by Liam Heneghan

When I was a child growing up in Dublin, a friend dropped her pet hamster on the kitchen floor. The animal survived but thereafter he could only walk in circles. As the hamster got older, the circles got wider but like a ship permanently anchored to shore it never got particularly far.

Like most children, I had taken a fall or two and because I was a worrier I felt concerned that like that hamster I would never travel very far. Though I did, indeed, travel and I am now thousands of miles from home, I still think of my life as occurring in a series of ever widening circles.

At first, I was confined to our back garden. We lived in the Templeogue Village an inglorious suburb on what at the time was a trailing edge of Dublin. Over the garden wall were farm fields and farther off were the Dublin Mountains.

Sure enough over the years, I explored the fields and when I got a little older, I would cycle into the foothills of those mountains.

Now there was one hill in particular that I was drawn to: officially called Montpelier Hill it is also called The Hell Fire Club. The story was that a structure built there in the early 1700s as a hunting lodge for delinquent aristocratic youth had also been used by them for somewhat darker practices. One night the devil himself showed up there at a card game. In the hubbub that followed, a candle was knocked over and the lodge burned to the ground. By the time I started to cycle there, The Hellfire Club was an innocuous forestry plantation. The burned lodge remains.

Shortly after I walked up Montpelier Hill first, I noticed that off the trail were a series of large burrows. Were they rabbit holes, I wondered—literally for the largest-assed rabbits in existence? No, I was told, these were badger setts!

Badgers are common enough in Ireland, of course, but Dubliners do not see them very often, as they are crepuscular. You can tell if a sett is active by placing twigs over the opening during the day and seeing whether the twigs have been moved during the night. So I set about this task: laying the sticks in the evening and cycling up in the morning to see if they had been moved. Several of the burrows were indeed active and so I determined to go and see the badgers at night.

This was my first sense of being proximate to a truly wild animal.

At some point in all of this, I told someone—I think it was my dad (memory being what it is) —what I was doing.

“No, no…” this person—who may or may not have been my dad, said—“you don’t want to be caught by badgers. Their bite is so ferocious that once they sink their teeth into you they don’t let go until they hear the bone break!”

“Are you fucking joking?” was my response to this person (if it was my dad the response was internal, as he is not a crude man).

“It’s always handy,” opined this expert (perhaps my dad), “to carry a stick into ‘Badger Country’”

“Badger County…. jaysus” (I opined internally, probably.)

“What you do is this: when they bite, break the stick over your other leg, and they’ll think they’ve broken the bone.”

Cool, cool…! Terrifying!

Badgers were everything that I was not: bold, ferocious and tenacious (especially when it came to pulverizing bones). A mildly alarming animal living on a hill with an especially dark history.

Were badgers there, I wondered, when the devil revealed himself to the card players?

I am sad to say that such was the timorousness of my youth I abandoned my badger hunt.

Several years later, in my early 20s, my orbit expanded again, and I was working up in Donegal, in the National Park there, as a contract entomologist. I would walk miles across forest and bog during the day, and walk back at dusk sweeping with a net for the flies I was interested in at the time. Shortly after arriving in the park, I saw evidence of badgers in the valley. This reawakened my old interest.

One evening I saw one—an old broc—in the distance. It was twilight, the sun was setting behind the mountains, and there he was by a river. He was jumping up and down on a little mound of earth that overhung the water. I thought he was dancing. How lovely! Later, I learned that badgers do this to coax the worms out of the soil to eat them. Worms, apparently, do not carry sticks.

I started back to my lodgings, happy to have finally seen this wild animal.

As I rounded the trail for the final stretch, I saw another badger coming towards me on the path. Head down and as oblivious as me as I, initially, was to him. Like an old man being roused from his evening newspaper he started when he saw me. Surprised, he stopped. I stopped too. We locked eyes. I had no stick yet I had many, many, bones. What calculations we both made in those moments!

Minutes passed. Neither of us, it seemed, knew what do. Eventually, I decided to take the risk and I turned my head and looked off across the mountain. I waited, abandoning myself to my fate. Let him do whatever he chose….

When I looked back, he was gone.

It was—and this surprises me—the last badger I have seen.

I grow old, my circle contracts. Chicago is the farthest from Dublin that I will now reach. I dreamed last night I had returned to Dublin: the rope had been reeled in, my ambit narrowed. I will stand with a lit taper on Montpelier Hill: the cards fall from my hand; I wait for something to appear.

Liam Heneghan is professor of environmental science and studies at DePaul University. His book Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children’s Literature (University of Chicago Press, 2018) is available. Liam has been told it makes “excellent quarantine reading.”

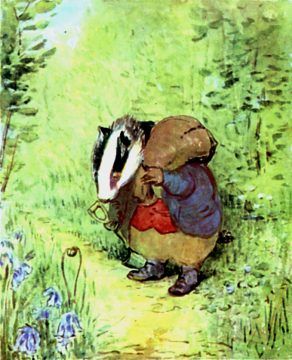

Image is Tommy Brock, as illustrated by Beatrix Potter in The Tale of Mr. Tod (Wikipedia)