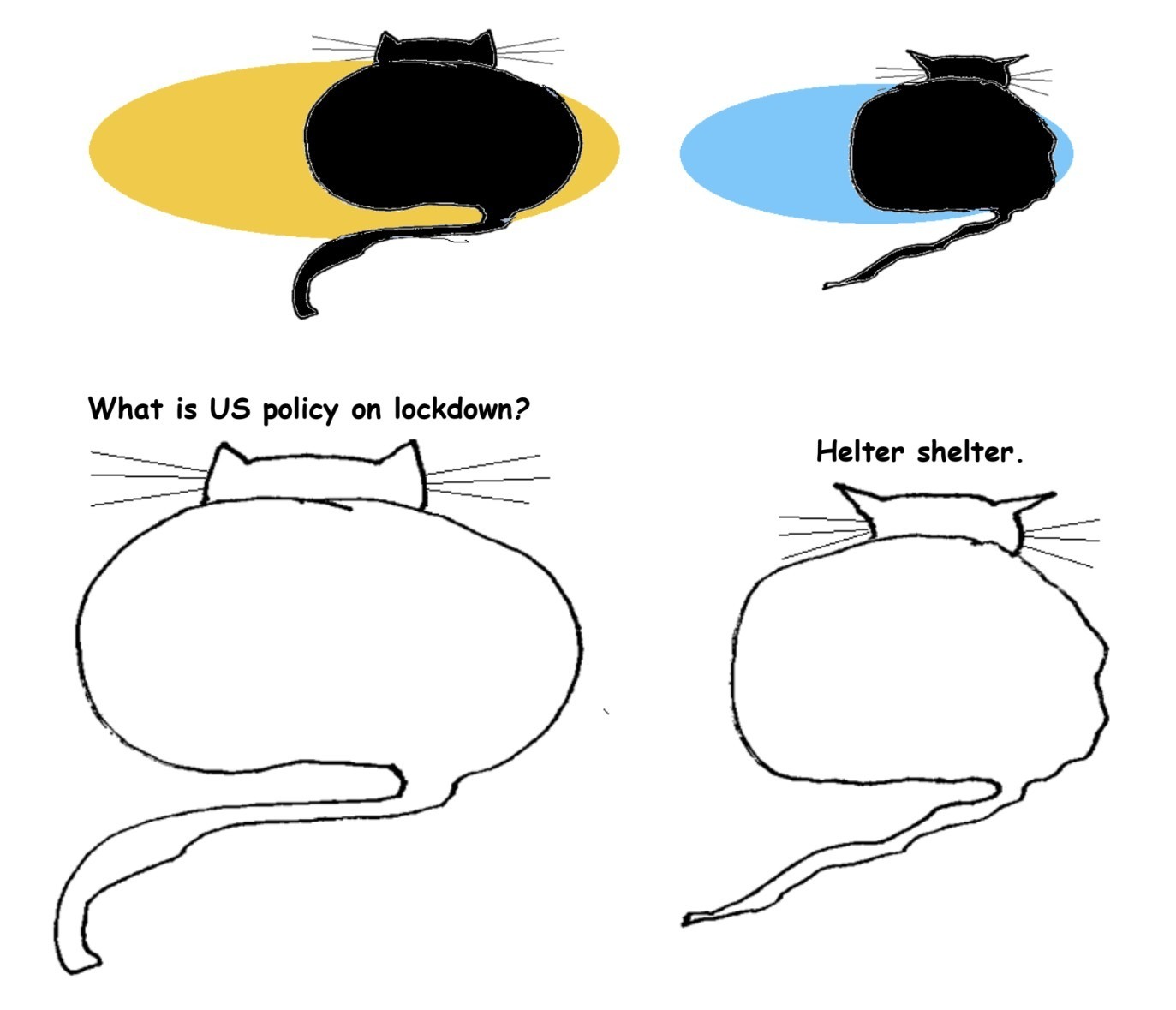

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,  What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it?

What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it? Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague. What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story. One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.